Susan Sontag was ultimately proved correct. ‘Silence’

she writes ‘remains inescapably a form of speech

….and an element of dialogue.’ The concluding sentence to one section of her essay ‘The Aesthetics of Silence’,

it was written in 1967, a year before Duchamp’s death when it was still thought that he had completely renounced Art

in favour of chess. His silence therefore denoted an extreme position within an anti-art aesthetic that effectively liberated

him from the art world and its machinations. It was then not known that for twenty years he had been beavering away in secret

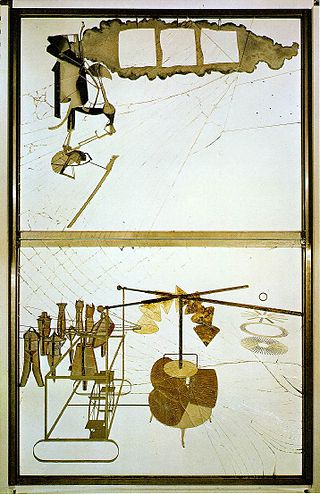

on an installation that was to contradict this iconoclastic stance. Yet another coup de theatre, Étant donnés was only

unveiled in 1969, joining his other major work The Large Glass (1915-23), which it complements, in the Philadelphia

Museum of Art. Not only did Étant donnés upturn everything that he had seemed to stand for with its return to

academic figuration, manual skills and narrative but it cleverly substantiated Duchamp’s claim that the creative act

does not solely belong to the artist but equally to the viewer whose interpretation ideally completes the work. The scene

in this case can only be viewed through two small holes placed at eye level turning the spectator into a willing or unwilling

voyeur. But equally important Étant donnés proved that though Duchamp had gone underground he had continued to pursue

various lines of artistic research, assembling the stage and all the props for Étant donnés in a second studio to which

no one had access save himself, one assistant, and his wife. His silence turned out to be a mute dialogue and his apparent

detachment was part of a role he was playing.

With

this act of self-containment and self-contradiction Duchamp upped the stakes in his own status as an artist whose influence

was to take him safely into the twenty-first century. His fabled indifference worked in his favour and ensured him a splendid

afterlife as the eminence grise behind conceptualism. But it is not in this capacity that he is celebrated in this extraordinary

exhibition but rather as a father figure to a loose group of four American artists during the 1950’s and 60’s,

two visual artists, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns, the composer John Cage and the choreographer Merce Cunningham who

all collaborated with one another at various stages of their careers and who, in different ways and through different thought

processes, were all inspired and influenced by Duchamp to take their respective art practices in a totally new direction.

It is noteworthy that in

was in the United States that Duchamp was most revered and his influence most marked. Duchamp and America had developed a

special relationship of mutual support. The Armory Show in New York had provided his controversial painting Nude Descending

a Staircase with its first exhibition venue when in 1912 it was rejected, supposedly for its title, by the Puteaux Cubist

group to which his brothers belonged, and who dominated the Salon des Independents. And though his first readymades, Bicycle

Wheel and Bottle Dryer (both on display) were begun in Paris in 1913 their actual nomenclature was adopted in the

States where they were first exhibited in 1916. The relationship between Duchamp and America proved to be symbiotic. America

provided him with a home, and eventually citizenship, and gave him his first retrospective exhibitions in 1963. In return,

Duchamp took on the role of America’s own tutelary French artist incorporating his pose of cool, cryptic, cerebral,

iconoclastic dandy into the history of American modernism as well as taking on the ancillary role of chief advisor to many

art galleries, dealers and collectors.

|

| Marcel Duchamp The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors Even (The Large Glass), 1991-92 (replica of |

His example was to be of particular importance to the second

generation of Abstract Expressionist artists such as Rauschenberg and Johns who became disenchanted with Abstract Expressionism,

rejected Clement Greenberg’s all too narrow Modernist doctrine with its emphasis on optical purity, and found that Duchamp’s

detachment opened new doors. Duchamp, especially the Duchamp who transformed himself into the femme fatale Rrose Selavy (eros

c’est la vie), represented the antithesis to the macho rhetoric of Abstract Expressionism, which insisted on the authenticity

of the artist and his ability to reach or reveal a transcendent truth. Rauschenberg (1925-2008) and Johns (1930-) were sceptical

about the artist needing to express his innermost self in a gestural act of spontaneous creativity or were reluctant to do

so. Duchamp, with his elegant playfulness and aesthetic of minimum effort, challenged the existing Expressionist His Readymades

were just ‘thing[s] he called art’ which, as he explained, ‘I didn’t even make … myself’.

If there was no inner self then expressionism’s angst ridden form and its supposed existential force that was equated

with American maleness was voided of meaning. Meaning, according to Duchamp, was brought to an artwork through the viewer

rather than inhering totally in the body of the work and its maker. This as we shall see was a far safer place for creatively

talented individuals to be in troubled times.

