|

The sunny days of summer

have long occupied a special place in American popular song. “In the Good Old Summer Time,” a Tin Pan Alley hit

of 1903, celebrated summer as a time of play, romance, and beautiful weather. However, the lyrics make clear that the song

is not addressed to a listener assumed to be on vacation: When your day's work is over

Then

you are in clover,

And life is one beautiful rhyme. . . . In this song, summer offers no respite

from the workaday world though it does complement labor by offering particularly enjoyable leisure-time activities. It was

introduced in a musical revue where audiences were encouraged to sing along with the chorus. A contemporary commentator, Charles

Belmont Davis, writing in the pages of Outing: The Illustrated Magazine of Sport, Travel, Adventure and Country Life,

found irony in the song’s relationship to an audience still chained to their desks: To me there was something

pathetically comic in rows of stout men sitting in a hot theatre, the perspiration running down their faces, all singing at

the top of their voices about the good old summer time. The chances are that the next day the gentlemen spent ten hours in

a hot office with a fan and a seersucker coat; but when night came around, there they were again, joining together in that

pćon of praise to the good old summer time. A half-century later, everything was different. The

American summer was no longer simply part of the work year but became the playground of children and teenagers released from

school and families who hit the road for extended vacations. The developments that intervened between “In the Good Old

Summer Time” and “Summertime Blues” included compulsory education, the ever-growing popularity of the automobile

as a means of middle-class transportation, and the development of the Interstate Highway system envisioned in the 1930s and

‘40s and brought to fruition in the 1950s. In the early 19th century, attending school had been voluntary and most children

simply didn’t go or didn’t go for long. Following on Horace Mann’s introduction of educational concepts

imported from Prussia, many American states enacted compulsory education laws beginning in the mid-19th century. Mann also

argued for a standardized nine-month school year calendar that left the summer months free. Thanks to these reforms, summer

came to be defined officially as a time of leisure, at least for school-age children and their families. Thanks to the automobile

and the Interstates, families had somewhere to go on their summer vacations and the ability to get there.

The automobile also contributed

to another crucial social development, sometimes called “The Invention of the American Teenager.” In 1903, you

were either a child or an adult: there was no middle term that designated adolescence as a unique phase of the life cycle.

Although adolescents began to be recognized as a distinctive social group and market as early as the 1920s and 1930s (which

is also when terms like “teen-aged” first emerged), teenagers really came into their own following World War II.

Because of compulsory education laws, the populations of high schools increased substantially, giving teenagers greater social

contact with one another, and the declining cost of owning and operating an automobile gave young people significantly greater

mobility. Both were important factors in the emergence of teenagers as a group with its own sense of identity that it wished

to affirm through cultural consumption. In the 1950s, teenagers were estimated to constitute a $7 billion market for music,

fashion, movies, television shows, portable radios, and all manner of consumer goods. Most of the popular songs about summer to appear from the mid-1950s on were directed

to this new audience and reflected the rhythms and concerns of teenaged lives, not those of the tired office worker facing

the prospect of returning to the grind in the morning. The songs of summers after World War II were addressed largely to an

audience of young people who, even if they were working summer jobs, felt genuinely liberated because summer meant they were

out of school and away from their parents (at least some of the time) for several months—they did not have to return

to their version of the grind until the fall. It may seem, for example, that the Beach Boys’ “Surfin’ USA”

(1963) is about surfing. Actually, it’s about the burning desire to get out of school in order to be able to surf: “We’re

waxing down our surfboards/We can’t wait for June.” Come June, not only will the surfers be able to hit the beaches

fulltime, their teachers will no longer have authority over them. They can call their own shots: “Tell the teacher we’re

surfin’/Surfin’ USA.” “Gone Surfin’” is the teenaged equivalent of “Gone Fishin’”—a

refusal of quotidian responsibility and routine (as expressed in song for a previous generation by Bing Crosby and Louis Armstrong

in 1951) and a demand to do one’s own thing.

