|

|

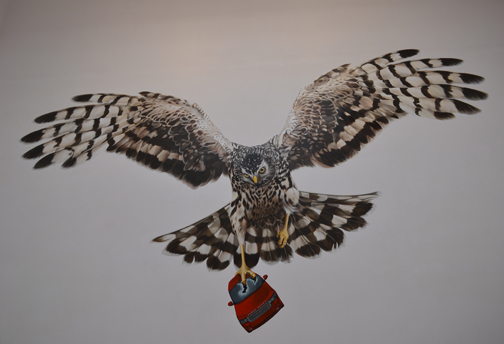

| Sarah Tynan, A Good Day for Cyclists, 2013. Photo: Evelyn Saleh. |

Jeremy Deller: English Magic

The British Pavilion at the 55th International Art

Exhibition la Biennale di Venezia

By Floriana Piqué

A Man of Many Talents Jeremy Deller, an educated art historian and an installation and

video artist, created across the rooms of the British Pavilion English Magic, a personal, unique history of England that shifts constantly between reality and magical

fiction. He combines, this time on a larger

scale, his usual ways of expression like video, music, installation, staged events, collections of memorabilia, art works

and contributions from other artists with his political and social passionate involvement. Jeremy Deller’s realization of the British Pavilion at this year’s Venice

Biennale is an example of his complexity as a personality and of his numerous interests as human being. A young man of his time, he looks to the Past to take inspiration for interpreting the

Present and imagining the Future. The Past is for

Deller not just the recent one, the one which affects his span of life but, quite unusually, the Prehistoric Age. Deller assembles and combines works, actions, thoughts of different

people, artists, and thinkers to conjure his own project. What results is a unique staged event that in a certain way blurs

the boundaries and explores the limits of the various disciplines implied. For this artist, the viewer’s participation is essential not just to the realization but mainly

to the existence of the work itself.

The Pavilion opens with a huge mural

painted by Sarah Tynan: a giant Hen Harrier, a rare bird of prey, spreads out its wings while crunching its talons through

the windscreen of an expensive four-wheel-drive SUV. The

spectator is mesmerized by the revenge of Nature over Mankind. At the same time the irony in the title, A Good Day for

Cyclists, relieves the strong aggression. This

is Deller’s way of showing his works and approaching life: balancing the impact of natural forces with the lightness

of irony. From the present day’s image

the artist moves us to our Paleolithic past. The Small Faces is a group of hand axes dated 250,000-400,000 B.C., a hint to

how far we can retrace the origins of English civilization. The

viewer is offered the opportunity to hold in his hands some of these tools to create a tactile bound with our Ancestors. A jump to a hypothetical future is on the third wall. In June

2017, after a demonstration of UK citizens angry over the Jersey Islands’ status as a tax haven and the secretive culture

of the banking system there, the capital St. Helier is set on fire. A large mural, St. Helier on fire 2017, painted

by Stuart Sam Hughes is a manifesto of Jeremy Deller’s social-political ideas. This political intention is even more evident inside this year’s Biennale where

the main exhibition The Encyclopedic Palace is connoted by a rich, sophisticated research stretched to the limits of eccentricity.

|

| Stuart Sam Hughes We Sit Starving Amidst Our Gold, 2013. Photo: The British Council. |

In Room 2 Deller presents the work and the

figure of William Morris, a Victorian artist, textile designer, writer and libertarian socialist, deliberately in contrast

with the way Russian capitalism unfolded after the crash of the communist regime. A mural covering an entire wall, We sit starving amidst our gold, painted by Stuart Sam Hughes, sees

Morris as the God of the Sea, a giant Poseidon throwing the huge yacht of the Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich into the Venetian

lagoon. Russian share certificates, coupons, and

privatization cheques are displayed on the adjacent wall, an immediate depiction of the way in which few built up an immense

fortune at the expense of many. In a Venice where,

during the Biennale, there are exhibitions in foundations linked to big corporations and extremely wealthy collectors, this

statement of Deller’s sounds like a very strong statement. Deller’s peculiar way of producing art, of acting as artist, curator, filmmaker, organizer, stage director

reflects back to his career. Born in 1966 in London,

in 1993 he organized his first exhibition, Open Bedroom,in his family home while his parents were on holiday. In 2001 Deller staged The Battle of Orgreave, a re-enactment of

the violent clash between miners and police during the 1984 strike at Orgreave, Yorkshire. This project, resulting in a filmed performance, engaged 1000 people, amongst them veteran

miners and members of historical societies. The recipient

of the Turner Prize in 2004, in 2012 Jeremy Deller saw his mid-career retrospective, Joy in People, at the Hayward Gallery,

