|

Alberto Burri: Form and Matter at the Estorick Collection

by Anna Leung

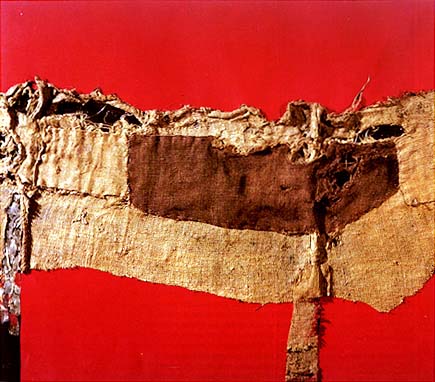

Alberto Burri, Sacking

and Red, 1954. Tate Collection.

Alberto

Burri is not well known in Britain and this exhibition at the Estorick Collection is his only retrospective in the past forty

years. Represented by one solitary painting, Sacking and Red, 1954, in Tate Modern, his contribution has tended

to be overshadowed by the dominance of Abstract Expressionism and eclipsed by his compatriot Lucio Fontana’s intense

dramas of punctured and slashed canvases; slashing was a way of heightening interaction with the physicality of the canvas,

a procedure that Burri did not need to adopt in order to achieve a similar goal. Nevertheless, these two artists have much

in common; both moved the concept of painting out of the domain of representation, whether figurative or abstract, into that

of object, a surface and site of operational processes, but it could be argued that Burri’s influence on many of the

young artists who were to make up Arte Povera makes him the greater of the two. . Alberto Burri was born in Citta di Castello in land locked Umbria

on March 12 1915 and graduated in medicine from the University of Perugia. Till 1943, when he was captured by the British

in Tunisia, he practiced as a doctor in the Italian army. Encouraged by another inmate of the camp who had been a Futurist

he began to paint when a prisoner of war in Hereford, Texas and on his return to Italy decided to take up painting professionally.

As can be seen from the first room, he started out as a figurative expressionist whose images have a melancholic appeal and

gradually veered towards a delicate form of abstraction inspired mostly by Klee and Schwitters. By the end of the forties

and into the fifties he began to experiment with the physical properties of his materials, using both conventional oil and

industrial paints. Taking up from the Futurists, especially from Boccioni who, in his Technical Manifesto of Futurist Sculpture,

had exhorted sculptors to experiment with a far wider range of materials than conventional ‘noble’ materials such

as bronze or marble, he began to explore the various textures of paint and to integrate them with a wide range of materials

such as tar, rubber, pumice stone and burlap sacking, his signature material, to create what were in effect large scale collages.

White Cretto, 1975, Private Collection

This fixation and fascination with the physicality

of materials was very much part of new developments among European artists. By the mid-fifties European abstraction had ceased

to be post-cubist. Indeed what we see happening in the period after World War II is a far greater acceptance of plurality

and diverse forms of expression. No one style dominated. No one style dominated. The ideological credibility of art as a utopian

blue-print exemplified in the geometric canvases of Mondrian or Ben Nicholson was no longer convincing and was even viewed

with a certain distrust because the impulse behind it was motivated by a rationality and logic that seemed uncomfortably close

to totalitarian thinking. Rejecting this sort of doctrinaire thinking European artists recognised that nature speaks to us

through our bodies, through pain and pleasure, and the canvas increasingly became the site of an existential encounter with

reality. Art Informel, which originated with the French critic Michel Tapie whose book entitled ‘Un Art Autre’

(A Different Art) represented a total break with modernism, directed the artists’ attention to immediate experience

as the source of any knowable truth through an emphasis on the tangible.

Rejecting

modernism’s rationality and its belief in an aesthetic or transcendent ideal, the artists brought together under this

umbrella group of Art Informel developed a concept of painting that prioritised the expressive gesture of the artist while

experiencing the canvas as a total encounter with reality, materiality revealing the basic ground of reality. The canvas was

no longer seen as a transparent screen but as an opaque field of action, an arena in which the gesture of the artist remains

a sign or gesture rather than being transformed into a particular image or form. What Art Informel denied was not form per

se but the idea of form originating out of some preconceived plan or intellectual theory. It therefore emphasized spontaneity

and the role of chance, but equally crucial, and of signal importance to Burri, is the notion of immersion in the materiality

of the medium. However, it is important to note that this form of gesture was neither related to the psychology of the individual

artist, as it had been in Abstract Expressionism, nor reaching towards something transcendent. On the contrary--Art Informel

centres on the physical reality of the painting as a literal rather than illusionistic object and as a celebration of materials

and their properties. It is this aspect of Art Informel that links it back to its Italian Futurist roots and forwards to Arte

Povera and their use of humble materials.

