|

|

Paul Gauguin, Embellished Frame of Frame with Two Interlaced "G's", 1881-1883. Carved walnut containing photograph of the artist. Musée d'Orsay, Paris, Gift of

Mme Corinne Peterson in memory of Frederick Peterson and Lucy Peterson.

Gauguin: Maker of Myth

Tate Modern, London, 30 September, 2010 - 16 January, 2011

by Anna Leung

It is appropriate that an exhibition which has as its stated aim to

demythologise Gauguin and yet present him as a maker of myths should begin with

a series of self-portraits in which the artist assumes different personae.

Starting with the Sunday painter equipped with his mandatory bohemian fez it

ends with a disconcerting image of Gauguin, invalided and bespectacled, shortly

before his death in 1903 from syphilitic heart failure while in self-imposed

exile in the Marquesas Islands. He was, one is tempted to say, the

self-sacrificial victim of his own ambitions, for he could have chosen to

return to France for treatment and survive a few more years. It was a risky

wager and he won, for by 1906 he was being posthumously honoured with a major

exhibition at the Salon d’Automne. He knew that for the myth of the ground

breaking anarchic and visionary artist to become a reality he had to forfeit

the comfort of family, friends and, from a more opportunist point of view, Paris.

As Daniel de Montfreid, the friend, to whom was entrusted the business of

selling his canvases in Paris, reminded him, he was ‘that

extraordinary,

legendary artist who sends from the depths of Oceania his disconcerting,

inimitable works, the definitive works of a great man who has disappeared, as

it were, off the face of the earth.’

To retain this status Gauguin made his own

life an integral part of his narrative strategy and in so doing set a precedent

for many modern and postmodern artists whose lives as celebrities risk

cannibalising their lives as artists. Myth suggests something

inexplicable and impenetrable but contrary to these connotations there is much

cause and effect in Gauguin’s life. Gauguin was a late developer. From the age

of 17 he spent several years traversing the globe as a merchant seaman and then

improbably was transformed into a bourgeois gentleman and family man working at

the Bourse as a ‘coulissier’ (an accountant or bookkeeper rather than a stock

broker) where he was in a good position to speculate on stocks and commodities

and provide his Danish wife, Mette, with the luxuries she craved. It was during

this period that he became a Sunday painter and began to collect Impressionist

paintings including canvases by Cezanne - he came to own six - and Pissarro.

But in 1882 he lost his job due to an international financial crash, and it

must have seemed logical to him to abandon his financial career and attempt to

pursue an artistic one. He was already aware that the Impressionists had challenged

the dominance of the Salon, describing their independent exhibition as a ‘battle

against a fearsome power made up of Officialdom, the Press and Money.’ Gauguin was astute enough to

recognise in painting a commodity that could gain in value and to appreciate

the increasing importance of the critic’s role of validating innovation in a

market no longer automatically certified by the prestige of the Salon. Despite

his frequent diatribes against critics and literary men poking their noses into

the visual arts he fully realised the importance of marshalling fashionable

young critics such as Felix Feneon, Albert Aurier

who framed the first

definition of Symbolist art as the subjective expression of an idea in terms of

form, and Octave Mirabeau, who enlisted Mallarme's help when Gauguin was trying

to drum up the necessary funds to return to Tahiti. This resulted in a

Symbolist Banquet where Gauguin was acclaimed as the new leader of the

Symbolist school of painting, an accolade indeed for an ambitious young artist

who knew in more senses than one where he was going and the price he would have

to pay. These were career moves conducted in the

artificial light of publicity motivated by an acute awareness of the market

that was never far from Gauguin’s thoughts, even when in Tahiti’s earthly

paradise. Offstage, the figure holding together all these life-changing

events was

the Franco-Spanish businessman Gustave Arosa, who had become Gauguin’s guardian

when he befriended Gauguin’s mother, Aline, who had been forced by

circumstances to take up a trade as a seamstress. It was through Arosa that

Gauguin obtained his position at the Bourse, through him that he was introduced

to his future wife, Mette Gad, and through him that he met Camille Pissarro,

who tutored Gauguin and handed down his then advanced views on painting. Since

Gustave Arosa was a collector of advanced art, Gauguin would have been exposed from

his teens to avant-garde painting, initially the Barbizon School, but later

paintings by Pissarro and other independent minded artists. In this way his

eyes had already been tutored to Impressionism’s plein air vision with its

informal rendering of contemporary life and its transmission of the faster pace

of urban society through asymmetrical compositions, figures spied from awkward

angles, its vibrant colour field and its emphasis on the materiality of the

medium that revealed the process through which the painting had come into

being. He had no need to shake off the shackles of academic conventions, no

need to relearn a new pictorial syntax that jettisoned chiaroscuro and dramatic

gesture. To this extent he was not a late developer but already ahead of the

game.

