|

|

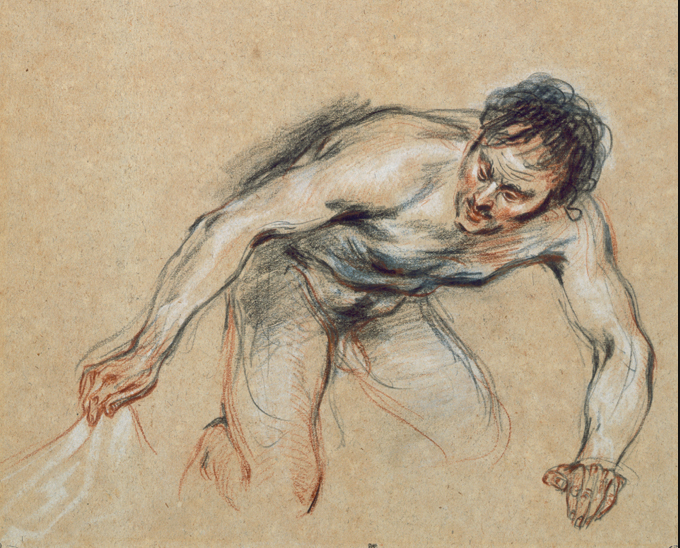

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Studies of Actors, a Pair of Hands and a Fragment of an Arabesque (c.1711). Photo © Hessisches Landesmuseum, Darmstadt.

Watteau’s Drawings: Virtuosity and Delight at the Royal Academy

By Anna Leung

Antoine Watteau died in 1721 at 37, the same

age at which Raphael died. Two years earlier he had travelled to London to

consult with Richard Mead, a highly reputable doctor and an admirer of his

work. As well as searching for a remedy for his tubercular condition he may

well have thought to rescue his finances. Like many others in France, where

Louis XV had adopted the Scotsman John Law’s economic system in order to

stimulate an economy worn down by the successive military adventures of his

predecessor, the Sun King Louis Quatorze, Watteau had been caught up in the

failure of Law’s speculative financial system that, culminating in the

Mississippi Bubble, was the first casualty of boom and bust economics based not

on gold but on paper credit in the emerging modern period.

Indeed what strikes us as we wander through

this exhibition is the modern feel imparted by Watteau’s sketches, which he

suggestively referred to as his ‘pensees a la sanguine’ [Editor’s Note: This phrase should

be translated in this context as ‘thoughts in red chalk,’ though it could also

mean ‘bloody thoughts’]. At the same time as they capture a world of social

encounters they also reveal an interior world that belongs exclusively to

Watteau. Interestingly this quite

probably would not have seemed to be the case were we to have first encountered

Watteau’s paintings at a separate companion exhibition at the Wallace

Collection. Contrasted with Watteau's highly decorative

paintings in

which he excels in translating silk and textile into paint, his drawings have

an intimacy and an interiority that is modern. The drawings and paintings seem

to present very different facets of Watteau's character. Perhaps less elegiac

the drawings probe more deeply into the human condition and suggest a universal

correspondence that transcends social and cultural differences.

A whole new genre, the ‘Fetes Galantes’, had to be invented by the Academy in order to

legitimise and make comprehensible his wayward paintings – since they seemed to

be about nothing, i.e. did not have a subject that fitted in with the normal

genre classifications. As we shall see Watteau epitomised a new vision that

prefigures elements of the modern. Being recognised as a member of the Academy

obviously did not preoccupy Watteau unduly, for it took several years before he

was able or wanted to present his obligatory reception piece Pilgrimage

to

the Isle of Cythera

in 1717, and

though eventually accepted he never became an Academy man. This lack of

enthusiasm on his part may be traced to the fact that earlier, in 1709, he had

only won the second place in the Prix de Rome competition, thereby forfeiting

the possibility of becoming much more of a main stream academic artist by studying renaissance and baroque masters in

situ

in Italy. But Watteau was from the beginning marked out by birth and class to

take on the role of a proto-modern outsider.

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Nude Man Kneeling, Holding some Fabrics in his Right Hand (c.1715-16). Musée du Louvre, Paris. Photo © RMN / Thierry Le

Mage.

His

Life

Born in Valenciennes in 1684 Watteau was Flemish

rather than French, for Valenciennes had only just been annexed to France in

1678. This in itself would have contributed to his outsider status, since

French was not his mother tongue and he may have spoken

with a distinct Flemish accent.

Moreover his background was working class; his father was a roofer and tiller.

But by 1702 he was in Paris working first under Gillot, a contemporary artist

specialising in theatrical costume and scenes from the commedia

dell’arte (which was

banned in 1697), and then

with a reputable interior decorator, Claude Audran, who also happened to be the

curator of the Palais de Luxembourg. Here Watteau would come into close contact

with Rubens’s series of paintings on the life of Marie

de Medicis, 1624, an important

source of

inspiration for him, as were Titian’s paintings. Throughout his short life

Watteau remained a highly independent artist, though he was dependent on the

good offices of his many loyal friends as he moved from one household to

another. He never married, was well read and loved music above all. Many of his

drawings depict musicians.