One of the key themes of

teen-aged life as depicted in postwar popular culture is resentment of authority as represented by parents and teachers and

the desire for autonomy. This attitude is clearly reflected in rock and roll, including Chuck Berry’s 1957 classic “School

Days.” The life of Berry’s high schooler is not significantly different from that of a nine-to-fiver: the teenager’s

life is regimented by the alarm clock and the school bell. School itself is pure drudgery, an exhausting routine of putting

up with the demands of unkind teachers and “working your fingers right down to the bone.” But, “As soon

as three o’clock rolls around/You finally lay your burden down.” Being released from school can mean only one

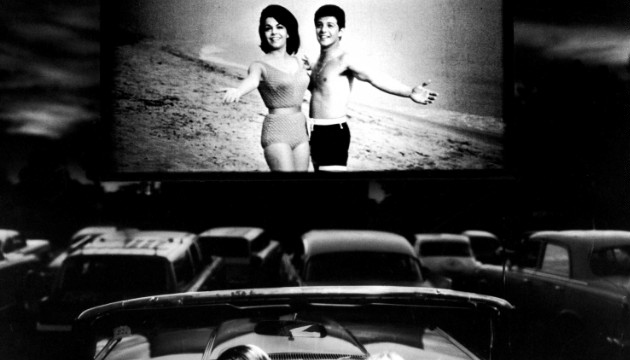

thing: a trip to the juke joint to dance and romance. While set in a malt shop rather than a juke joint, the opening moments

of the movie Rock, Rock, Rock (1956) offer an identical scenario as teenagers, still carrying books, flood into the

local joint immediately after school to hang out, listen to the big beat, and dance. The great thing about the last day of the school year is that you don’t

have to go back the next day: you can hit the juke joint, the malt shop, the beach, the drag races, wherever your leisure-time

muse leads you without having to worry about school, at least until after Labor Day. No song better expresses the sense of

release attendant on the official beginning of summer than The Jamies’ 1958 “Summertime Summertime,” a vocal

group exhortation to “shut them books and throw 'em away/And say goodbye to dull school days,” tell the teacher

to “zip your lip,” and plunge headlong into summer activities: Well we'll go swimmin'

every day

No time to work just time to play

If your folks complain just say,

"It's summertime" Sly and The Family Stone’s much later “Hot

Fun in the Summertime” (1969) takes up a similar theme, albeit with a different catalog of summertime activities and

in a very different style with a much less frenetic, more laid-back tone. Alice Cooper’s “School’s Out”

(1972) is a pure, violent expression of the urgency with which teenagers feel summer coming on and the desire to be done with

school.

To listen to an excerpt from The Jamies' "Summertime Summertime,"

please click on this player:

|

| Sly and the Family Stone |

The British anthropologist Victor Turner developed the concept of liminality to describe

a feature of the lives of both societies and individuals. The word “limin” means threshold, and liminal phases

are times when people or groups find themselves “betwixt and between the positions assigned and arrayed by law, custom,

convention, and ceremonial.” To be a teenager, no longer a child but not yet an adult, is to pass through a liminal

phase of the life cycle in which one can no longer claim the innocence of youth but also cannot be held to all the responsibilities

of adulthood. Over the years between the mid-19th century and the mid-20th century, summer in the United States became increasingly

defined as a liminal season, particularly for young people, a time of year when teenagers were released from the routine and

discipline of school, relatively immune from parental authority, and thus more autonomous than at other times. As The Jamies

put it, summer is “a regular free for all.” The song “Summertime Blues,” co-written and recorded by

Eddie Cochran, whose version came out in 1958, became a rock classic (recorded variously by Blue Cheer, The Beach Boys, The

Who, T. Rex, and Joan Jett, among others) largely on the strength of its infectious rhythm guitar riff, but also because it

acknowledges the liminal character of the teenager’s summer by suggesting that the encroachment on the protagonist’s

freedom by his parents and boss is a crime worthy of investigation by Congress and the United Nations. Such figures may rightfully

exert their authority during the school year, but not during the summer. To listen to an excerpt from Eddie Cochran's "Summertime Blues," please click on this player: Precisely because they entail the relaxation of the usual rules and assumptions that govern

quotidian life, liminal periods can result in positive change, such as the beginning of the romance chronicled in The Danleers’

doo wop classic “One Summer Night” (1958). By the same token, however, it is always risky to enter into a liminal

condition. Both the joys and dangers of liminality are often figured in popular songs in relation to romance. On the one hand,

since “Summer Means New Love” (the title of a Beach Boys instrumental) the seeking out of summer romance is almost

obligatory. But the sad truth is that summer romances often end come Labor Day, when it turns out that feelings expressed

during the summer do not carry over into the rest of the year. The doo wop counterweight to a song such as “One Summer

