Features

|

|||||

Features |

|||||

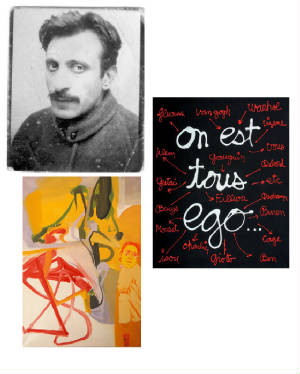

Artists who use language

in their artwork usually come from

a tradition of conceptual art. Long time Fluxus artist Ben Vautier, who is

known as Ben, uses text and language as his work. He currently has a

retrospective of his artworks at the MAC Lyon. Here, Ben will be rediscovered

by a new generation of artists, and I believe his influence will be profound.

His wit and irony are powerful. I think if Ben had been of a later generation

he would be a street artist scrawling his text on the sides of buildings and

under bridges. (Please Ben, that

was not a challenge or even a suggestion; I think you a great artist just as

you are.) In this issue of TAS, we have

Ben’s longtime friend Michel Batlle in conversation with him, two bad boy

artists enjoying their banter, as fresh as when it was originally published in

French. David Humphrey is also an artist who writes and who, you

could say, is also a bad boy. But his text takes the form of a book about art

rather than constituting the art itself, though he does see the two things as

closely connected as Alexi Worth, a fellow artist, observes in his introduction

to our selection from Humphrey’s book Blind Handshake, which

is a collection of essays that all take other people’s art as their starting

point. In this month’s TAS

you can hear, as well as read Humphrey’s essay

“Describable Beauty.” His paintings are delicious counterparts to his writing.

They can be seen at Sikkema Jenkins in New York City and Solomon Projects

in Atlanta. You can find his book on Amazon, but this you knew already. And I am happy to publish an essay by Anna Leung, also an

artist who has become an art writer, who writes about a very bad boy artist,

Ashille Gorky. Leung saw his magnificent retrospective at the Tate Modern; it

is now at LA MOCA through September 20, 2010. For me, he is a quintessential

twentieth-century artist, and his works speaks loudly and clearly to me every

time I see it. Welcome to the beginning of the 4th year of TAS. Best, Deanna

David Humphrey in the studio. Blind Handshake To stand next to David Humphrey at an opening is to hear

an accelerating fusillade of choice anecdotes, movies tie-ins, literary

allusions, and sly judgments, often prefaced with a laughing, personalized

invitation: “Wait—you are going to love this.” Humphrey’s art talk, in other words, is special—in

being

more ambitious, excitable, funny, and unapologetically book-fed than other

artists’. When Humphrey began writing, around 1990, Theory was king.

In New York, young artists either parroted the righteous pedantic ideas they

had skimmed in October magazine, or felt truculent and cowed. In the regular

column he began writing for LA’s Art issues, Humphrey set out to write the kind

of criticism he wanted to read. He would pick three shows, not necessarily the

ones he liked best, but ones from which he thought he could tease “a little

thematic arc.” Each column, in other words, would be both an idea talk and a

gallery walk. Above all, Humphrey wanted to keep in mind the way artists speak

in one another’s studios. During studio visits, pronouncements come last, if at

all. Typically, the visitor talks as he looks, cataloguing impressions, making

distinctions, parsing tone. The aim is to offer the host artist a kind of

constructive, synthesizing attentiveness. That’s the essence of Humphrey’s

writing. His

voice has the animated, collegial spirit of a studio visitor. He has a great,

greedy, omnivorous eye, and he loves registering what it sees. He moves eagerly

from general observations back to description. He quotes readily from whatever

he’s reading. His allusions feel impulsive—they are offered, not insisted upon.

A major hallmark of periodical criticism—the dutiful mapping out of influence,

debts, and stylistic affiliation—Humphrey largely avoids. An even bigger

omission: Humphrey doesn’t give grades. He simply drops the whole PR apparatus

of artworld status. You will never read him say that X is among the greatest

artists of his generation. Censure, the mainstay of nervous and cocksure

critics alike, is likewise absent. Only a few stray words, delivered with no

special emphasis, hint at what the writer might say if he were asked to buy,

say an Odd Nerdrum painting. In

Humphrey’s patience and flexibility, you can feel his freedom—the permission

given by the fact that reviewing was always a sideline. “This wasn’t writing,” Humphrey

remembers telling himself. “This was just studio practice put into words.”

