|

Alighiero Boetti:

Game Plan at Tate Modern

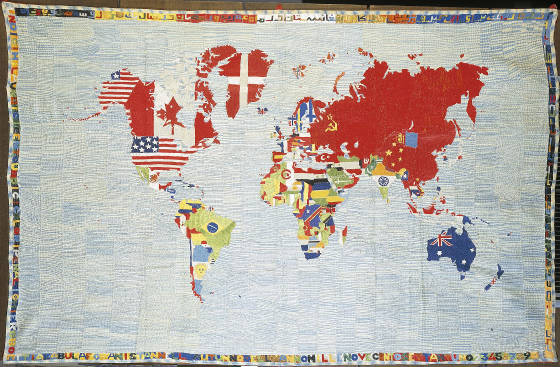

Alighiero Boetti, Mappa, 1971-1972. Private collection. © Alighiero Boetti Estate by DACS / SIAE, 2012.

The title of the exhibition gives us a clue to interpreting the work and the

life of an artist whose strength is even more actual today than ever. This retrospective shows the artistic production of Alighiero Boetti both in

a diachronic way from the Mid-Sixties--his first one-person exhibition was in 1967 at the Christian Stein Gallery in Turin,

and in thematic rooms, until the Mid-Nineties.

The first room at Tate Modern is permeated by the character of Turin –

where Boetti was born in 1940 – as an industrial city. Catasta (Stack), 1967, a number of Eternit tubes, is a composition designing

in the space a precise geometrical volume, while Rotolo di cartone undulate 2 (Roll of Corrugated Cardboard 2), 1986

(first version 1966), is an artistic subversion of packaging material essential for any industrial activity.

He came into prominence

with the movement of Arte Povera, a group of artists with strong personalities mainly based in Turin, and he shared

with them artistic, poetic, human solidarity. In Manifesto, 1967 the artist listed 15 names of fellow artists sided

by secret, hermetic codes, in Citta’ di Torino (City of Turin), 1968 – a map of the city – he marked

the streets where some artists lived.

Alighiero Boetti, Io che prendo il sole a Toriino il 19 gennaio 1969. © Alighiero Boetti Estate by DACS / SIAE, 2012, courtesy Fondazione Alighiero e Boetti. Private Collection.