The sanctification of silence and the cult of indifference made sense to a generation of artists

who were careful not to get maligned by a culture of conformism characteristic of post war America which, fearful of increasing

Communist domination world wide, was entering paranoid mode. The House Un-American Activities Committee, which became permanent

in 1945, focused its attention particularly on accusations of Communist sympathies, accusations Senator Joseph McCarthy employed

regularly against his perceived enemies throughout the early 1950s. Given this political backdrop it is not surprising that

artists took refuge in an aesthetic of indifference and a disavowal of meaning, though, as we shall see, indifference need

not necessarily be equated with a negative state of mind. Moreover, it is probably no coincidence that these four artists

were gay. Silence and indifference represented convenient and appropriate modes of survival during a time of rampant homophobia,

a front as well as a shield against their own inner anxieties.

|

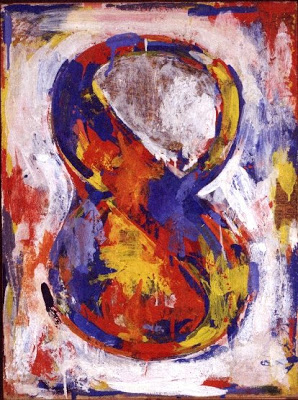

| Jasper Johns Figure 8 , 1959 The Sonnabend Collection, New York © Jasper Johns / VAGA, New York / |

Art historically, Rauschenberg and Johns,

along with Happenings, Fluxus, and French New Realism were categorised as Neo-Dada.This, too, indicates the link with Duchamp

and his deep affiliation with Dada. Belonging to a generation sickened and scandalised by the senseless carnage of the First

World War, Duchamp based his philosophy on the singularity of the individual (everything else was a matter of Cartesian doubt)

and disengagement from politics, which he pronounced ‘a stupid activity that leads to nothing.’ But Dada‘s

critique of society probed far deeper. It was not only the political and military cadres that it targeted. Dada had not exonerated

high culture in its capacity as propagandist adjunct to the senseless carnage. Duchamp’s Readymades can be seen as part

of the affray against the art world’s pretensions of superiority and high mindedness; nor were the sciences exempt.

If part of Duchamp’s aim was to discredit science and technology and their positivist goal to measure and control nature,

and there is evidence that this was the case, then this may well constitute one of the many leitmotifs of the Large Glass,

the bachelors in the lower half frustrated in their efforts to possess the bride who represents nature’s blossoming

in the upper half. But nowhere is this better demonstrated than in Three Standard Stoppages (1913-14). What makes this

beautifully crafted work that questions the universal validity of scientific laws, in this case the French standard metre,

doubly ironic is its adoption of a mechanical engineering drawing style which was also used to depict the chocolate grinder

in The Large Glass. Based on dropping three one metre lengths of string on to a canvas from the height of one

metre Duchamp made three rulers conforming to the shape they took as they fell and then meticulously boxed them as if they

were technical instruments. Referred to by Duchamp as ‘the meter diminished’, the stoppages were consequently

used to calibrate the positions of the bachelors in The Large Glass. This was but one of the ways chance entered into

the making of this extraordinary work which is the lynch pin of the exhibition.

Echoing the subdivision

of the Large Glass, the exhibition is divided into two sections. It opens with Duchamp’s notorious painting Nude

Descending a Staircase and Bride, the latter painted in 1912 in Munich as a prequel to the Large Glass. The

image of the bride or ‘pendu femelle,’ (the female equivalent of the Hanged Man in Tarot) would eventually be

relocated in the upper sector of The Large Glass. This strange meta-mechanistic figure which has often prompted, I

think, ungrounded accusations of misogyny is both the object of the bachelors’ desires and the cause of their continual

frustration restricted as they are to grinding their chocolate in the lower section of the work. Rauschenberg and Johns would

have seen the original shattered version when they went to see Arensberg’s collection of Duchamp’s art works in

the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 1958. And just as John Cage prompted by Duchamp’s Readymades began to realise that

every sound could be music and Merce Cunningham recognised that any ordinary movement – walking, jumping or falling

– could be transformed into dance so Rauschenberg and Johns realised that ordinary objects could be commandeered to

become art.

|

| Dancers perform Merce Cunningham's choreography in the exhibition The Bride and the Bachelors |

It was a seismic shift in thinking and one that

meant that they shared a common understanding of the need to break with the romantic intensity and introspection of Abstract

Expressionism and instead enter into conversation with the everyday world, including its unpredictability, notably by using

impersonal techniques that purported to eliminate taste based on the individual artist’s active likes and dislikes.

