|

|

| Installation View, Frida and Diego, High Museum of Art, Atlanta © Virginie Kippelen 2013. |

Dr. Elliott King is an Assistant Professor of Art History and Washington and Lee University (please visit his website at spiralspecs.com). His research focuses

on Surrealist art and thought with an emphasis on the post-war art and writing of Salvador Dalí. In 2010, Dr. King was Guest

Curator of the critically acclaimed exhibition, Dalí: The Late Work, at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, Georgia

(catalogue published by Yale University Press, 2010). He has returned to the High Museum as the Guest Curator of Frida & Diego: Passion, Politics, and Painting at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta from February 14, 2013 – May 12, 2013. He and TAS Editor-in-Chief Deanna

Sirlin exchanged thoughts by email.

Deanna Sirlin: Do you think Diego and Frida influenced each other in the studio?

Elliot King:

Curating this exhibition, I heard time and time again that Diego influenced Frida but not vice versa. I understand why one

would think that looking at the work, but I’m not convinced it’s so one-sided. In the exhibit, we have Frida’s

1929 painting, The Bus, and it’s clear in that painting that she had already begun to incorporate elements of Diego’s

social realism just a year after they met. You specifically ask about their interactions in the studio: Each was often present

while the other was working, and I can easily imagine Diego offering suggestions while Frida painted. To be honest, she probably

took most of them; he was, after all, twenty years older and one of the most famous artists in Mexico when they met. His style

was established by the late-1920s whereas hers was only blossoming, and naturally she looked up to Diego and probably acted

on a lot of his advice. That’s not to say she was only derivative, of course, but his influence was very strong. I actually

don’t imagine Frida giving Diego artistic guidance in the same way. I’m not sure he would have taken it. Still,

I cannot believe a couple would be together for twenty-five years and the influence would go in only one direction. They shared

life circumstances, and he was constantly around her paintings; there has to have been some effect on his paintings as well

as hers.

DS: In retrospect who is the more important artist, in the sense of influencing

the next generation of artists?

EK: Perhaps it’s telling that when the Mexico

City-based design consultancy THiNC (Ignacio Cadena and Héctor Esrawe) came aboard to design the show’s reading rooms,

they pulled their inspiration from specifically Frida’s diaries and imagery from her paintings, not Diego’s; there’s

just something about Frida that seems to connect with people today – much more so than Diego.

With that

in mind, my first reaction would be to speculate that Frida will hold the greater influence on the next generation of artists.

I will probably get feedback to the contrary, but that’s my opinion. It’s partially due to accessibility: Diego’s

public murals are basically limited to San Francisco, Detroit, and Mexico City, so it’s much harder to get a sense of

his work without going to those cities and seeing his murals in person. Today, we’re more likely to look at art on a

screen than go on a pilgrimage to see a wall mural, and frankly Diego’s frescoes need to be seen in person to be really

appreciated. Even his easel paintings – particularly his Cubist paintings – are much different in person and really

don’t translate well through electronic media. By contrast, Frida’s paintings are more easily disseminated and

digested. They have a smooth finish, so brushstrokes aren’t lost in reproduction. Greenberg would have said that’s

a bad thing, obviously, but I think it helps account for her present-day iconic status and the impact I suspect her work will

have on contemporary artists.

Frida also strikes me as more connected to contemporary

theory than Diego. She has been adopted by feminist scholarship and LGBT studies, whereas Diego’s paintings seem to

me to be more intrinsically rooted to their particular time and political circumstance; one might say his works are more historical

and hers more timeless. Frida executed her share of hammers and sickles as well, but most of those paintings are in the collection

of the Casa Azúl and consequently can’t be lent to outside exhibitions, meaning they’re much less well-known than

her other self-portraits. Again it becomes an issue of accessibility.

I don’t want to

discount Diego. I’m purely speculating about the near-future of contemporary art given present-day concerns, which tend

to favor ready dissemination and marketability over explicit social and political narrative. Perhaps future critics will look

back on the twentieth century and recognize Diego as one of the singular great masters. Certainly one of his legacies should

be that he was one of the first to bridge art and political activism. And importantly, he was doing it in a public space.

