|

Gerhard Richter: Panorama at Tate

Modern

by Anna Leung

|

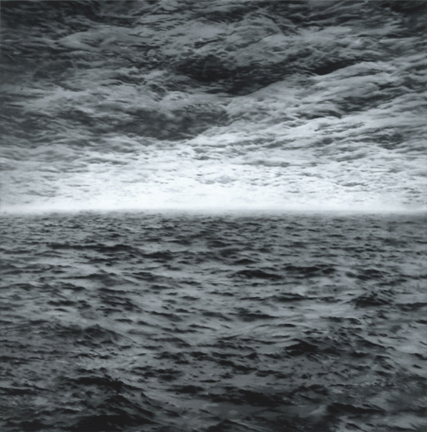

| Gerhard Richter, Seascape (Sea-Sea), 1970. |

Art the highest form of

hope!

We

need beauty in all its variations

From the late nineteen sixties and into

the seventies painting was in decline–some think it still is. Many painters, convinced that painting was an act of deception

that yielded only illusions, turned to performance, photography or film and video, representational modes that did not rely

on illusionistic devices. Gerhard Richter was one of the few who continued to paint while at the same time addressing this

problem of representation from within the oil-on-canvas tradition.

What was targeted during this period of transition was the assumption that paint had an idealist content and could,

as Abstract Expressionism intimated, convey metaphysical or transcendental meaning. After Abstract Expressionism, a more self

critical, reductionist, non-illusionistic and in some cases ironic mode of operation came to dominate painting practices.

While for the most part retaining painting’s rectangular format emphasis was placed on singular and material attributes

such as linear, colouristic or surface qualities (Stella, Ryman). In this way hierarchical and compositional effects were

reduced to virtual zero as was content or subject matter. As Stella succinctly put it ‘My painting is based on the fact

that only what can be seen there, is there….what you see is what you see.’. Cutting edge art across the board

was in the main objective, cool, cerebral, dispassionate and self-referential. Its philosophical ethos was positivism laced

with phenomenology and its goal was to repress all evidence of self-expression and thereby eliminate possibilities of ambiguity.

Thus during a period marked by great social and political displacement and unrest a kind of tautological game was being played

in which artists nevertheless saw themselves as resistant fighters against the status-quo. Richter risked being seen as conservative

since the consensus was that painting, especially of the oil on canvas variety, was intrinsically not avant-garde.

|

| Gerhard Richter, Table (Tisch), 1962. |

Gerhard Richter’s extremely productive

career needs to be seen against this shift in attitudes and expectations when pictorial references were no longer drawn directly

from the natural world but from an ever-growing nexus of information. Empirical data was being rapidly replaced by conceptual

data. From 1961 when he settled in West Germany Richter alternated between figuration and non-figuration treating a wide range

of subjects and employing a wide variety of means while not valuing one practice over another. As we shall see Richter is

equally adept at dealing with historical genres such as the nude, landscape, portraits and history painting as he is in investigating

colour and its absence in his monochromes and colour charts and in his densely layered, explosively coloured abstract canvases.

For Richter, Abstraction is as real as Realism is abstract, for what fascinates him is not the image per se or its absence

but appearance or semblance as our apprehension of appearance. Richter readily admits that it is inevitable that figurative

elements be seen in abstraction and denies any difference between what for him is a false polarity. That this panoply of styles

remains Richter’s consistent trademark throughout his long career can be seen as we wander through the rooms of this

vast exhibition. Each room displays figurative paintings, mostly from photographic imagery, side by side with abstract paintings.

There are two exceptions; the first is the room devoted to 18 October 1977, a cycle of fifteen photo-paintings based

on the deaths of the Baader-Meinhof terrorists in Stammheim high security prison, the second the Cage room of abstract paintings

that brings the exhibition to an close. Throughout the exhibition we see Richter appropriating mutually contradictory trends

associated with Hyperrealism, Minimalism and Conceptual Art while at the same time honing his craft as a painter to produce

some extraordinarily beautiful images. Impossible to categorise he demonstrates his determination to confront the crisis of

representation on one hand and that of Germany’s recent history on the other.