David Humphrey, Blind Handshake (2009). Book Cover.

Describable

Beauty by David Humphrey One of the

inglorious reasons I became an artist was to avoid writing, which, thanks to my

parents and public school, I associated with odious authoritarian demands. I

found the language of painting, in spite of all its accumulated historical and

institutional status, happily able to speak outside those constraints. Of

course language and writing shade even mute acts of looking. The longer and

more developed my involvement with painting became, the more reading and

writing freed themselves from a stupid superego. Writing about art could be an

extension of making it. But there persists in me a lingering desire to make paintings

that resist description, that play with what has trouble being named. I was recently

asked to speak on a panel about beauty in contemporary art and found myself in

the analogous position of speaking about something that I would prefer resisted

description. Describing beauty is like the humorlessness of explaining a joke.

It kills the intensity and surprise intrinsic to the experience. I found,

however, that descriptions can have more importance than I originally thought.

The rhetorical demands of defining beauty often lead to ingenious

contradictions or sly paradoxes. It's amazing how adaptable the word is to

whatever adjective you put before it: radiant, narcotic, poisonous, tasteless,

scandalous; shameless, fortuitous, necessary, forgetful, or stupid beauty. I

think artists have the power to make those proliferating adjectives convincing

based on what Henry James called the viewer’s “conscious and cultivated

credulity.” A description can have the power to prospectively modify

experience. To describe or name a previously unacknowledged beauty can amplify

its possibility in the future for others; it can dilate the horizon of beauty

and hopefully of the imaginable. To assume that experience is shaped by the

evolution of our ingenious and unlikely metaphors is also helpful to artists;

it can enhance our motivation and cultivate enabling operational fictions, like

freedom and power. We are provided another reason to thicken the dark privacy

of feeling into art. Loving claims

are frequently made for beauty’s irreducibility, its untranslatability, its

radical incoherence. André Breton rhapsodized that “convulsive beauty will be

veiled erotic, fixed explosive, magical circumstantial or will not be.” Henry

James defined the beautiful less ardently as “the close, the curious, the

deep.” I think that to consider beauty as the history of its descriptions is to

infuse it with a dynamic plastic life; it is to understand beauty as something

that is reinvented over and over, that needs to be invented within each person

and group. Beauty’s problem

is usually the uses to which it is put. Conservatives use beauty as a club to

beat contemporary art with.

Its so-called indescribability and position at a hierarchical zenith makes

beauty an unassailable standard to which nothing ever measures up. This

indescribability, however, is underwritten by a rich tangle of ambiguities and

paradoxes. For critics more to the left, beauty is a word deemed wet with the

salesman's saliva. They see it used to flatter complacency and reinforce the

existing order of things. Beauty is here described as distracting people from

their alienated and exploited condition and encouraging a withdrawal from

engagement. This account ignores the disturbing potential of beauty. Even

familiar forms of beauty can remind us of the fallen existence we have come to

accept. When beauty stops us in our tracks, the aftershock triggers

reevaluations of everything we have labored to attain. Finding beauty where one

didn't expect it, as if it had been waiting to be discovered, is another common

description. Beauty’s sense of otherness demands, for some, that it be

understood as universal or transcendent; something more than subjective.

Periodic attempts are made to isolate a deep structural component of beauty;

articulated by representations of golden sections, Fibonacci series, and other

images of proportion, harmony and measure; a boiled-down beauty. Even in the most

unexpected encounters with the beautiful, however, there coexists some

component of déjà vu or strange familiarity. To call that experience universal

or transcendent performs a ritual act of devotion. It protects the preciousness

of one’s beauty experience in a shell of coherence. I think there are strong

arguments for beauty’s historical and cultural breadth based in our neural and

biologically evolved relation to the world, but arguments for artistic

practices built on that foundation often flatten the peculiar and specific

details that give artworks their life. The universalizing description also

overlooks the work’s character as a rhetorical object, subject to unanticipated

uses within the culture. It draws people toward clichés and reductive

stereotypes that are then rationalized as truths and archetypes. If I have any

use for the idea of beauty, it would be in its troubling aspect. I was describing

