|

In his book Gerhard

Richter: A Life in Painting (2002), Dietmar Elger touches briefly on Richter’s

visit to the Duchamp retrospective at the Museum Haus Lange in Krefeld in 1965. The show, Elgar recounts, “made

a strong

impression . . . triggering shifts in [Richter’s] thinking—some large, some

subtle—that would affect him long into the future.” The gallery devoted to Richter at the High

Museum of Art in Atlanta wonderfully brings to light the lasting and

multifaceted impact of Duchamp on Richter’s art. A centerpiece of the museum’s impressive

contemporary collection, the Richter room offers a remarkable sampling of

Richter’s later output (the earliest of the works is from 1988): three

paintings (two abstracts and one photo-based portrait) and two large glass

installations. Taken together, the works

offer a provocative illustration of Richter’s continued grappling with the

Duchampian readymade and its implications for pictorial art.

The idea of the readymade

was, of course, introduced into

art history in the early-twentieth century with Duchamp’s practice of

designating as works of art commonplace, mass produced objects such as a bottle

rack, a snow shovel, and, most notoriously, a urinal (Fountain, 1917). At a talk he gave at New York’s

Museum of

Modern Art in 1961, Duchamp outlined briefly some of the ideas that lay behind

the readymade. First, the choice of an

object to be designated a readymade was, Duchamp said, “never dictated by

aesthetic delectation.” “This choice,”

he went on to say, was instead “based on a reaction of visual indifference with

at the same time a total absence of good or bad taste . . . in fact, complete

anesthesia.” Equally important, Duchamp

continued, was the readymade’s “lack of uniqueness.” In his essay entitled “Painting: The Task

of

Mourning,” reprinted in his book Painting

as Model (1990), Yve-Alain Bois argues that Duchamp’s “readymades were not

only a negation of painting and a demonstration of the always-already

mechanical nature of painting. They also

demonstrated that within our culture the work of art is a fetish that must

abolish all pretense to use value.”

Gerhard Richter Abstract Painting (Abstraktes Bild), 1997. Courtesy of the High Museum and the artist.

That Richter understood

the readymade’s implications for

painting in a way similar to Bois’s formulation is suggested by his almost

immediate artistic response to the Duchamp retrospective, the painting Toilet Roll (Klorolle) (1965).

From a

newspaper photograph of a toilet paper roll, Richter painted a deadpan grisaille reproduction (the source

material is included in Atlas, Richter’s

compendium of found photos, snapshots, newspaper clippings, and sketches). Clearly evoking Fountain, Duchamp’s

most notorious readymade, this early painting

heralds Richter’s career-long fascination with the anonymous, mass-produced,

documentary nature of the photograph, which pushes it in the direction of the

readymade. In Pictures of Nothing (2006), Kirk Varnedoe discusses the transformations

of the aesthetic of the readymade by Richter’s almost exact contemporary, the

American Jasper Johns (b. 1930). Varnedoe

writes that in his flags and targets Johns “transmutes Duchamps’s idea of the

readymade into something new. It is a

way of making art rather than a way of not

making it.” While Richter rejects what

he writes off as Johns’s fidelity “to a culture of painting that had to do with

Cézanne,” he similarly explores the implications of the Duchampian readymade

for pictorial art.

Richter’s reputation

rests primarily on the paintings that,

like Toilet Roll, uncannily resemble

their photographic sources. His comments on photography suggest that

Richter’s turn to painting from photographs stems from his understanding of the

photograph as a kind of readymade. Striking

a rather Duchampian note, a notebook entry from 1964 reads: “Painting from a

photograph seemed to me the most moronic and inartistic thing that anyone could

do.” “The fascination of a photograph,” he adds a page later, “is not in its

eccentric composition but in what it has to say: its information content.” That same year, he writes again, “That

is why

I like the ‘non-composed’ photograph. It

does not try to do anything but report on a fact.” Richter seems to intuit what Duchamp later

stressed as one of the key ingredients of the readymade: “just this matter of

timing, this snapshot effect.” In her

influential essay “Notes on the Index” (1976) [reprinted in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other

Modernist Myths (1986)], Rosalind Krauss elaborates on the parallels

between the photograph and the readymade, arguing that both are “about the

physical transposition of an object from the continuum of reality into the

fixed condition of the art-image by a moment of isolation, or selection.” Richter’s repeated insistence

that he likes

photographs because they have “no style, no composition, no judgment” would

seem to suggest that his interest in photography devolves on an idea of the

photograph as readymade, on photography’s ability to isolate an object with a

minimum of manipulation, modification, or alteration. Richter appears to regard the camera in a way

similar to that of contemporaries such as Warhol, Ed Ruscha, or Douglas

Huebler—as a dumb recording device.

Gerhard Richter, (7991) Lesende (The Reader), 1994. Courtesy of

the High Museum and the artist.

