|

This past autumn I visited the New York home and studio of

Elaine Reichek as my most recent studio visit with women artists whose work I

have followed for 25 years or more and have been writing about for this series.

I took the bus uptown on a bright Sunday morning to meet her for the first time

after spending so much time with her work. As I entered her light-filled home,

I was immediately taken with her work displayed on walls and tables. She

brought me iced coffee, chocolate pizelle cookies, and large, delicious

crackers I had not had before as we chatted about her life while sitting on her

deck in the sunshine. The beauty of her home and work matches this artist’s

elegance and hospitality.

We discovered

that we went to the same high school in

Brooklyn, although not at the same time. I laughed later, when I thought of the

other great women who graduated from there, including Ruth Bader Ginsberg and

Carole King who sang her Tapestry. I

like to think there is something in the water there that made us, like places

where you can only get good bread (it is always said to be the water that makes

the difference). Anyway, unbeknownst to us, we shared the same streets and

hallways and stops on the D train. For me, there is some sort of strange

comfort in knowing we had occupied the same longitude and latitude, but that is

another story.

Elaine Reichek, Swatches, Albers 1–3, 2007. Digital embroidery on linen. Each unit 12 x

10", overall 12 x 35". Photo: Paul

Kennedy.

Scanning

through the many things to look at in her home, my eyes were drawn to a small grid of embroidered squares made in reference

to Joseph Albers’s Homage to the Square, part of Elaine’s “Pattern Recognition” series of 2006 - 7.

Albers, a German-American artist who had been part of the Bauhaus before immigrating to the United States, had served as head

of the art department at Yale where Elaine studied, albeit after Albers’ retirement. Albers made a series of works with

multiple squares nested inside one another based on his theory of color relationships. Elaine’s versions are like small,

jewel-like stamps that replicate Albers’s famous nesting squares of color, only instead of being painted they were made

on a digital embroidery machine. They have zigzag edges that look as though they were cut with pinking shears to emulate the

look of swatches used for selecting fabrics and matching colors. The pinking shears’ zigzag is especially amusing as

these sewing scissors were created to stop woven fabric from unraveling, something neither painting nor digital embroidery

does. I can read Elaine’s appropriation of Albers as a feminist gesture,

particularly as she renders his painted images in the traditionally feminine form of embroidery, but the fact that she used

a digitally-driven production method instead of stitching them by hand, as she had done in earlier work, telescopes a history

of image-making technologies that encompasses the paint brush, the embroidery hoop, the mechanical embroidery machine, and

the computer. There is also play in these works between the ideas of art and craft (the replication of Albers’s art

in a medium usually thought of as craft) that is singularly appropriate in light of her work’s implied connections with

the Bauhaus, whose philosophy included uniting fine art and craft, and the work of Albers’s wife, Anni, an artist who

designed fabrics and made pictorial weavings and collages.

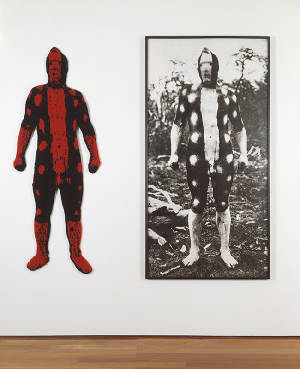

Elaine Reichek, Visitations, 1989. Installation view, Carlo Lamagna Gallery, New York.

Elaine’s work has

been informed by her interest in pattern and design since the early 1970s when she first started sewing her art. She felt

she needed a different playing ground from her male artist colleagues at Yale, who I can imagine took up all the space in

the discourse around painting. A bit later, she also made a series of knitted works; she started using embroidery in the early

1990s. There is a strong conceptual element to her work, which is frequently based on appropriated imagery Elaine researches

extensively, and often centers on contrasts between different modes and means of representation. She works in series, pursuing

the possibilities inherent in a particular set of images and ideas sometimes for several years. For over a decade from the

early 1980s through the early 1990s, she used ethnographic photographs of “native” dwellings, Fuegians, and Native

Americans as starting points. In these and other works, she reproduces the original photographs but alters them by hand-painting

over the painted body or over certain elements or inverting the image, partly to bring out the images’ inherent abstract

qualities, but also to demonstrate the extent to which the images are constructed and iconic, rather than objective records

of reality. She accompanied the photographs with hand-knitted replicas of their central features.

Elaine Reichek, Red Man, 1988. Knitted wool yarn and gelatin silver print. Overall

65 x 70 inches.

For the series “Tierra

del Fuegians” (1986 – 7) derived from early twentieth-century ethnographic photographs of an indigenous people

of South America, Elaine juxtaposed the photographs with knitted reproductions of Fuegian body paint that she also had repainted

in the photographs. These were the first of her works I saw, and they are an astounding group of images that have stayed in

my mind ever since. The conversation between the knitted body and the altered photo body is clear, yet thick with nuance and

mystery. They evoke the conventions of anthropological displays in natural history museums, while also functioning as abstract

art. By repainting the body paint on the photograph, Elaine allows the viewer to really see and appreciate the pattern that

was originally painted on another human being’s skin. Elaine describes her strategy in these works as “purposefully

misreading the patterns as abstraction, which is a Western idea, in order to address the way that seeing is culturally influenced.”