The idea of creating art that was accessible to people outside the museum – of democratizing art by bringing it out

of gallery, to the people – influenced many late twentieth-century artists who defied traditional exhibition spaces

to ‘take to the streets’. I’m not just speaking of the 1960s Chicano Mural Movement, which looked consciously

to ‘los tres grandes’ – Diego, David Alfaro Siquieros, and José Clemente Orozco; I think one could make

convincing case to connect Diego’s Mexican muralism with elements of contemporary street art. Especially when it’s

blown up to the level of international politics…say, Banksy’s public murals on Israel’s West Bank barrier

– I actually think there’s a lot of Diego Rivera in that work.

Diego Rivera (Mexican, 1886

– 1957), El Sueño (La Noche De Los Pobres) (Sleep (The Night of the Poor)), 1932, lithograph on paper, Collection

of Museo Dolores Olmedo, Xochimilco, Mexico. © 2012 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D. F.

/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

DS: Was Frida a Surrealist? How was she different from other surrealists?

EK:

I oscillate on this question day-to-day. To summarize, in 1938, the Surrealists’ leader and chief theorist, André Breton,

visited Mexico and ‘discovered’ Frida’s painting during a visit with Leon Trotksy, who was then living with

Frida and Diego. Seeing her emotional self-portraits, he proclaimed her as a Surrealist ‘despite the fact that [her

paintings] had been conceived without any prior knowledge whatsoever of the ideas motivating the activities of my friends

and myself.’ Breton then organized Frida’s first solo exhibit in New York at the Julien Levy Gallery, a well known

gallery for Surrealist art. For her part, Frida exhibited as a Surrealist, and both she and Diego were featured in the 1940

International Surrealism Exhibit in Mexico City. Only later did she reject the Surrealist label, saying that Surrealism was

about dreams whereas her work depicted her own reality.

Frida’s

disavowal of Surrealism based on dream imagery isn’t that clear. Surrealism is rightly associated with dreams, but that’s

because Surrealist painting is more about process than product. To be Surrealist, the process has to be one that delves into

the subconscious – ‘free of aesthetic and moral considerations’, as Breton wrote in the Surrealist Manifesto

of 1924. Dreams were one area – for a long time, the main area – the Surrealists explored to tap into the subconscious,

but certainly by 1938 it wasn’t the only style of Surrealist painting. The more telling issue, really, is to what

extent Frida’s process was Surrealist. This may be overly pedantic, but it’s an interesting question. Clearly

she wasn’t deliberately aiming for the Freudian subconscious; her style was already rooted in Mexican indigenous art

well before she met Breton, and it was only to an outsider like Breton that her fantastic imagery could have been feasibly

identified as Surrealistic. This would be the argument that she wasn’t really a Surrealist and that Breton ‘mis-labelled’

her. On the other hand, Breton had already identified a number of artists as Surrealist in spirit – Picasso among them

– and he may well have recognized a ‘savage eye’ in Frida’s work, too. I suppose keep going back to

Breton’s definition of Surrealism as ‘Pure psychic automatism, by which it is proposed to express – verbally,

in writing or by any other means – the true functioning of thought. The dictation of thought, in the absence of all

control exercised by reason, and outside all aesthetic or moral considerations.’ Here he doesn’t explicitly say

a Surrealist has to be aiming to tap the subconscious – only that he or she must endeavour to express ‘the true

functioning of thought’ without any moral or aesthetic filter. If that’s our bar, I think we can say that Frida

was expressing her own personal thoughts in the most raw, direct form of which she was capable. She once wrote, ‘I never

knew I was a Surrealist until André Breton came to Mexico and told me I was. The only thing I know is that I paint because

I need to, and I paint always whatever passes through my head, without any other consideration.’ That process –

painting whatever passes through one’s head without consideration – is the definition of Surrealism, even if she

didn’t think of herself as part of the group.