This independence applies to his art practice.

Bound by neither state nor church, his new genre of painting coincided with the

growing affluence of the bourgeoisie whose prominence had been abetted by Louis

XIV’s appointing them to administrative positions in an effort to curb the

power of the nobility. A new mercantile space opens up, and art becomes a

luxury good no longer bound by the wishes of aristocratic patrons but offered

for sale to anonymous buyers--a new public that reflects the democratisation of

the arts. Up till this time in France, works of fine art had remained within

the purview of the Academy, which sequestered them from commodification or

commerce, viewing these as vulgar. Watteau was never part of this patronage

system, and though he was supported by wealthy individuals, it was not their

taste that determined his choice of subjects. We can glimpse here the beginnings

of a contradiction that comes to define the 18th century. On one

hand there is the emergence of a concept of aesthetics, on the other the

increasing commodification of the art work. If the Kantian experience of beauty

is based on ‘disinterested pleasure’, art’s autonomy viewed under the aegis of

ethics, Watteau’s paintings lure us in with a highly interested (and even

erotic) content. Watteau holds desire and aesthetic pleasure together for a

short period. This seems to apply to his paintings, but does it apply in equal

measure to his drawings?

Transition

- the Regency

It is significant that Watteau’s artistic

career spans the period of decline and dissolution of the Sun King’s absolutist

power. That his power had been vested in his actual presence, and his body

conflated with the body politic of France, is apparent from such court rituals

as the King’s levee, etc. The war of the Spanish Succession, begun in 1701, was

disastrous and exacerbated an already existing economic crisis brought on by

unwise military ventures that resulted in the increase of unjust taxes, the

debasement of coinage, a spate of natural disasters and repeated bad harvests.

Finally the king suffered a personal tragedy in the death of his son, grandson

and eldest great grandson; under the influence of a bigoted puritan wife he

grew increasingly pious and intolerant. All distractions at the court were

banished. As a result the courtiers, who had been to that point virtually

prisoners in a gilded cage in which all sense of self was totally subservient

to the monarch’s will, began to take flight from Versailles and set up alternative

courts in Paris and its environs.

By the time the Regent, the Duc d’Orleans, who was to rule till Louis XV

came of age in 1723, took up the reins of power after Louis XIV passed away in

1715, the courtiers, till then bound by strict protocol that demanded an

inflexible form of etiquette, had fled from Versailles to the countryside

around Paris, adopting the hedonistic life style Watteau captured in his Fetes

Galantes. These

intimate paintings were destined for intimate spaces given over to comfort

rather than the coldly opulent splendour of Versailles.

More than any other artist,

Watteau embodied the transition that made way for the increasing

commodification of the art work and with it a new public that gained in

strength over the eighteenth century. His paintings are the polar opposites of

the rational clarity demanded by an absolute ruler. The paintings of the Fetes

Galantes are not simply figments of

the artist’s imagination but reflect an attempt made by members of the

aristocracy to create their own private centres of power. Donning theatrical

costume, they continued to enact their social roles but according to a different scenario framed

by the arbitrary rules of love and chance that were based not on emblems of

power but on a newly discovered sense of subjective inner worth. In the Fetes

Galantes the protagonists play a

coded game regulated by the flicker of an eyelash or the opening or closing of

a fan. These are no longer edifying history paintings that demand of the artist

that the message is be totally

comprehensible with no room for equivocation or doubt. Watteau’s paintings

suggest multiple and ambiguous readings, especially when his figures resemble commedia

dell’arte players, and even statues

seem decidedly human and alive. No rational narrative, but rather an atmosphere

of sensuous reverie is set up. Surrounded by an unkempt nature now no longer

subjected to the rigid principles of geometric topiary, Watteau’s congregation

of characters disport themselves in accord with the rulings of a whimsical god

of love. It seems to have been Watteau’s landscapes that won the admiration of

his contemporaries. Significantly, it is precisely this aspect that is absent

from his drawings, in which he concentrates

on the figure and leaves context to our imaginations, which is already a very

modern procedure. While

they constitute a catalogue of characters for his paintings, Watteau’s drawings

exemplify a new concept of the aesthetic that, particularly because of his

ability to capture the transience of a moment, is a true forerunner of modernism.

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Woman

Seen from the Back Seated on the Ground, Leaning Forward (c.1717-18). Photo © The Trustees of the British Museum, London.

The

Drawings

It is the realism, rather than make-believe, of

the drawings on display in the Sackler Wing realism that distinguishes them

from academic drawings based on classical models. Watteau is dealing with

ordinary people, not rhetorical ciphers whose facial expressions were subject

to academic codification. Much scholarship has gone into relating figure

drawings from Watteau’s sketch books to his paintings, and in some cases the

curator has furnished us with the relevant reproductions. But the fact that the

same figure or its mirror image is used more than once makes for difficulties.