The knitted Fuegian body that hangs next to the photograph is an eerie double, recognizably human in form yet palpably different. On the

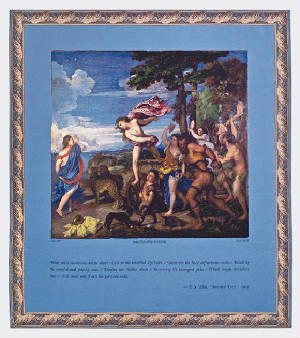

wall of Elaine’s bedroom is a full-scale mockup inkjet print of a magnificent tapestry appropriated from Titian’s

“Bacchus and Adriane” that has a woven blue border and a woven frame. The work also includes a fragment from T.

S. Eliot’s poem Sweeney Erect. Elaine’s name appears on the work alongside those of Titian and Eliot; she describes

these names as “the equivalent of a monogram, a convention from embroidery samplers.” The Titian depicts an important

moment in the story of Adriane when Bacchus and she perceive each other for first time and their eyes lock. Between the figures

is a large space of blue sky, so beautiful in both the original painting and the print mockup that my eyes lock onto it as

well.

Elaine

Reichek, Paint Me a Cavernous Waste

Shore, 2009-10. Tapestry. 118 x 107 inches.

Elaine’s series

“Ariadne’s Thread” (2008 -2012) addresses

the mythological tale of Ariadne, who helped King Theseus defeat the Minotaur

by giving him a thread to use to find his way into and back out of the

Minotaur’s labyrinth, only to be abandoned by Theseus afterward. Ariadne is vindicated, however,

as she marries the god Bacchus and thus becomes immortal. Elaine has retold the

story in a series of seventeen works: sixteen hand-sewn or digitally produced

embroideries and the newest, the tapestry made to her specifications in Belgium. Each work

appropriates representations of

important moments in Ariadne’s story as rendered by art historical figures

ranging from George Frederic Watts to Matisse to John Currin. The tapestry, Paint Me a Cavernous Waste Shore (2009

–

10) based on Titian’s Bacchus and Ariadne

(1520 – 23), is the capstone of the series and it was included in the

current Whitney Biennial. Each embroidery includes a literary quotation from

one of the versions of the story or from a poet or writer who refers to Ariadne

in another context, such as the quotation from T. S. Eliot that serves as the tapestry’s

title.

|

| Elaine Reichek, Embroidery in process. Photo: Deanna Sirlin. |

Elaine describes this series as a “minicompendium

of the possibilities of thread,” and this is true in both its literal and figurative senses. In addition to juxtaposing

her uses of thread with painting, drawing, and writing, Elaine also juxtaposes mechanical means of production and reproduction

with handicraft and digital technology. In addition, the series is an extended meditation on how Ariadne has been depicted

in the histories of art, literature, and even music (since she includes Aridadne auf Naxos, the 1912 opera by Strauss and

von Hofmannstahl) and the symbolic valences of the thread and the labyrinth. The work is thus an art historical minicompendium

as well that contrasts the linear with the painterly (both translated into embroidery, of course), the carefully composed

with the spontaneous. Through the images and quotations Elaine presents, thread becomes the thread of a narrative or an artist’s

line or a line of handwriting. The labyrinth can be a puzzle the world presents us to solve, or it can be the labyrinth of

the inner world we each create of ourselves, as André Gide suggests in one of the quotations Elaine cites. At the level of

narrative, we may identify with the Minotaur, as did Picasso, or with Ariadne, as does Elaine. The series shows how the mythological

tale has become a matrix for centuries of accreted imagery and ideas. Ariadne-like, Elaine has always offered us threads with

which we can navigate the labyrinths of reproduction, representation, and reworking that constitute our history and culture. For

me, an artist who embroiders, [the myth of Ariadne] is powerful and symbolic as the story of a thread—for the key, the

lifeline, that Ariadne gives Theseus is in fact a thread, which he lays down to guide himself through the labyrinth. The

labyrinth itself, of course, is an enduring symbol, around the world and across the millennia—one of those images that

are invested with significance in the unconscious. The Minotaur, as a fusion of animal and man, has been seen as a sign for

the struggle to understand what it is to be human. And the story is one of emotional risk, in which both the punishments and

the prizes that risk entails are fully realized. In loving Theseus, and helping him and running away with him, Ariadne cuts

herself off from her previous life. She gives up everything, and loses—but then she triumphs, trading in a king for

a god, the Apollonian for the Dionysian. And the life of the artist is that of risk. If the tool to

finding our way is the thread, then Elaine has never floundered or lost her way.

Elaine

Reichek had a solo exhibition at Nicole Klagsburn in NYC, which closed on March

24, 2012, and is in the Whitney Museum’s 2012 Biennial (March 1 to May 27,

2012). Her work will also be exhibited at the São Paolo Biennale, The Imminence of Poetics (September 8 – December 9, 2012). She is

also

currently in Points of View: Twenty Years of

Artists-in-Residence at the Isabella

Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston, MA (January 19 – August 13, 2012),

and is the recipient of a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship at the Hirshhorn Museum

and Sculpture Garden, Washington,

D.C. and Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, New York. Her series

Ariadne’s Thread was the subject of a

solo exhibition at Shoshana Wayne Gallery in Santa Monica, April 2 – May 21,

2011.

Deanna Sirlin is an artist based in Atlanta.

She is writing

a series of profiles for TAS of living American woman artists whose work she has been following.

|