Night” is The Earls’ “Remember Then” of 1962 whose protagonist reflects back on a relationship that

began, like the one in the Danleers’ song, on “a lovely summer night” but did not outlast the season: “Summer’s

over/Our love is over.” To

listen to an excerpt from The Earls' "Remember Then," please click on this player:

The Beach Boys are famous for having created through their music a teenage utopia, an Endless

Summer of surfing, cruising, dating, racing cars, riding scooters, dancing, going to theme parks, and hanging out; two of

their best early albums are 1965’s Summer Days (and Summer Nights) and All Summer Long of 1964. But Brian

Wilson, the primary writer of the group’s songs, was also acutely aware of the fragility of summer relationships and

the heartache attendant on them. “Girl Don’t Tell Me” is a boy’s bitter rejoinder to a summer love

who’d told him she’d write to him during the school year, but didn’t—the opening lines are “Hi

little girl, it’s me/Don’t you know who I am?” He cynically resolves to treat the relationship for what

it clearly is to her: “I'll see you this summer/And forget you when I go back to school.” An earlier Beach Boys

song remarkable for its poignancy and emotional ambiguity is “Keep an Eye on Summer” (1964) in which the male

protagonist would like nothing more than to rekindle a relationship that ended in the fall and that he has tried to sustain

by writing letters, while also understanding that the odds are against this. The refrain “Keep an eye on summer”

seems to point to the only time the lovers have any chance of being together again. To hear an excerpt from The Beach Boys' "Girl Don't Tell Me," please click

on this player: Just as the end of summer can sound the death knell for seasonal

romances, so can the summer be a threat to school-year relationships. “See You in September,” a hit for The Tempos

in 1959 and an even bigger hit for The Happenings in 1966, expresses the protagonist’s fear that the girl whose parents

are taking her off for a summer vacation will find another while she’s away. Although the song’s title sounds

affirmative, it is much more tentative and plaintive in the song’s lyrics: “Will I see you in September? Or lose

you to a summer love?” A noteworthy exception to the portrayal of summer as the Death Valley of relationships is “Summer

Rain,” a hit for Johnny Rivers in 1968, in which a summer romance has seemingly mellowed a year later into something

likely to last. The song is redolent of adult contentment and complacency rather than the teenaged energy and anxiety expressed

in so many summer songs. To

hear an excerpt from The Happenings' "See You in September," please click on this player:

Even if summer turns out to be everything it should be, sun and fun, no summertime blues,

no romantic heartbreak, its status as a liminal period means that it is necessarily temporary. As Turner points out, liminal

states can be attractive and people may seek to prolong or even institutionalize them. But in the case of summer, this cannot

be. There is no Endless Summer after all; school is not out forever; we cannot be “on safari to stay.” The inexorable

law of teenaged life as reflected in popular music is that summer begins on the last day of school in June and ends in September

when school resumes and parents and teachers reassume their authoritarian positions. For this reason, songs about the pleasures

of summer are often tinted with melancholy, for the knowledge that the obligations and restrictions that come with fall and

the new school year are just around the corner necessarily dampens the joy of the season. Despite its upbeat sound, bouncy

rhythm, and jaunty whistling section, The Beach Boys’ “All Summer Long” conveys these mixed emotions. The

refrain “We’ve been having fun all summer long” is undercut by “Won’t be long till summer time

is through.” The notion that the teenaged couple in the song is facing the imminent end of liberty is stated directly:

“All summer long, we've both been free/Won't be long 'til summer time is through.” Or maybe not. One song by the Beach Boys suggests

that it is possible to keep the spirit of summer alive even during the school year. The car-obsessed teenaged girl described

in “Fun Fun Fun” (1963) has run afoul of authority: she lied to her father about going to the library and cruised

the hamburger stand instead. In retaliation, the father predictably revoked her driving privileges, seemingly clipping her

wings. But the song’s male narrator, while paying lip-service to authority (“you shouldn’t have lied”)

also suggests that daddy’s having taken the T-Bird away opens up opportunities rather than shutting them down, that

through teen-aged resourcefulness it is possible to create a liminal space of freedom even under the watchful eyes of the

school-year authorities. Like all liminal conditions, like summer itself, it is fragile and may well prove to be temporary.

But for the moment, the Beach Boys’ soaring vocal harmonies proclaim, “we’ll have fun fun fun now

that daddy took the T-Bird away.” To hear an excerpt from The Beach Boys' "Fun Fun Fun," please click on this player:

|