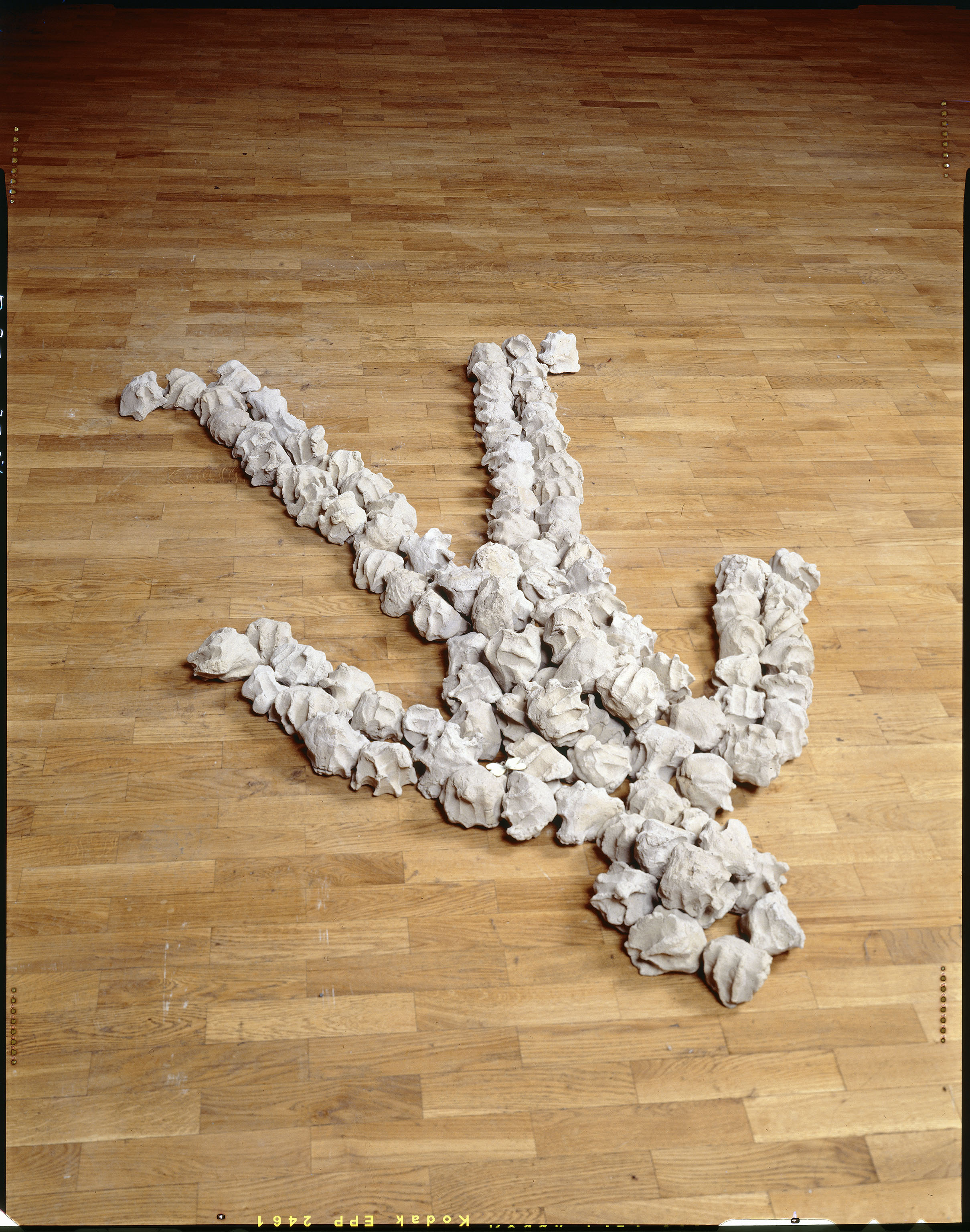

In the second room there are

works exhibited in the one-person show at the Sperone Gallery in Turin, spring 1969 that evidence his withdrawal from Arte

Povera: Io che prendo il sole a Torino il 19 gennaio 1969 (Me Sunbathing in Turin January 19, 1969), 1969, which

consists of clumps of cement arranged in the shape of the body of the artist, a yellow butterfly on the chest, and Niente

da vedere niente da nascondere (Nothing to See Nothing to Hide), 1969, a square glass window leaning against a wall instead

of against the world, provoke doubts and revert all the certainties of representation.

These works mark a turning point towards conceptual research. Exploring images of himself, Boetti expands the possibilities of twinning and