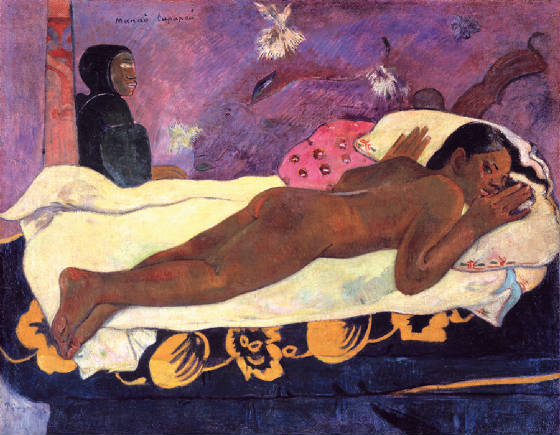

Paul Gauguin, Manao tupapau (L'Esprit vielle/The Spirit of the Dead Keeps Watch), 1892. Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, A. Conger Goodyear Collection, 1965.

Moving

away from Impressionism

By the beginning of the 1880’s Gauguin was beginning to be recognised as

part of ‘la nouvelle peinture’ as the Impressionists were first known. Though

still a Sunday painter working at the Bourse, from 1879 to 1886 he contributed

to the annual Impressionists’ Independent exhibitions, first with a sculpture

of his wife, Mette, but later, as he came under the tutelage of Pissarro, with

portraits, still-lifes, and landscapes featuring the loose brush work

characteristic of the Impressionist style. His eventual turning away from Impressionism’s emphasis on

optical realism and its insistence of the particularity of things (Zola’s

corner of nature) caused the breakup of his friendship with Pissarro, who never

quite forgave him for his defection from the humanistic and progressive values

of the Impressionists for what he deemed to be no more than decorative

primitivism. Gauguin came to regard Impressionism as an error that only he and

Cezanne stood out against. Neither was content to capture the mundane

contingencies of everyday life and both scorned a literary or literal account

of experience. But whereas Cezanne was intent on capturing the ever shifting

interstices that make up our perception of reality within a shimmering tapestry

of brush strokes and was essentially a classic painter, Gauguin cast a far

wider net and began to see himself as a ‘savage’ able to sense unseen primal

forces and to move beyond the limits of the real. This is what really

interested him, the liminality and interconnectedness of dream and reality, and

he accorded equal if not more importance to the realm of the imagination and to

the way it reconstructs what we construe as reality than to the actuality of

our daily lives. This is already

evident in the two portraits of his children, Aline in The Little One is

Dreaming (1881)]

and Clovis (Clovis Asleep, 1884) whose

schematic dream journeyings we seem to see projected against the walls of their

bedrooms. For Gauguin, art was not about what you can see with the external

eye; it was not about visual data, but was essentially cerebral, philosophical

and poetic.

This may all sound abstruse but Gauguin was well aware of the need for a

new pictorial language to clothe these ideas and his motifs were drawn from a

wide variety of sources, Japanese prints, childrens’ book illustrations,

especially by English illustrators, and the images d’Epinal, the peasant broad

sheets that had already inspired Courbet, all visual material denied access to

the realm of the Fine Arts. But it would be mistaken to think that Gauguin had

turned his back on Western art. It

was always with him, for wherever he went he carried a portable library of

photographs and drawings which he described in a letter to Redon as ‘a whole

little world of comrades that bring me pleasure.’ These includedm], among others, reproductions

of the Parthenon horsemen, Delacroix’s Women of Algiers, Manet’s

Olympia, Puvis de Chavannes’s L’Esperance as well as the Buddhist reliefs

from Borabadur in Java, a nude by Cranach and a series of pornographic photos

from Port Said. Photography gave him access to a world of images, which meant

he could immerse himself in the confluence of art’s histories. Originality may

have been the leitmotif of the avant-garde artist, but many borrowed, some

would say plundered, from past masters. Though down the ages artists have

succumbed to various influences, photography ushered in a new phenomenon, which

we tend mistakenly to associate with postmodernism, by which the study of nature becomes subordinate to that of

culture in terms of pictorial material previously not readily available to past

artists This reusing of already

existing figures, gestures and poses constitutes part and parcel of Gauguin’s

primitivism; his fusing of elements coming from different pictorial sources

which then take on an independent emotional and sensual register can be

paralleled with his fusing of syncretic elements from different belief systems

and religions to recreate what was lost of an indigenous Tahitian culture. This

vision spoke of a renewal, outside of old Europe, that was internationalist and

globalist in tone and which marks him as unusual in his empathetic attitude to

non-western culture but which also provided him the maverick status he sought

as an avant-garde artist.