Iron, 1960, Calvesi Collection

As part of the Art Informel circle of international

artists that included Dubuffet, Tapies Fontana, Wols and Fautrier, Burri stressed the material reality of the canvas in such

a way that though the material he uses is instantly recognisable for what it is – there is no pretence and he leaves

tell-tale signs such as lettering on his sacking -- he imbues it with a certain individual aesthetic sensibility. Playing

off variations in weave and textures against one another, the natural colour of the burlap sacking is juxtaposed against fiery

reds and stark tarry blacks, and charred paper is transformed into a filigree of silver and black. It’s all too easy

to liken his earlier canvases to scars, lacerations and wounds – an obvious parallel given Burri’s medical background

-- and to see his later work as metaphors of decay and an indictment of industrial waste. But Burri’s canvases represent

a tenuous balance between abstraction and evocation, and between form and matter, and demonstrate, possibly despite himself,

the mystery of an alchemy of form summoned up by the artist from the crucible of matter. What I think is extraordinary is

that as we move from one room to another we can appreciate how, despite the latitude given to spontaneity and randomness,

Burri ’s compositions reveal an innate, even a classic sense of balance, proportion and harmony which towards the end

of his career increasingly comes to the fore. Indeed, as time distances us from these canvases, which at first sight must

have been experienced as radically ugly in their rejection of conventional fine art materials, they seem to gain in a certain

mysterious depth of beauty which was after all what Burri was searching for. ‘I see beauty that is all’ he said

in reply to critics trying to elicit an interpretation or explanation from him.

Sack, 1954, Fondazione Magnani Rocca

Burri continued to work with unconventional materials,

mixing tar and rubber plus other industrial materials such as cellotex, an industrial insulation material, and scrap metal.

From the mid fifties he began to experiment by charring, scorching and melting his materials with a blowtorch creating what

he called his Combustiones and anticipating Yves Klein, Miro and Gustave Metzger. In 1951 Burri founded the Gruppo

Origine, which rejected naturalism and spatial illusion and highlighted the literal properties of the canvas. It is from

this time that he began to work in metals, possibly inspired by one of his co-founders Ettore Colla who created delicate sculptures

from scrap metal. In the sixties he produced a series of wall hangings made by welding together sheets of metal that had been

exposed to various procedures; and he titled these Ferri. They were followed in the seventies by another series made

by melting cellotex, which resulted in delicately cracked monochrome paintings such as his white and black Cretto,

on display in room 2. All these series continued to introduce a greater element of chance into his work and emphasised process

over the finished product. However, a change is noticeable in his later work. Although this work is still based on industrial

materials there is a marked shift to a greater emphasis on a harmoniously balanced composition that up till this point had

only been latent in his paintings and etchings.

Possibly because his work’s proximity

to Action Painting, Burri was first recognised not in his native Italy but in America. Dealers in New York and Chicago were

the first to acquire his paintings, and by the mid-fifties he was included in a group show in New York at the Guggenheim,

and in 1963 the Museum of Modern Art Houston put on a midcareer retrospective. He was probably the best-known Italian artist

in the post-war period, and both Rauschenberg and Cy Twombly admit to being influenced by him. This link with the United States

was made closer when in 1951 he married the American avant-garde dancer and choreographer Minsa Craig and thereafter began

to divide the year between Italy and California, spending the winters in Hollywood and the summers in Rome and his home town

Citta di Castello to whose Art Gallery he bequeathed the main bulk of his work. He died in Nice in 1995.

Though long overdue, this exhibition has given us the distance to appreciate the innate poetry that

lies in Burri’s exploration of mundane materials. Burri always insisted that meaning was contained within the compositions

themselves through the formal interplay of tensions and harmonies and the sense of balance that together embody a kind of

sensuous meaningfulness, and this is, I think, well borne out in this exhibition of his paintings and prints.

© Anna Leung

Anna Leung is a London-based artist and

educator now semi-retired from teaching at Birkbeck College but taking occasional informal groups to current art exhibitions. Alberto Burri: Form and Matter is at the

Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art in London from 13 January - 7 April 2012. All images by Alberto Burri © Fondazione Palazzo Albizzini, 'Collezione Burri', Cittą di Castello / DACS 2012

|