Gerhard

Richter was born in what was to become East Germany in1932 one year before Hitler took power. This meant that he lived through

two totalitarian regimes, making him sceptical of all political ideologies and on the whole intolerant to didactic art at

a time when there was much pressure on avant-gardist artists to be politically committed. Consequently he refuses to see his

art as overtly political unless we count his belief in the reconciliatory task of the aesthetic. The fact that his art education

was in the East meant that he was taught traditional drawing and painting skills but knew little of the modern movement, which

was regarded as bourgeois and therefore reprehensible to the Communist authorities. It was only after graduating as a mural

painter that he made his first trip to the West in 1959 travelling to Kassel to see Documenta II. Here he encountered the

work of Lucio Fontana and Jackson Pollock. Describing their innovations as ‘brazen,’ he had decided by the end

of the year to flee to the West, one year before the Berlin Wall was constructed dividing East from West. His coming over

to capitalist West Germany coincided with the rise of Pop Art, which released him from the obligation to actively choose specific

subject matter (which in the East had been imposed from above by the authorities). Source material was readily at hand in

news photos and magazine advertisements. Richter’s painting practice, however, was always complex: he seemed to embrace

tropes of high and low, the traumatic and the banal, romanticism and kitsch, and also showed divergent allegiances in his

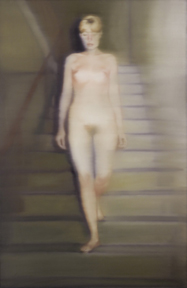

debts to Duchamp (Ema, Nude on a Staircase, his mirror/glass pieces), to Friedrich (romantic landscapes and

cloud and sea studies), to Vermeer (Reader 1994), to Ingres (Betty 1988) and to Beuys (The Chair)--in

short, to both the avant-garde and classical traditions. From the beginning he has reiterated that he knows nothing about

reality, only about its ‘translation’ into pictorial languages, painting’s sign systems, and that it was

precisely his doubts that linked him with classical painters.

|

| Gerhard Richter, Ema (nude descending a staircase), 1992. |

His first paintings were based on images taken

from newspapers and magazines. What he professed to be aiming for, in accordance with the artistic zeitgeist, were images

characterised by ‘no style, no composition, no judgement.’ Thus, armed with Duchampian indifference, his practice

was to project the image on the canvas and proceed to fill it in by hand with a brush. He later added amateur snapshots, including

his own, to his annotated collection of found images, insisting on their quality as pure images bereft of all intentionality.

Wedded to this aesthetic of indifference, it seems more than coincidental that he introduced into his practice subject matter

directly related to Germany’s recent Nazi past, images from his family album (one of the few possessions he brought

over from the East) that most artists would have chosen to keep concealed. Uncle Rudi for instance is a full sizes

portrait of his uncle in the uniform of the Wehrmacht--a going away photo, it turns out, as he was to die some months later.

What distinguishes this portrait and many others is the addition of Richter’s signature blur. Paint has been dragged

across the wet surface with a dry brush, signalling a whole variety of responses. Often interpreted as replicating an

out of focus snapshot, evoking speed, or signalling a temporal distancing by underlining the difference between the ‘now’

of the viewer and the ‘then’ of whatever was captured in the photograph, this flurry of soft or hard brush strokes

also signals a degree of moral and emotional ambiguity - despite the painter’s insistence on a lack of intentionality

on his part. Take his portrait of Aunt Marianne that depicts his maternal aunt cradling Richter as a none-too-happy

baby. A schizophrenic, she was sterilized and eventually starved to death by the Nazis. The blur of the brushstrokes bring

her and the baby together suggesting the very emotional attachment that Richter was initially keen to disavow. During an interview

in 1986 Richter confessed that this dispassionate stance of indifference was mere subterfuge and pretence on his part: “Content

definitely – though I may have denied this at one time, by saying that it had nothing to do with content, because it

was supposed to be about copying a photograph and giving a demonstration of indifference.” (1)