It is therefore not Gauguin’s subject matter that placed him apart from

the Impressionists but a synthesist interplay between image and idea, or vision

and visionary, that allied him to the Symbolists. Symbolism depends on the

creation of a sense of mystery, and works through suggestion rather than

through literal or direct representation. It permits the artist to journey

inwards into a dream world but in Gauguin’s case and that of many other

artists, such as Ensor and Munch, they did so to highlight the pain and

alienation felt by the artist excluded by society. This feeling of ostracism is

conveyed in his picture Bonjour M. Gauguin (1889), inspired by Courbet,

in which the

solitary artist is seen as a kind of refugee forever fated to eke out an

existence on the margins of society. When faced with his outsider status

Gauguin may have brought to mind Gustave Arosa’s collection of Peruvian

pottery, reawakening memories of his own childhood spent in Lima whose culture

was therefore a part of his own, and perhaps Gustave’s brother Achilles Antoine

Arosa’s mementoes, water colours and sketches, of a voyage taken to Tahiti and

the Marquesas Islands in 1844. The lure of the tropics would have been more

than compelling

Paul Gauguin, Tahitian Faces, c. 1899. Charcoal on paper. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Purchase, The Annenberg Foundation Gift, 1996.

Fuire

La Bas

The

cultivation of the exotic and of the occult was not new in French

artistic and philosophical circles. It was an important vein of French

nineteenth century Romantic literature that figures in the poetry of Gerard de

Nerval and Baudelaire. Both were seekers of solace in some oriental idyll which

took them to a frontier between reality and dream, their poetry opening doors

to invisible worlds. Nerval actually travelled to the Levant, Baudelaire only

as far as the horizons of his own imaginings. Like Gauguin, who followed in

their footsteps, they were fascinated by the religious concepts of non-western

peoples as a spiritual treasure that had been lost. Implicit too in their

writings was the idea of the accursed poet, ‘le poete maudit’, a

forerunner of Gauguin’s

pro-active ‘savage’ at odds with contemporary urban society with its

instrumental values and its positivistic faith in technological progress. Modern philosophical ideas about

primitivism go back even further to Rousseau and Diderot who contrasted the

freedom of savage men living in harmony within a state of nature with the

concupiscence and depravity of the sophisticated European. Diderot was the

first to fasten on to the sexual freedom of the Tahitians, contrasting it with

the prurience and depravity of their European counterparts whose sexual mores

were based on double standards. Such insights were proffered as a means of

creating a better society based on primitive virtues, but did not advocate a

literal return to a state of nature.

Equally important

artistically, especially in view of Gauguin’s subsequent experiments in

ceramics and wood carving, were his visits to two ethnographical museums in

Paris that specialised in non-Western artefacts, masks and figures as well as

highly decorated everyday objects. Then in 1889 there was the vast

International Fair where Gauguin was entranced by the Javanese village and

began to toy with the idea of emigrating to Vietnam, Cambodia or the recently

annexed Tahiti. But the most accessible source for Gauguin’s exotic imaginings

was a popular novel, The Marriage of Loti by Julien Viaud, the pseudonym

of an ex-

merchant seaman, Pierre Loti, which had been recommended by an enthusiastic van

Gogh. It’s from this time that escape from Europe became an idée fixe in

Gauguin’s mind, though the actual shift from a practice based in Paris to one

premised on some exotic otherness probably predated this and originally took

effect during his stay in Martinique in 1887. The novel described in diary form

the romance between a fourteen year-old Tahitian girl and Loti, a British

midshipman, which was doomed to failure because of insurmountable racial

differences, the dangers of miscegenation to children being especially high on

the list. Gauguin may have started

out with racist opinions close to those of Loti but his ten year stay in Tahiti

changed them and in the end he came to believe in communality and cultural

kinship conjoining all races. Consequently, though it was not till his exile to

the Marquesas Islands that he made friends with his native neighbours, he stood

his ground against a tide of openly racist publications that had as their

objective to provide an ideological support for imperialism and

colonialization. Bringing French civilisation to the colonies was not Gauguin’s

aim. On the contrary he described his own geographical displacement as a

desperate flight from civilisation in order to ‘cultivate’ his own ‘primitiveness

and savagery.’

