|

Gerhard

Richter: Panorama

|

| Gerhard Richter, Forest (3) and Forest (4) 1990 Photo: Lucy Dawkins |

An

unbroken view: of the various meanings, translations, senses, metaphors of the word panorama, this is the one I’d choose

for this occasion.

Tate Modern is presenting us

with a full-scale retrospective of the German painter Gerhard Richter. The fourteen rooms resonate the multitude of complex

layerings on a body of works unraveling over a period of fifty years, from 1962 until today.

We should walk through these rooms to the rhythm of a sequence,

to allow continual discovery and exploration, not just of Richter’s works but also of the themes discussed by the most

recent history of art: painting/photography, randomness/craftsmanship, abstract/figurative.

The chronological aspect of this show combines perfectly with

the thematic structure of each room. At the end, the feeling, the impression, the emotions are fully represented by Richter’s own

words: “… painting is my profession, because it has always been the thing that interested me most.”

(Conversation between Gerhard Richter and Nicholas Serota, Spring 2011, catalogue)

|

| Gerhard Richter, Aunt Marianne (Tante Marianne), 1965 |

Born in Dresden in 1932, in 1962 he moves

across the borders to West Germany and bases himself in Dusseldorf. Since then, Richter starts using magazines, brochures,

catalogues, photographs, frames of films as sources for his painting and quite immediately the procedure of blurring appears,

something that, in time, will become a signature for his work and a metaphor for oblivion. As if time kept depositing insubstantial layers, veils on objects,

human beings, memories. “I blur to make everything equal, everything equally important and equally unimportant…”

Richter says. From the overpainted

photographs to the Grey paintings, the blurring technique transfers the same meaning of erosion that becomes evident in works

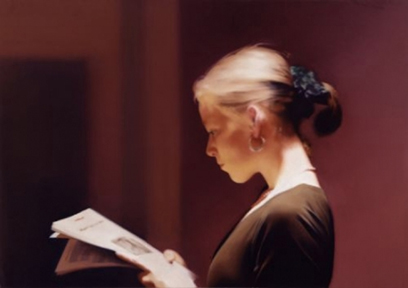

like Tisch (1962), Ferrari (1964), Ema (1966), Lesende (1994). Richter engages with history and tragic events in a unique way.

Pivotal moments punctuate, exist in the history of a Nation, when time goes by and shadows of oblivion descend on the consciousness

of every man. Richter has

the courage to assert and face moral challenge with the strength, the intensity of his work. He doesn’t want to judge.

It’s unique in the sense that he doesn’t want to invoke an ideology or a political point of view but it’s

a kind of moral imperative for him and for us, the viewers. This is true for Tante Marianne (1965), Herr Heyde (1965), Uncle Rudi

(2000), where family history and History intertwine and combine and for the works related to the aerial bombardments during

WWII and also for 18 Oktober 1977 (1988), a group of works on the tragic final days of the Baader-Meinhof, and for

September (2005) on 9/11.

|

|

|

| Gerhard Richter, Reader, 1994. Courtesy of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. |

The pictorial effect of blurring

universalizes the figurative reference to a moment in history, while overcoming the fortuitous effect to present itself as

a moral imperative

Some rooms of this exhibition just resonate of reflection and

silence. The work with glass resumes many themes and spreads from transparence and reflection as in 4 Glasscheiben

(1967), 11 Scheiben (2004) to blurring and dissolution as in Doppelglasscheibe (1977), 6 Scheiben in einem

Rack (2002-11) where an opaque surface absorbs light.

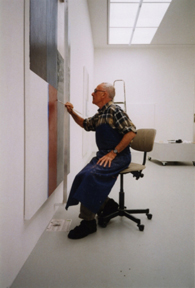

From

the early Eighties, Richter starts painting with the squeegee, a device that is wiped across the canvas to remove and spread

the pigment, unintentionally creating, revealing abstraction. But curiously on these canvases a kind of figuration strikes

back.

It is through this process that takes form the considerable corpus of works in which abstraction

and figuration find a new level of equilibrium, a unique way of blurring the opposition.

|

| Gerhard Richter at work. Courtesy of the Artist. |

This exhibition, in a few rooms, underlines the freedom and the determination

of Richter’s inner persona. I think that over the years

we tended to read the richness of his works in fragments, under a partial point of view. The strong point, the merit of this

exhibition is to allow a gaze over Richter’s oeuvre and from a perspective of global view. And here a chance of surprising emerges. Although Richter uses different techniques

and ways of approaching the medium, the painting in itself remains the constant factor.

Floriana Piqué is an art critic and independent curator. She

lives and works in London.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|