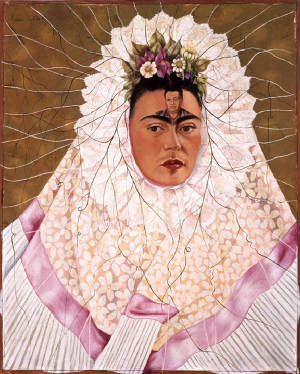

Frida Kahlo (Mexican, 1907–1954), Autorretrato como Tehuana (Diego en mi Pensamiento)

(Self-Portrait as Tehuana (Diego in My Thoughts)), 1943, oil on masonite, The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of

Mexican Art. © 2012 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D. F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS),

New York.

DS: Do you

think there was an aspect of performance to the way Frida and Diego dressed and behaved as “artists”?

EK:

Both Frida and Diego were acutely aware of their public images. The earliest Diego work we have in the show is a self-portrait

from 1907, and even at that young age, he’s playing a part – a young artist with a beer, smoking a pipe in a darkly

lit corner of a bar. Neither Frida nor Diego could have been in the public eye as much as they were and be ignorant of their

presentation, which I think we can certainly call ‘performance’. I’m thinking mainly of the way Frida dressed,

by the way. In terms of behavior, I’m not sure they were behaving in a particularly ‘artistic’ manner, to

be honest. If we’re talking about the various extra-marital affairs each of them had, for instance, I wouldn’t

call that behaving as an artist, necessarily, and would find it more intriguing to connect their open marriage to Karl Marx’s

disapproval of monogamy. It seems like sort of a cop out to say they were just ‘behaving like artists’.

DS:

Surrealism is part of Modernism; however Modernism is a movement of the past that has ended. Surrealism is still part of contemporary

art. Can you explain why this happened?

EK: I’m not sure ‘modernism is a movement

of the past that has ended,’ even if one were to take the position that contemporary art is in an age of post-modernism

(or post-post-modernism?). Certain ideas of modernism are deeply engrained, even when contemporary art and theory seeks to

overturn them. I’m also hesitant to identify Surrealism as ‘part of contemporary art’ without nuance: Surrealism

as a movement is still very much alive (despite having been declared ‘dead’ countless times over the decades),

but while there are Surrealist groups and, within those, Surrealist artists working today, most of Surrealism’s influence

on contemporary art is historical and conceptual. No major contemporary artists would describe themselves as Surrealists,

just as I suspect no major artists would call themselves modernists. Yet there are both Surrealists and what we might call

‘modernists’ out there. If the question becomes, then, why Surrealism continues to hold an influence today more

so than, say, AbEx, I’d offer that it has to do with the qualities that made Surrealism distinct even in the 1920s and

1930s – its interest in popular culture, exploration of multiple viewpoints and perspectives undermining fixed signifiers,

privileging of the viewer, and interest in spectator experience. Surrealism simply has more in common conceptually with postmodernism.

DS:

Do we have a parallel of a couple in the public eye like Diego and Frida?

EK: I don’t

know who it would be. Some people have compared them to Georgia O'Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz, Christo and Jeanne-Claude,

or Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen, but Frida and Diego were different from all these. They weren’t collaborators

in the sense of Christo and Jeanne-Claude or Oldenburg and van Bruggen. They were also much more in the public eye than these

couples – so much so that one could try comparing them instead to contemporary celebrities, but that wouldn’t

do justice to their political activism. Maybe if Bono and Ali Hewson had a more tumultuous marriage…? I’m just

going to have to go with no.

Frida Kahlo (Mexican, 1907–1954),

El Abrazo De Amor De El Universo, La Tierra (México), Diego, Yo Y El Señor Xólotl (The Love Embrace of the Universe, the

Land (Mexico), Diego, Me, and Señor Xólotl), 1949, oil on masonite, The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection of Mexican

Art. © 2012 Banco de México Diego Rivera Frida Kahlo Museums Trust, Mexico, D. F. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

DS: Why does our culture like this kind of drama for its artists?

EK: Our culture likes drama in general, doesn’t it? Perhaps expectations are different

for artists because there is the lingering stereotype of an ‘artistic temperament’, so some eccentricity is expected.

Honestly, however, our exhibit doesn’t delve that much into their personal dramas. Maybe some visitors will be disappointed

by that, but I don’t think it’s anywhere near the most important thing about Frida’s and Diego’s relationship.