London and in the same year realized Sacrilege, a life-size inflatable replica of Stonehenge, with the polemical intention

of rendering the historic site more accessible. In

the US the artist created Memory Bucket (2003), a documentary about Crawford, Texas, the hometown of George W. Bush,

and the siege in Waco; in 2009 his project It Is What It Is: Conversations About Iraq, was commissioned by the New Museum,

New York; the Hammer Museum, LA; and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago. After the Venice Biennale, Deller will curate a new Hayward Touring exhibition launching this autumn

at Manchester Art Gallery. All That Is Solid Melts Into Air is described on Artlyst.com as “a personal look at

the impact of the Industrial revolution on British popular culture and its persisting influence on our lives today.”

|

| Scott King, Bevan Tried to Change the Nation, 2013. Photo Evelyn Saleh. |

Across

two rooms in Venice Deller explores in his original way the recent history of

Britain with its tragic moments.

The

artist collected and now shows a series of drawings made by untrained amateurs,

some of whom are prisoners or ex-soldiers.

The

subjects of these drawings refer to the war in Iraq, with shocking scenes

of life in the Army and portraits of political figures of that period, amongst

them Tony Blair.

David

Bowie’s Ziggy Stardust tour of the UK, which started on 29 January 1972 and

lasted 18 months, marked a pivotal point in British Pop music and had an impact

on the culture and the social life of the young generation.

In

Room 6 Deller counterpoints images of the tour with pictures of tragic events that

happened on the same day, such as the Bloody Sunday of Londonderry, Northern

Ireland – 30 January 1972--other industrial actions, or the bombing campaign by

IRA.

Bevan tried to change the

nation is a

map drawn by Scott King that retraces the path of Bowie’s tour across the UK,

creating a hypothetical space. The character of Ziggy Stardust as alter-ego and

double-self created a virtual reality, a refuge from a troubled, difficult real

world in which an entire young audience could find an alternative existential

space.

Deller

chooses to dedicate an entire room of the Pavilion to create a tea-room

offering the opportunity to enjoy a real experience of an English tea. A

perfect English way to cope with problems, adversities, bad moments in life:

sit down and have a good cup of tea.

|

| Stuart Sam Hughes, St. Helier on fire 2017, 2013. Photo: The British Council. |

The film English Magic

that gives title to the Pavilion can be seen like a summa of Deller’s ideas. Birds of prey fly across the screen as a prologue and epilogue, a reminder of the strength

of Nature. The Melodians Steel Orchestra from

South London performs the sound track, recorded in Studio 2 at Abbey Road Studios in London. The three tracks – Excerpts

from Symphony No.5 in D, 3rd movement, Ralph Waughan Williams; Woodoo Ray, A Guy Called Gerald; The Man Who

Sold The World, David Bowie – produce an independent, quite hypnotic sound, a continuum opposing the fast cut of

the images and the succession of different subjects. Heavy

machines in a scrap yard ideally conclude the demolition work started by the Hen Harrier painted on the wall in Room 1. The magic of Stonehenge, the most famous Neolithic site, comes

back to life as a gigantic inflatable playground where a joyful crowd of children and adults jump and run. As Deller says:

“In this case I wanted to make a massive, absurd, surrealistic artwork that the public could go on and could engage

with and think about in many different ways. It was sending up the heritage and history of Britain, but only in a Monty Python

way, from a position of fondness. At the end of the day it was meant to be a tactile, enjoyable artwork” (interview

between the artist, Chris Dercon and John Paul Lynch, British Pavilion publication). Staged parades put together by real and fictional guilds, societies, groups of people:

scientific instruments makers, lightmongers, London Freemasons, chartered secretaries, soldiers, tax advisers. “Sometimes the public is the work. I work with people

as another artist might use paint – to work with them to express ideas is the most exciting and fulfilling thing, I

love that” ( interview with Ben Luke, Royal Academy Magazine, summer 2013). While in the other Rooms political and social issues prevail, here in this film we can

perceive a quite nostalgic sense of community and we feel that this is the real English Magic.

|