It was near to impossible, especially in post war Germany, to totally cleanse the motif of extraneous

or questionable subject matter. A series of landscapes that Richter started working on in 1968 would inevitably summon up

reflections on Germany’s recent history for it was all too easy to associate the majestic force of the mountains with

nationalistic strivings as exemplified in Leni Riefenstahl’s films Holy Mountain and Blue Light. Richter

does not ennoble The Alps but submits them to a process of disintegration or deconstruction so that, like his cityscapes which

carry conviction from afar, they become mere smudges and brush strokes as you approach them, challenging the expectation of

greater clarity the nearer we get to an image. The same is true of his cloud and seascapes, especially Sea-Sea which

seems initially to aspire to the sublime. One would think that this painting, especially, might suffer from a collapse of

romantic suspension of disbelief as we realise how the image has been collaged together; it is not the stormy sky we think

we see but an upside down image of the sea. Despite this trick/artifice, a residue of romanticism remains and is important

to our understanding of Richter. Faced with our longing to take pleasure in a primordial feeling of oneness with nature, Richter

repeatedly insists that nature is indifferent to our desires. However, the surge of unfulfilled desire to which this gives

rise can be viewed as an aspect of the Northern romantic tradition that attempts to picture what is unrepresentable and is

therefore not totally negative. It underpins Richter’s continued allegiance to Friedrich which comes to the fore in

his beautiful painting of Iceberg in Mist, 1982, that was inspired by Richter’s trip to Greenland in search of

a motif as strong as Friedrich’s The Sea of Ice, 1823.

|

| Gerhard Richter, Candle (Kerze), 1982. |

From the mid-1960s Richter embarked on a series

of abstract paintings based on colour and chose to explore this area in complementary ways. His colour charts replicate

those industrial or commercial colour samples that belong to the urban environment; the colors, confined to their separate

squares, debar the viewer from experiencing them in an expressionistic or naturalistic way. Every colour is a readymade and

there is no hierarchy since every colour is independent of every other colour. The series of Grey Paintings, on the

other hand, dealt with colourlessness but also blocked any inference of composition or internal relationships, being distinguished

from one another only by their textural surface. Artistically placing him in the Minimalist and Conceptualist camp, they were

the equivalent of fundamental painting, reductive painting pared down to its literal, rudimentary and materialist categories

that is closest in its objectives to Stella’s and Ryman’s self- problematising practices. However, Richter realised

that even the Grey Paintings could not entirely escape eliciting illusionistic or symbolic effects which inevitably turn painting

into something other than its material component. Indeed Richter confessed that while his Grey Paintings represented

a terminal point artistically on deeper level they may have been linked to his multiple unsuccessful attempts to paint the

concentration camps.

If as Richter admits the Grey Paintings represented a terminal

point, his Abstracts represented a new beginning, though he did not abandon all previous procedures. At first, his reliance

on source material through photographic enlargement continued as 128 Details from a Picture (Halifax), 1978, demonstrates,

as did his aim to minimise expressivity while fully acknowledging the painting medium. He was not trying to ally himself with

Abstract Expressionism’s search for transcendence any more than his colour charts allied him with Bauhaus colour theories.

If in his colour charts colours were isolated, in the new paintings colours were combined, and the introduction of the squeegee

made photographic source material or a starting image unnecessary. But making paintings remains a lengthy process. Richter

starts with a primed canvas covering it with layers of paint over days or weeks or months as readable elements, be they spatial

or structural, are eliminated. The squeegee creates areas of veiling that seem to reveal and conceal the underlying layers

and in so doing creates impressions of intense spatial complexity and of boundlessness which can be perceived as sudden flarings

up and extinctions of activity like fireworks or reflections and shadows in a swift stream. His aim is to create illusions,

the semblance of images, for as he says ‘there is no colour on canvas which means only itself and nothing more’

and presumably referring to Malevich adds that ‘otherwise the “black square” would only be a stupid coat

of paint.’ Richter’s Abstracts are not about creating intelligible symbols or iconic references but rather stand

as analogies of visual phenomena that continually make and unmake our experience of reality. The marks represent time, not

movement. Richter makes and unmakes his abstract paintings, describing them as ‘a highly planned kind of spontaneity’,

creation and destruction being part of the same process. Scrutinising them does not necessarily provide anything identifiable,

for they present us with momentary interpretations that promise meaning and then gainsay it. Despite the bold colours, this

phantasmagorical world is full of contradiction and indeterminacy, an indeterminacy and doubt that are reflected in his glass

pieces and notably in 18 October 1977.