Placing himself under the aegis of Rousseau, Gauguin undertook a quest that was

both a search for origins and an inner journey where reality and dream became

fused. But in actual fact Gauguin’s residence in the tropics was dependent on

the good offices of the French bureaucracy and its monthly postal service.

Not that he was alone in this search. By the end of the nineteenth

century the cult of going away was fairly widespread. It was certainly not

restricted to France. All over Europe artistic communities or colonies were

springing up, made possible by the opening out of the railways and motivated to

a large part by the need for an economically feasible way of life. Equally

important was the idealised image of the rustic peasant as yet uncorrupted by

the sophistication and gross materialism of urban society. Long before Gauguin

discovered Brittany as an area that had escaped the modifications of modernity

and therefore retained a hold on its age old archaic beliefs it was already a

popular centre for artists and tourists alike. But Gauguin was no topographical

artist and what he was attempting to depict was an inner vision that revealed

the determining role of the imagination in perception. In a letter to van Gogh

he described his ground breaking painting The Vision after the Sermon (1888)

as ‘a struggle (that) only exists in the

imagination of the people praying.’ Animals, too, often stood for external signifiers

of inner mental

states the most noticeable being the fox, possibly an alter ego, in The Loss

of Virginity 1890-91

and again in his 1889 self mocking wood relief Soyez amoureuses, vous serez

heureuses (Be in love and you shall be happy). This carving completely breaks

with the conventional unities of renaissance perspective and represents such a

complete breach with conventional assumptions based on good taste that it seems

to have as its expressive goal the creation of something ugly and in this way

to insist on the artist’s own barbarity, a move which was to become a typical

avant-gardist stratagem.

Twice Gauguin attempted to create an artists’ commune, once in Brittany

and then with van Gogh in Arles; neither met with success. He told a journalist

that his Christ in the Garden of Olives (1889) refers to this ‘crushing

of an ideal

and a pain that is both divine and human.’ His extraordinary Self

Portrait, Vase in

the Form of a Severed Head which may allude to van Gogh’s severing of his

own ear lobe, made in

the same year, carries a similar message. It functions as a self-portrait as

victim and saviour. It is this ambiguity, this plurality of experience that

mingled myth with reality that would in future provide Gauguin with his subject

matter whether in Brittany or in Tahiti, and for which primitivism would

provide an artistic template.

Primitivism

Gauguin’s primitivism was forged in Brittany not in Tahiti. His retreat

to Brittany was forced upon him partly by his failure to fend for his family.

After a number of years constantly beset with worries about money and

unsuccessful attempts to provide for Mette and the five children (who had

returned to Copenhagen in 1884) by taking jobs as unlikely as a tarpaulin

representative and a billposter, in 1886 Gauguin travelled to Pont Avon. This was

a picturesque village already frequented by artists and tourists. Moreover

several academic artists had made their names in the Salon by depicting the

Breton peasantry as representative of an archaic past steeped in an esoteric

religiosity so what Gauguin and his acolytes chose to highlight was not new.

What was new was the pictorial language they made use of, its absence of

perspective and of tonal modelling, i.e. its musical, decorative and

anti-naturalistic aspects that looked back to earlier so called ‘primitive’ art

forms: to Cimabue, for instance, as against the illusionistic accuracy of the

High Renaissance masters.

It was here, working alongside such younger artists such as Emile

Bernard, who later disputed Gauguin’s right to spearhead the new Synthesist

movement, that he began to distance himself from the Impressionists by

insisting on the artist’s right to simplify and distort reality in order to

create an expressive image, colour especially functioning as an imaginative

equivalent of nature rather than a literal likeness. What Gauguin represented

inhabits an ambiguous space that belongs neither to the historical nor the contemporary,

but to an in-between reality situated beyond objective or empirical knowledge.

However, though remote from political issues and seemingly at variance with a

secular and materialist society, his Synthesist vision was acknowledged by the

critic Albert Aurier as betokening a new social order and, therefore, avant-garde

by definition. Gauguin’s paintings were interpreted by contemporary critics as

politically progressive and, therefore, cutting edge despite his

neo-traditional treatment of colour and form and the regressive and escapist

tendencies that led him to resurrect a nostalgic dream of a fast-disappearing

society. This was an analysis that mirrored the ambiguities of Gauguin’s own

character, which leaned towards the aristocrat as well as towards the savage.

Paul Gauguin, Soyez amoureuses vous serez heureuses (Be in Love and You will be Happy),1889. Carved and painted linden wood. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Arthur

Tracy Cabot Fund.

|

|

|