And when it comes to the matter of aesthetic valuation Watteau, it is recorded,

saw himself as a greater draughtsman than painter. Posterity seems to have

agreed, so that his drawings continue to be highly valued for their own sake.

His paintings, on the other hand, have suffered over the years – it seems that

his painting techniques left much to be desired. Consequently, they have not

weathered well, while most of his drawings still retain their freshness and

have lost little

of their charm and delicacy of touch.

Technique

Watteau was not the first artist to use red

chalk or even the three colour system for which he is famed. Leonardo is

credited with the first use of red chalk, or sanguine, which derives its name

by association with the colour of blood. Popular in the renaissance in the use

of figure studies, its best known exponent was Michelangelo. The red chalk that

comes in the form of short sticks that can be sharpened was made of hematite

(iron) and clay in a wide range of tones and shades. As we see from these

drawings, it can be used in a variety of ways. Stumped with a rag, it creates

volume and

lightens in colour; when dampened, it becomes darker; and sharpened, it can

produce the most ephemeral and delicate of touches. Rubens, one of Watteau’s

favourite artists, was a great exponent of this material and Watteau made

copies from his sanguine drawings. Watteau started out using just the various

tones of red and gradually extended his practice to different blacks, including

graphite, and white, and was able to suggest a whole panoply of colour when

using all three. Because Watteau did not date his work, it is difficult to

gauge when he began to use all three colours, but the magistral portraits of

the Persians and Savoyards inclines us to think it must have been around 1715

when a Persian delegation came to court and stayed about six months. In both

cases, Watteau used black over red to accent a particular area, as in the hair

of the Young Savoyard holding an Oboe with a Marmot Case slung across his

Shoulder, c. 1715,

or to summon up a shadow. He used white mainly for highlights or to suggest the

delicate sheen of skin, but in the case of the three studies of the black boy

in Studies of Eight Heads, c. 1715-16, he used it to accentuate the area around their heads so that they stand

out from the page. Watteau restricted himself to these techniques, only very

seldom adding a pale wash. Often it is impossible to tell which colour has been

applied first. As his expertise increased, his figures or portraits tended to

increase in size, taking up more of the space on each sheet, but it is again

difficult to tell since he often added figures to existing sketches so that the

images on a single page may belong to different periods.

Life and/or

Theatre

One of the most salient aspects of Watteau’s drawings

is the absence of setting. His figures sit on invisible chairs, kneel against

invisible steps, or lean against invisible fountains or balustrades. There are

very few in which Watteau has sketched in a background. In marked contrast to

academic drawings, his figure studies are not of types that impose on the

viewer a specific code of conduct. Instead, he attempts to capture the real

life presence of ordinary people from all ranks of life, from Persian

dignitaries to young shoeshine boys. In this he is close in spirit to the

Enlightenment project. But he does not classify them according to their work.

His soldiers, for instance, are not depicted in the thick of battle but rather

off duty, relaxing or recovering from battles. His courtiers, actors and

musicians may be rehearsing rather than performing. It is this crucial

difference that is a feature of the aesthetic and beguiles us into trying to

make a distinction between real life and art within the realm of performance

and artifice which reveals as much as it conceals. That sincerity came to be

much prized in this period, and with it the importance attached to

subjectivity, is brought out in Watteau’s emphasis on the ordinariness of these

figures captured on the pages of his sketch book, which he then used to create

his paintings where they take on a very different life. As drawings, they

communicate a marvellous sense of empathy unusual at the time, though one that

comes to characterise the bourgeois centred art of Chardin and Boucher with

their emphasis on family life. There is, however, a new relationship of parity between artist and model--a mutual

respect that is totally devoid of the sentimentality that comes to characterise

Greuze.

Perhaps the very nature of drawings, their

seeming lack of permanence compared to paintings, lends them the very quality

of melancholy and gentle wistfulness that Watteau, who knew death was imminent,

was able to convey with reserve and mute tenderness. The kernel of what

Watteau’s drawings can impart to us is that beauty is the hostage of death, but

shines ever brighter in the knowledge of its ephemerality. They engage us with

their fluidity and with an acute awareness of things passing. Watteau has the

ability to transpose onto the page the moment of transition

that seems to precede a

movement or even the decision to move. However, the aesthetic dimension is

hardly ever lost, and though he seems to include drawings from different

periods on one and the same sheet he nearly always respects the whole page’s

aesthetic autonomy and in this respect, as in many others, is a forerunner of

the modern period. Watteau also knew that even if the artist

of his time had been liberated

from church and state, he was now subject to the impersonal forces of the

market.

© Anna Leung, April 2011

Anna Leung is a London-based artist and educator now semi-retired from teaching at Birkbeck College

but taking occasional informal groups to current art exhibitions. The exhibition Watteau: The Drawings is at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, and its companion exhibition, Esprit et Vérité: Watteau and His Circle, is at the Wallace Collection, London, from 12 March - 5 June 2011.

|

|

|