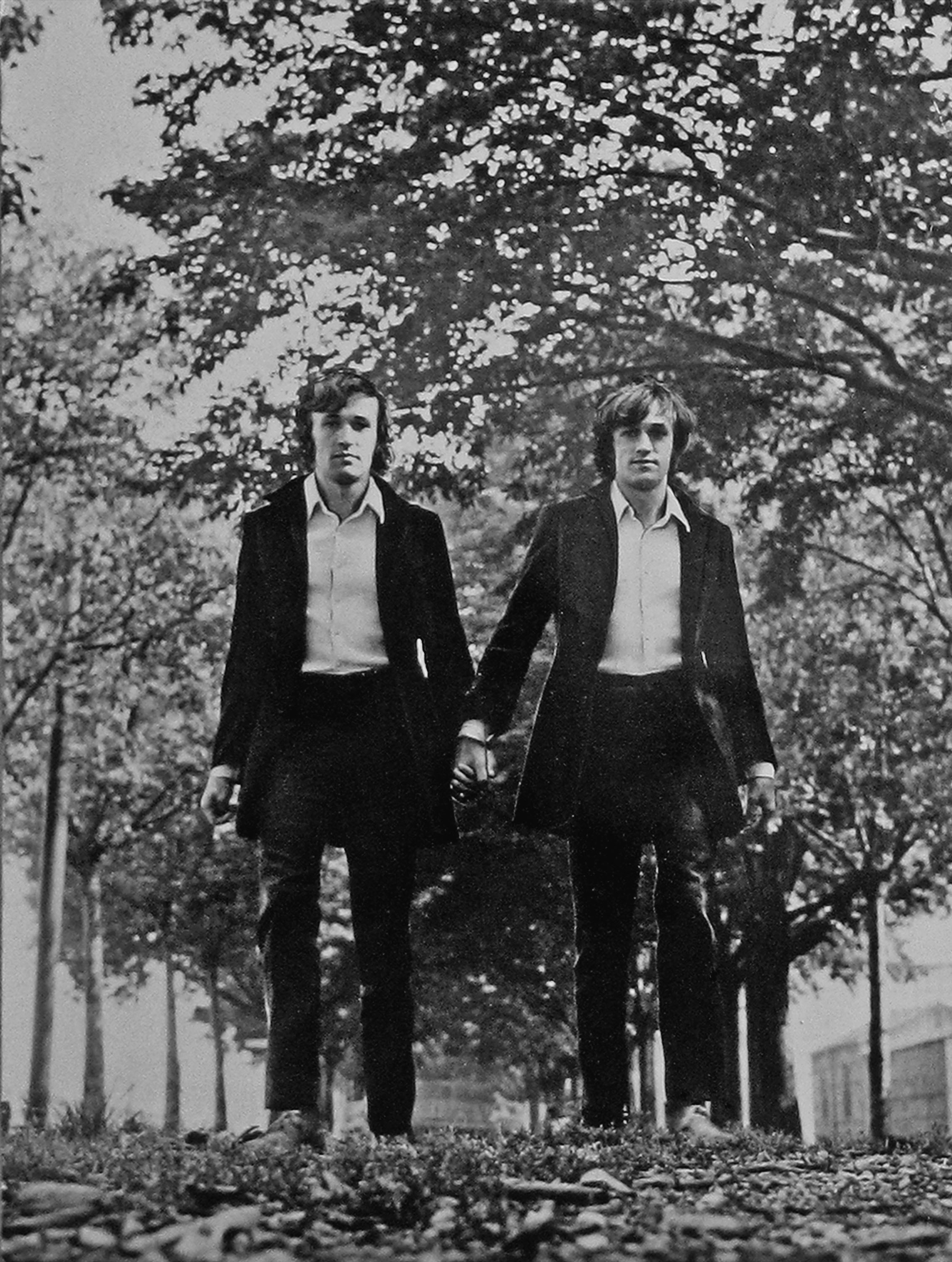

multiplying. In Shaman/Showman, 1968, he emphasizes the double role of the artist as spiritual creator and entertainer. In the postal work Gemelli (Twins), 1968, a card

shows Boetti walking hand in hand with an imaginary twin and from this day onwards he started to sign and to call himself

Alighiero E Boetti (Alighiero AND Boetti).

Alighiero Boetti, Twins, 1968. Private Collection. © Alighiero Boetti

Estate by DACS / SIAE, 2012

This interest in self-portraiture

remains constant. He challenged the tradition in works like Autoritratto (Self-Portrait), 1969, a series of 12 photocopies

of his face, until the final Autoritratto (Self-Portrait), 1993-1996, a cast bronze of himself in a suit, a hose spraying

water on his head, a heating device hidden under the scalp producing a cloud of steam. On the balcony at Tate this life-size statue awaits us when we leave the last

room, a suggestion of a brain working all the time on new ideas, projects, surprises for us.