Over thirty years separate

Richter’s first paintings from photographs from the works in the High’s collection.

Nevertheless, as these works

make clear, Richter’s dialogue with Duchamp continues in subtle and provocative

ways. The collection contains one

photo-based painting, Lesende

(1994). Unlike many of Richter’s early

paintings from photographs, Lesende originates

not with a “found” photograph but with one that Richter took himself, a

snapshot of his wife, Sabine, reading. (Again,

the source photograph can be found in Atlas). The

painting’s origin in a photograph introduces into the painting first Richter’s

rejection of the idea of the painting surface as “window” onto the world. As Richter had written as early

as 1962, “The

idea that art copies nature is a fatal misconception. Art has always operated against nature and

for reason.” And, while the photograph

from which Richter paints is not a “found” object, it does approach the idea of

the “snapshot as readymade.” The model

in the photograph is not posed, but presumably caught unawares as she reads

from the German weekly news magazine Der

Spiegel.

Lesende provocatively

engages photography, the readymade, and painting--both abstract and Old Master. Richter’s source photograph brings

an element

of contingency to the painting, as the “sitter” is turned away from the camera,

absorbed in her reading. Because Richter

eliminates almost all detail from the painting, the figure is removed from any

kind of context. Pushing the painting in

the direction of abstraction, Richter focuses on the fields of black, brown,

and red that play off the white of the reader’s page, blonde hair, and

whiteness of her neck. In an entry from

his notebooks from the mid-sixties, Richter jotted down: “The photograph has an

abstraction of its own, which is not easy to see through.” Richter’s famous “blurring” of the

painting

surface brushes up against photography’s abstractions at the same time that it

evokes Old Master paining, specifically Vermeer of Delft. In his

book on Richter, Elger notes that Lesende’s

“sister” work, Lesende (CR: 804), a

similar painting with Sabine reading in profile (currently in the collection of

the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art), “is a clear attempt to bring Jan

Vermeer’s A Girl Reading a Letter by an

Open Window (ca. 1659) into the twentieth century.” That Richter’s model reads Der Spiegel, a

mass produced magazine,

brings yet another layer to a deceptively simple painting, superimposing

representational systems: painting on photography, and mass media on painting. Although the perspectival system of

Renaissance painting treated the picture plane as a window through which to see

the world receding into the distance, there is an equally strong historical

discourse that posits the picture plane as a mirror “held . . . up

to nature.” The impeccably smooth, glass-like finish of the painting combined

with the allusion to mirrors in the title of the journal the model reads

suggest humorously Richter’s turn away from the idea of painting as a window. The

painting mirrors the surface of the reader’s reality much as the magazine

promises to mirror the world for her.

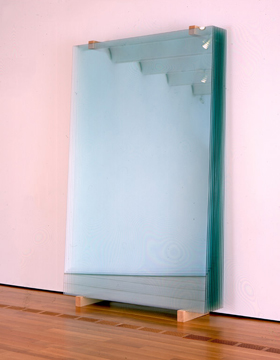

Gerhard Richter, 7 Standing Panes, 2002.

Courtesy of the High Museum and the artist.

Richter takes on this

dichotomy of painting as window or

mirror more directly in the glass installations, which directly engage

Duchamp’s The Large Glass

(1915-1923). Duchamp’s Large Glass is notoriously complex and

his notes to it arcane and enigmatic. Echoing

the irritation of his one-time teacher Joseph Beuys who famously quipped that “the

silence of Marcel Duchamp is overrated,” Richter has registered more than once

his impatience with what he calls Duchamp’s “mystery mongering.” But significantly for Richter, Duchamp’s

Glass contains mirrored surfaces and

shapes transferred from photographic imprints.

In an article entitled “Where’s Poppa?,” included in the collection

edited by Thierry De Duve entitled The

Definitively Unfinished Marcel Duchamp (1991), Rosalind Krauss has pointed

out that Duchamp had originally intended that the upper half of the Glass be coated with a bromide emulsion that

would have suggested a photographic plate. Richter had begun to address Duchamp’s Glass directly as early

as 1967 with his

4 Panes of Glass which, Elger tells

us, Richter had “understood as a transparent and in a figurative sense, clear

antithesis to Duchamp’s mystical Large

Glass.”

Richter’s glass

constructions at the High are stunningly

simple in execution. 11 Panes (2003) consists of just what

the title indicates, 11 panes of glass lightly glazed, stacked one upon

another. Mounted on the wall like a

painting, the hazy, mirror-like surface of the panes reflects the spectator’s

image back at him or her. This not-quite-transparent-not-quite

opaque quality of the panes makes them, as Richter said of his earlier colored

mirrors which the panes resemble, “a kind of cross between a monochrome

painting and a mirror.” The panes throw

spectators’ airy, blurring reflections back at them, making the viewer appear

almost like one of Richter’s photo-paintings.