|

| Gerhard Richter's Studio. Courtesy of the artist. |

From the 1980s onwards, Richter’s practice

tended towards the production of these abstract paintings, which now represent two thirds of his output. However, Richter

did not abandon genre painting. For Richter the two were different ways of achieving a similar aim and it was during this

period that he produced his series of Candles and Skulls and other genre compositions that linked Richter once more to the

Northern Romantic tradition. Among the best loved of these is his portrait of his teenage daughter Betty posing against one

of his Grey Paintings; that her back is towards us reminds us of Friedrich’s compositions. Richter was working concurrently

on his historical painting cycle of the Red Army Faction (RFA) that covered the arrest and death of the BaadeMeinhof Gang’s

leaders. The cycle opened with the Youth Portrait of Ulrike Meinhof, a journalist and mother of two daughters, the

painting of which may have had an added poignancy for Richter as he thought of his own daughter and her uncertain future.

The title 18 October 1977 records the day that begun with the diverting of a plane to Mogadishu by terrorists demanding

the release of the imprisoned leaders of the RFA, and ended with the deaths of three of them in the Stammheim prison: Baader

shot dead, Meinhof garrotted, and Esslin found hanged. Though the paintings are based on press photographs Richter transforms

them into powerful eidetic images that emulate film stills as they close up on a figure or face, his signature blurring deliberately

thwarts our attempts to interpret and make sense of the image while also adding to it a tragic dimension. The cycle conveys

an inescapable and overwhelming sense of sorrow and mourning so that it becomes a meditation on the death, possibly by suicide,

of the imprisoned terrorists. Titles such as Confrontation, Dead, Hanged, The Arrest, Man Shot

Done and Record Player (the record player in which Baader had concealed a gun) add to this effect, for rather than

personalising and particularising the event they remind us of the universality of the terrorists’ fate both as victims

and perpetrators of their ideologies.

Recent exhibitions have focused on one aspect of Richter’s

talents: portraits at the National Portrait Gallery and colour charts at the Serpentine, for instance. Tate Modern has chosen

the chronological rather than the thematic option, which is important for an artist who has from the start reiterated that

there is no difference between figuration and abstraction and that this is a false polarisation. Richter is fully aware of

painting’s vulnerability and of its fragile status in the contemporary art world but this is also his strength. He does

not resolve contradictions; indeed in his photo-pictures he makes the motif hard to see and circumvents a banal reading. The

same can be said of his abstracts. They constantly negate our assumptions through a systematic neither/nor procedure that

ultimately speaks for an open work rigorously structured but based on chance, in his own words ‘a highly planned kind

of spontaneity’ – hence his affiliation with the composer John Cage.

What

we have been given here is an opportunity to see how all these paintings, for all their differences, are centred on a core

of what cannot be said but which yet informs our sense of reality. The hope is always that something will emerge from this

sustained decision to continue painting since at this particular juncture in history, Richter tells us, it is only through

negation that art can express the ineffable. The one rider is in that despite picture making consisting of ‘a multitude

of Yes/No decisions’ there is ultimately a Yes that insists that despite obdurate reality, art and beauty furnish us

with a sort of hope, in Richter’s words, ‘the highest form of hope’ (2).

© Anna Leung

(1) Achim

Borchardt-Hume in Gerhard Richter Panorama, Tate Publishing 2011 (2) Benjamin Buchlow, An Interview with Gerhard Richter 2004

Anna Leung is a London-based artist and educator now semi-retired from teaching at Birkbeck College but taking occasional

informal groups to current art exhibitions.

|