Leaving Turin for Rome in the autumn of 1972 and separating from the Arte Povera movement, Boetti

starts a journey on his own, both a spiritual and a physical journey. His travels to and stays in Afghanistan mark his life and his work in an indelible way. From

1971 until the Soviet invasion in 1979 the artist travelled twice a year to Kabul where in 1972 he opened with Gholam Dastaghir

– an Afghan business partner – the One Hotel, a small hotel of 11 rooms: a work of art more than an economic

activity.

After the first two rooms of the exhibition, the viewer

is free to choose his own path, starting to play his own game.

Alighiero Boetti, Alternando

da uno a cento e viceversa, 1993. Embroidery. ©Boetti Estate by DACS / SIAE, 2012.

Game Game and artistic production

are always linked to logical paradoxes, mostly in their ability to create something utterly new. In a broad sense, artists, scientists and inventors are adults who can go on playing, for the final results of their

activities are socially acceptable. The essential character of the game is

the predominance of the rules. Boetti defies the essence of the game pushing the rules to the utmost limits. Dama (Checkerboard), 1967, one of a series of boards realized during that year in different

sizes and styles is a seminal work: a punched wooden block with symmetrical symbols where, in the order of this disposition,

the author deliberately put

an error. We are confronted by the same challenge in Ordine e disordine (Order and Disorder),

1973, a work of 100 small, embroidered panels woven in Afghanistan scattered on the wall. The pattern of

distribution of the letters is the same but for one panel where it is reversed, Disorder and Order: is up to the viewer to

play the game, discover the different panel and accept all the conceptual consequences.

Alighiero Boetti, Mappa,

1994. Embroidery. Private Collection ©Boetti Estate by DACS / SIAE, 2012.

Plan The Plan is the strategy,

the option that the player can choose. Boetti in the series of works like Mettere

al mondo il mondo (Putting the World into the World), 1973-75 and Mettere al mondo il mondo a Roma nella primavera

dell’anno mille novecentosettantotto pensando a tutto tondo (Putting the World into the World in Rome in the Spring

of the Year Nineteen Hundred and Seventy-eight Thinking in the Round), 1978, sets the action as it will happen in each

and every contingent state of the game. In this way, he defines a set of arbitrary rules: a definite and complete algorithm

valid both for the artist and the viewer. But this is also the only way for the

viewer to truly “enter” the work. These, known as the “Biro

works,” are panels completely and painstakingly covered in colour, created by small segments of ballpoint pen ink, one

next to the other to saturate the entire surface. This technique requests an

enormous expenditure of time and to accomplish this task Boetti employed collaborators, mainly art students, increasing in

this way the uniqueness of the work. On each panel, despite the anonymity

of the maker, we feel and recognize the sensibilities and the personalities of the various individuals. An alphabet of white letters appears on a border and white commas, scattered on the coloured surface, combine to

form the phrase that gives title to the work.

Boetti used the same technique of the ballpoint pen to produce the series Aerei (Aeroplanes), after the first

work Aerei (Aeroplanes), 1977, realized in pencil and watercolour in collaboration with the designer Guido Fuga. On

a coloured sky, many different kinds of aeroplanes, both military and passenger, follow their own route, giving us a sense

of playful, joyful lightness.

Research

started in 1970 and realized with his wife Anne-Marie Sauzeau, produced a book, Classifying: The Thousand Longest Rivers

in the World,1977, and two monumental embroideries, I mille fiumi piu’ lunghi del mondo (TheThousand Longest

Rivers in the World), 1976-1978, a green embroidery (in the collection of MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main)

and the other one, 1976-1982, a grey embroidery (in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York). The rivers are listed starting from the Nile-Kagera, following a classification set by Sauzeau

and Boetti.