Duchamp thus gave them leave to reject Greenberg’s narrow formalism and its insistence on a strict hierarchy between

high art and popular culture and the separation of media. Instead detachment and cool indifference to the painter’s

touch that had previously been sacrosanct opened up a space for found objects and readymade materials that aimed to remove

redundant barriers between artists, audience and art. In this way the problem of pictorial illusionism was rejected, Rauschenberg

commenting that ‘a picture is more like the real world when it’s made out of the real world.’

At different stages of their

careers Rauschenberg and Johns each independently collaborated with Merce Cunningham’s dance company and his musical

director John Cage. John Cage (1912-1992) had started out as a student of musical composition with Schonberg whose atonal

scores and the restriction he imposed on harmonic melody revolutionised modernist music. However by 1945 Cage, aware that

he was not successfully communicating with his audience, changed track and decided to concentrate on making his audience more

receptive to all the auditory elements, including non musical sounds and noise that naturally surround us. His study of Zen

Buddhism may have been a primary factor in this turn around but equally important was his friendship with Duchamp whose Readymades

announced that anything could become in Duchamp’s own words ‘a work of art without an artist to make it.’

However unlikely it may seem with Duchamp still a leading figure of the anti-art avant garde, what these two influences

had in common was an emphasis on an absence of emotion, or rather the search for a state of quietude or tranquillity of spirit

that the Greeks named ataraxia. Another common factor was the importance of the principle of chance and an emphasis on silence

that first came to the public’s notice with the performance of Cage’s piece for piano, 4’33”, which

required the pianist to lift the lid of the piano but then desist from playing. The idea was to attune the audience to the

ambient noise around them. Like Duchamp’s Readymades, which paradoxically needed the context of art institutions to

give them artistic status, Cage’s musical score needed the context of the concert hall for the sounds it framed to be

perceived as music.

|

| The Bride and the Bachelors Installation View |

Merce Cunningham (1919-2009) started his career as a dancer

in Martha Graham’s dance company but Merce Cunningham (1919-2009) started

his career as a dancer in Martha

Graham’s company but rejected her emphasis on dance as an allegory of inner

emotions. He wanted to free dance from narrative and make it co-exist but not

be dependent on music. Inner emotions were to come directly from the body as a physical

entity in its own right. Cunningham used

the dancer’s body as a found object, appropriating chance in order to

deconstruct habitual movement - he threw

dice to see how many dancers he was going to use on a particular performance - and

to bring not only the body but the whole person into play by stressing the physicality

of dance. With no story, no focal point and no hierarchy of position Cunningham’s

dancers used the stage as an energy field asking the audience to be aware of several

events at one time, a phenomenon Cage called ‘polyattentiveness’. Collaboration

between Cunningham and Cage had already started in the late forties when both

were visiting Black Mountain College. It was here too in 1952 that Cage’s legendary

Theatre Piece took place. Rauschenberg’s

White Paintings painted the previous

year were used as props while Cage sat on a ladder reading aloud about the

relationship between Zen Buddhism and music, Cunningham danced in and around

the audience, and everyone did whatever they felt inspired to do. For about ten

years Rauschenberg was artistic advisor to the dance company and in the sixties

Johns designed the sets for Cunningham’s Walkabout

Time directly basing them on the Large

Glass; these can now be seen suspended as inflatables over the central stage

at the Barbican which is surrounded on one side by Rauschenberg’s cavalcade of

bicycle wheels in homage to Duchamp.

By this time Johns’s monochrome grey paintings had themselves become increasingly

theatrical but also increasingly cryptic with everyday objects, brooms, cups,

rulers, thermometers, etc., affixed to them. They seem to insist on their hand-madeness

and induce a reflection on the nature of painting, or sculpture for that

matter. His Painted Bronze, for instance which reproduces two Ballantine ale cans

both supports and inverts the principle of the Readymade by insisting on a

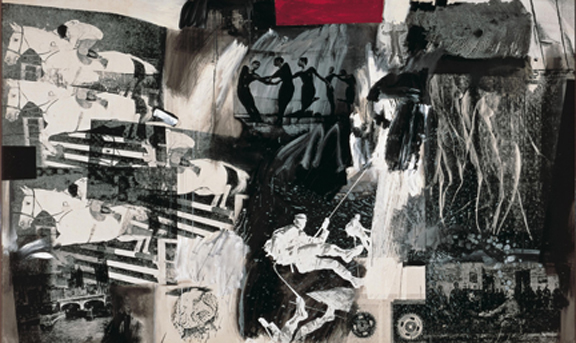

hand-crafted look. Rauschenberg, on the other hand, who was the extravert to

Johns’s introvert, recognised the artist’s role as recorder of the world around

him and worked in what he called ’the gap between art and life’ creating mixed

media, multidimensional environments from flotsam and jetsam, and silkscreen

prints, such as Express, with its

photographic image of Merce Cunningham’s dancers, from the proliferation of media photographs steadily engulfing capitalist

consumer society.