The fact that Diego had an affair with Frida’s sister is important for Frida’s painting, Self-Portrait with Cropped

Hair, for example, but that story is tucked away into extended wall label and not emblazoned across a wall text or even in

the catalogue. That’s not to avoid it, but that story has been told. I was less interested in what tore them apart than

what brought them together.

DS: This show is a bit like a biography with photos of both the artists as part of the exhibition. Why did you decided

to include so many photos?

EK: It’s sort of biographical,

I suppose, though the photographs serve an important curatorial point. Working with the High’s Curator of Photography,

Brett Abbott, we were very conscientious to present the photos as artworks and not simply didactic elements to further our

story. That’s one of the reasons that they’re presented together in the last gallery and not spread throughout

the exhibit. The idea came from one of my visits to the Museo Dolores Olmedo in Mexico City: In addition to all of their impressive

galleries of paintings, the Olmedo Museum has a gallery of photographs. I was with a group from the High, and everyone loved

the photos; they’re just captivating. I think that after seeing the artists through their paintings, it’s especially

exciting to then see them ‘as people’ – interacting with each other, creating art together, marching together

in a May Day rally, etc. For us, it’s sort of the exhibit’s ‘take away’. Some visitors may enter the

exhibit thinking about Frida and Diego as very different types of artists, but after seeing their work together and thinking

about their mutual influences and context, the photographs really drive home the exhibition’s argument that they were

very important not only as singular artists but also as a couple. DS: Since Frida was in a lot of pain most

of the time, how do you think it affected Diego’s art?

EK:

I don’t know if her pain necessarily impacted Diego’s art beyond the emotional trial of seeing someone you love

in constant pain. I will say that both were going through certain painful life circumstances that manifest in their respective

artworks. For example, one of Frida’s most powerful paintings is Henry Ford Hospital, painted in 1932. The painting

refers to Frida’s second miscarriage, suffered in Detroit during the time that Diego was painting his Detroit Industry

frescoes at the Detroit Institute of Arts. Is one to think that this tragedy impacted only Frida and not Diego? It’s

interesting to consider the Detroit Industry frescoes with this event in mind, as the outdated fender-stamping press in one

of the main murals has been identified as referencing the Aztec goddess of creation, Coatlicue. Coatlicue is also the patron

of women who die in childbirth, which is to say that I’m sure Frida’s miscarriage was very much occupying Diego

during his work in Detroit.

DS:

Has curating this exhibition changed the way you think about the works or the artists?

EK: Absolutely. When I began this project, I subscribed to many

stereotypes about Frida and Diego. I thought of Diego as the more political of the two and tended to frame Frida in a much

more submissive role, as one who was generally reacting to Diego but not really asserting herself. The truth is much more

interesting – that Frida considered herself a better Marxist than Diego, and both artists were engaged in an open relationship;

after they divorced, they remarried very much on Frida’s conditions. I now see her self-portraits as strong and resolute.

I’m also more intrigued now with Diego’s work, which I thought drew chiefly from Mexican imagery; now I see much

more European influence in Diego’s paintings. That’s one of the reasons Frida & Diego is an important exhibition:

It confronts stereotypes about both artists and leads visitors to think differently about them and their work, individually

and as a couple.

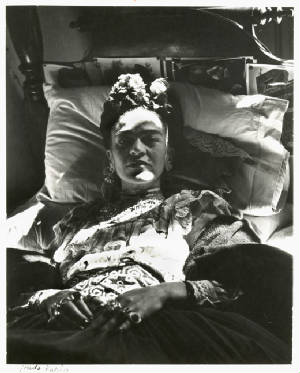

Bernice Kolko (American, 1904

– 1970), Frida Kahlo, 1950, gelatin silver print. High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase, 1977.35

|

Deanna Sirlin

Photo:Evie Saleh |

Deanna Sirlin is an artist and writer living outside of Atlanta, GA.

Her forthcoming book She's Got What It Takes: Contemporary American Women Artists in Dialogue will be published

by Charta Art Books.

|