Alighiero Boetti, Aerei,

1989. Courtesy of Carmignac Gestion Foundation. © Aligherio Boetti, DACS 2011.

Game Plan In the Postal Works Boetti plays against Time. Time is his opponent; Boetti is both the sender and

the recipient. The work is trapped in a loop, for the journey ends where it started. The artist used different strategies: permutations, false addresses in order

to have the mail returned to the sender, stamps organized by colour, size and position on the envelope. For these works, the main contributors where the postal

services of different countries and the unintentional action of the single postman who put different words on different spots

of different envelopes.

End of the Sixties, a period marked by strong political involvement and attention

to what was happening in the entire world. In this environment Boetti created Dodici forme al 10 giugno 1967 (12 Forms from June 10, 1967), 1971, copper

panels each engraved with the map of a war zone. One of these, The Palestine, became the first map of the Territori

occupati (Occupied Territories), 1969, a monochrome embroidered by his wife Anne-Marie Sauzeau Boetti.

Alighiero Boetti, Installation

View, Sprüth Magers London, 2012.

The Maps, probably his iconic body of works, show the world in images with a single rule:

the flag, symbol of a country, substitutes the geographical representation of the borders. The first intuition of this project is in Planisfero Politico ( Political Planisphere), 1969-70, a printed

black/white planisphere where the colours of the flags reflect the political divisions. In 1971 the artist commissioned the Royal School of Needlework in Kabul to make the realization of what was to become

Mappa (Map), 1971-72. On the borders of this Map appear words in Italian

and Farsi. After this series, helped by his business partner Dastaghir, Boetti decided to entrust Afghan women with the weaving

of Maps and after the invasion of 1979 the production migrated with the refugees to the border city of Peshawar, Pakistan.

A room with only Maps. On the threshold

of this room large and full of colours embroidered maps make Boetti’s Game Plan fulfill its purpose: surprise and emotion.

The viewer is compelled to recognize something he thought he knew well or search for something new. On the walls of this room we can read the changes and the evolution from a Eurocentric map: on one hand the maps

have been rebalanced and reshaped following new scientific measurements and possible new parameters; on the other hand the

geopolitical changes, the birth of new countries, the disintegration of others as a result of political/ideological revolutions

bring variations to the borders of the single state/flag. Male intermediaries

were the only channel of communication between the artist and the women weavers. This situation, together with the availability

of colour thread, brought unexpected results like a pink Ocean in Mappa (Map), 1979. From this moment onwards, Boetti let the women free to choose the colour of the Oceans. On the borders of these maps appear Farsi patriotic sentences, messages of hope, Persian poetry.

Alighiero Boetti died in Rome in 1994. This exhibition highlights the role of this artist

as forerunner of ideas, behaviors, aspects we see now in the artistic production of today. The use of new media, techniques

and the discovery of inspiration in different cultures are central and in a certain way are the essence of Boetti’s

oeuvre. His engagement with other cultures and artistic traditions is on a level of empathy and open interest. The constant discussion on authorship, so relevant these days, is shifted to a different level

by the involvement, the intertwined, complex relationship between Boetti and his collaborators. Whether they were art students or Afghan weavers, cartographers or designers, they were all, in Boetti’s mind,

no mere makers but participants and contributors to a cultural and artistic adventure.

Amongst the works shown in the exhibition at the Sprueth

Magers Gallery to coincide with the retrospective at Tate, Il Muro (The Wall) is a reconstructed wall as

it was in Boetti’s studio in Todi, Umbria. It’s a floor to ceiling hanging of small works, cards, photographs,

drawings, memories, an intimate insight into the artist’s thoughts.

Floriana Piqué is an art critic and independent curator. She

lives and works in London.

Alighiero

Boetti: Game Plan, Tate Modern, London, February 28 to May 27, 2012.The exhibition was shown at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid, October 5, 2011-February 5, 2012, and will travel to the Museum of Modern Art, New York, July 1-October1, 2012. Alighiero

Boetti, Sprüth Magers London, in collaboration with Le Case d’Arte, February 28-March 31, 2012.

|