The themed sections on the upper floor of the exhibition (randomness and

chance, silence and negation, presence and absence, Duchamp’s fascination with

chess and other acrostic games and the blurring of life and art) demonstrate

how each artist developed a particular aspect of the Duchampian tradition and

made it their own. Whether Duchamp’s notion of chance is the same as

Rauschenberg’s or Johns’s is a matter of conjecture but there is no doubt that

the Duchamp phenomenon occasioned a particularly fruitful dialogue between the four

artists though often taking them in different directions. The cross-fertilisation

of cultural spheres, for instance visual with auditory, as in Rauschenberg’s Musical Box, which was originally

meant

to be shaken and was in all probability inspired by Duchamp’s sculpture With Hidden Noise (1916), can be seen

as

part of a Duchampian playful transgression of aesthetic boundaries. Johns, on

the other hand, concealed musical boxes behind his canvases which on the whole

are much more impenetrable and yet perhaps more revelatory of his personal

feelings.

|

| Robert Rauchenberg, Express 1963 |

Rauschenberg incorporated used found object and images onto his canvases

and his three-dimensional sets for Cunningham have a carnivalesque celebratory

quality about them. He used whatever came up in the course of his day to make

his Combine Paintings, which constitute unruly Readymades stitched together

with abstract expressionist flourishes of paint or other materials. Johns, on the other hand, is far more cryptic

and cerebral. The structure and shape of his canvases tend to be determined by

the choice of objects, images or systems he chooses to make the subject matter

of his canvases. These are made up not only from mundane objects but from two-dimensional

signs such as letters, maps and numbers which already belong to an abstract and

conventionalised realm of conceptualisation. These ‘things the mind already knows’

perplex not only because what was originally taken for granted becomes strange -

a familiar modernist trope – but because his sensuous handling of paint

reconnects him to the Abstract Expressionist tradition and seems to contradict

their communicative status. Moreover, the

fact that his motifs are simple, and often camouflaged, does not reassure but,

like Magritte’s paintings, confers on them a philosophical aura. It is as if

the artist knows something but withholds that knowledge – a feeling that often thwarts

interpretation in the viewing of Duchamp’s art works despite his championing of

the viewer’s share. One of the most memorable of Johns’s works in this respect

is a painting called NO that is made

up of a mottled field of grey on to which Johns has attached a long wire from

which dangles an N and an O made out of lead. These cast a shadow onto the

surface of the canvas and seem to refer back to Duchamp’s etching NON from 1959;

silence as an instrument of refusal.

John Cage was possibly the artist who shared most with Duchamp. His

systematic use of chance and randomness was closest to Duchamp’s in that its

prime motivation was to minimise his own personal choices by basing his artistic

decisions on the I Ching, the ancient Chinese book of divination. His series of

Strings was produced randomly by

dropping different lengths of paint soaked strings on to paper, much like the

way Duchamp had set up his Three

Stoppages. And though I’m no chess player and sadly lacking in a musical

education there is a playful delicacy about Cage’s scores and his acrostic

homage to Duchamp that echoes that of his friend. It is a lightness of touch that

you will also hear in Cage’s pre-recorded pieces for piano that resound through

the gallery together with recordings of birds, traffic, etc. and encourage the

viewer to interact and engage with the works on display in a completely novel ‘polyattentive’

way. Cage’s interest in Zen Buddhism encouraged a search for a detachment from

emotion that was essentially healing and an artistic practice based on letting

go and letting be that respects the world as it is without the need to radically

change it, though it could be argued that with reference to the art world, this

is precisely what Cage and Duchamp did.

This is an exhibition like no other. A sixth but invisible artist,

Philippe Parreno, is responsible for weaving all these disparate elements

together. He has created a mise en scene with pre-recorded Cage scores played

on ‘assisted’ pianos and devised a ghost performance on the stage that has

prime position at the centre of the exhibition space. And if you are lucky to be there on one of

days when a Cunningham event is scheduled you will see two or four dancers perform

excerpts from Cunningham’s choreography which add an extra dimension to the

whole exhibition. Meanwhile, Duchamp’s presence is still very much with us. We continue to live in the penumbra

that his challenge

bequeathed to the art world by problematising the boundaries we draw between

art and non-art and producing a range of meanings within these art/life

parameters that is a form of thinking about art. Yet it is interesting that those

closest to Duchamp insisted that while they did not necessarily understand his

art he taught them how to live well. Silence has divergent meanings embracing

plenitude and emptiness, openness and negation which depend to a large extent

on the viewer. But if these four artists tended to disclaim their own authorship,

we can now also turn to the political and social context to help us understand

this need for self-censorship.

Anna

Leung is a London-based artist and educator now semi-retired

from teaching at Birkbeck

College

but taking occasional

informal groups to current art

exhibitions. The Bride and the Bachelors is at The Barbican in London from 14 February - 9 June 2013.

|