Gerhard

Richter, 11Scheiben (8863) (11Panes), 2003. Courtesy of the High Museum and the artist.

Comprised of 7 free-standing

panes of glass in a steel

construction, 7 Standing Panes (2002)

similarly evokes Duchamp’s Large Glass.

Once again, the reflective surfaces of

the piece throw our image back at us. As

we circle what appears to be a fairly simple piece, the shiny surfaces create

an ever changing, diffuse and muted reflection of our image and space. At times we catch a momentary glimpse of our

image multiplied in regress, recalling the famous mise en abyme image of Charles Foster Kane passing before a hall

of

mirrors toward the end of Welles’s Citizen

Kane (1941). As early as 1965,

Richter had written in his notebooks: “All that interests me is the grey areas,

the passages and tonal sequences, the pictorial spaces, overlaps and

interlocking. If I had any way of

abandoning the object as the bearer of this structure, I would immediately

start painting abstracts.” These recent

ripostes to Duchamp’s Glass execute

wonderfully just these “passages and tonal sequences,” the overlaps and

interlockings of our continuous shifting reflections. Rejecting what he calls the “pseudo-complexity”

or “manufactured mystery” of Duchamp’s Glass

(and its notoriously abstruse “notes”), Richter’s glass constructions operate,

as he has said, “immediately and directly,” outwardly unpretentious yet utterly

captivating.

As Richter suggests,

these large glass constructions are

related to the most radically abstract painterly tradition of the

monochrome. While Richter’s photo-based

paintings have always engaged ideas of abstraction, he did not begin to make

strictly abstract paintings until about the early seventies. When he did so, art critics found themselves

pressed to reconcile these abstractions with Richter’s photo-based

paintings. In a notebook entry from

1982, Richter writes, “Everything made since Duchamp has been readymade, even

when hand-painted,” ostensibly alluding to Duchamp’s observation that since the

widespread adoption of tubes of paint, all painting is to some degree

readymade. Might we view Richter’s

abstracts, then, through the lens of the readymade? If we accept that Richter views photographs as

readymades, then we might say of his abstract paintings what Bois said of

Robert Ryman’s paintings—that they get ”closer and closer to the condition of

the photograph or readymade.” Richter

himself suggests as much. In a 1972

interview with Rolf Schön, Richter says: “It [the photograph] had no style, no

composition, no judgment. . . And if I disregard the assumption that a

photograph is a piece of paper exposed to light, then I am practicing

photography by other means: I’m not producing paintings that remind you of a

photograph but producing photographs.

And, seen in this way, those of my paintings that have no photographic

source (the abstracts, etc.) are also photographs.”

The large, mostly grey

Abstract

Painting (2011) from the High’s Richter collection evokes Richter’s earlier

and quick remarkable series of monochromes Eight

Grey from 1975. But unlike those

earlier paintings, this one contains touches of brilliant color. Wonderful greens and deep reds lurk beneath

the mottled layers of grey paint that makes the canvas look almost like a found

object, like a weathered piece of sheet metal.

The even larger painting, Blau

(1988) (currently on loan to the High from a private collection), which hangs

right across from this painting consists of rich layers of paint in various

colors. A swath of blue paint sweeps

downward, diagonally, from about the mid-section. A white line running down almost from the top

of the canvas to the bottom right third of the canvas invokes perhaps the

famous “zips” of Barnett Newman, an artist that Richter speaks quite highly of. Splotches of red,

orange, yellow, and brown

cover the left side. The gestural look

of the painting is, however, something of an illusion. Close inspection reveals that the surface is

gouged and scratched. The dappled colors result from Richter’s use of a tool

such as a metal ruler to scrape and graze away layers of paint, leaving a

canvas that looks a bit like peeling wallpaper (perhaps an allusion to Harold

Rosenberg’s dismissal of second generation Ab Ex painting as “apocalyptic

wallpaper”) or metaphorically the layers of Troy. Perhaps Richter’s unearthing of layers of

paint alludes to Jackson Pollock’s practice, in paintings such as Ocean Greyness (1953), of leaving small

splotches that reveal the painting’s initial paint layers. Richter’s “excavation” here of his

own layers

of paint might even be a nod in the direction of de Kooning’s masterpiece Excavation (1950). But Richter’s

scratches and abrasions pull

abstraction away from the personal expression of a Pollock or a de Kooning,

pushing toward the anti-expressive factitiousness that Richter associates with

the photograph.

The works in the High’s

Richter room intrigue and astonish,

revealing, among many other pleasures Richter’s deep and inspired engagement

with another modern master, Marcel Duchamp.

Robert Stalker

is an Atlanta-based freelance

arts writer.

|