to a friend my mother’s occasional fits of oceanic rage during my childhood,

and she told me I should approach beauty from that angle. Like mothers, I

suppose, beauty can be both a promise and a threat. All roads eventually lead

back to family matters. Perhaps this path to beauty begins to slant toward the

sublime; to that earliest state of relatively blurred boundaries between one's

barely constituted self and the tenuously attentive environment. Attendant

experiences of misrecognition, identification, alienation, and aggressivity

during early ego development become components of the beauty experience. The

dissolving of identity, the discovery of unconscious material in the real, a

thralldom of the senses underwritten by anxiety, are a few of my favorite

things. If there is a useful rehabilitation of beauty in contemporary art, I

think it would be to understand it as an activity, a making and unmaking

according to associative or inventive processes. Beauty would reflect the

marvelous plasticity and adaptability of the brain. I'm tempted to

go against the artist in me that argues against words and throw a definition

into the black hole of beauty definitions; that beauty is psychedelic, a

derangement of recognition, a flash of insight or pulse of laughter out of a

tangle of sensation; analogic or magical thinking embedded in the ranging

iconography of desire. But any definition of beauty risks killing the thing it

loves. 1996

David Humphrey is a New York artist represented by Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York and Solomon

Projects, Atlanta. |

||||||||||||

|

Michel Batlle—The “new” has

been kicked in the head pretty

badly these past three decades with the re-emergences of neo-classicism,

abstraction, minimalism, and all the remixes of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s! How can there be new avant-gardes today, by

which I mean

true ruptures with the status quo? Ben—You’re

the one who says that the “new” has been kicked

in the head! It may be that all of these returns to the past result from

self-examination by the “new,” which refuses to be reduced to a gimmick; maybe

it is the new itself that is urgently reopening the question of the new. In any case, the new is essential; it is the

keystone of

art. What if the new is always around us, like the air we breathe? But this new would not be predictable; if it

were

predictable, it wouldn’t be new anymore! In the 1900s, when both painting and the notion

of beauty

were codified by representation, the “new” consisted in refusing

representation, and we got Duchamp. Today, now that painting and beauty are

codified by the “anything goes” attitude that resulted from post-Duchampian

gimmickry, perhaps the new consists of repeating the past, as you mentioned,

but with a different attitude. M.B.—Do artistic avant-gardes predict

social change? Ben—I would say

rather that they accompany change. And

since, in my view, the next change will consist in the elevation of minority

identities and cultures, I’m looking forward to seeing how the avant-gardes

will reflect this phenomenon as they explode in every possible culture. M.B.—What role should the artist take

on today, other than

that of a producer of primary material for the market and of images for

successive waves of fashion? Ben—You agree with

me that many artists are nothing more

than producers of gadgets or decorative objects whose sole purpose is to

satisfy the demands of the market. This is somewhat true, but wasn’t it always

the case? Giotto, Raphael, Michelangelo met the demands of the church as

market. Rembrandt did the same for the Dutch bourgeoisie by painting their

portraits, as did Stalinist artists who painted tractors to further the cause

of the Russian Revolution. Even the artist who tries to go against this grain

by producing political art is still making images for a specific clientele.

None of this is bothersome. It’s all

right with me if the artist is a pawn in the hands

of power, or produces images for his clientele, as long as he understands

clearly that this is what he’s doing. It may only be from that point that he

can become disturbing and creative. M.B.—Must the artist choose between making

art for an

elite—whether an intellectual elite or an economic one—and making art for the

general public, or is it possible to do both? And, for that matter, is there

still an intellectual elite? Ben—The artist always

works for recognition at the local,

national, and global levels. He would like nothing better than to have his

masterpiece distributed as a postcard! For this to happen, his work must be

personal and contain something new. The members of the elite are specialists.

There are people who specialize in furniture, leather, butchering, and sport;

they are specialists because they pay attention and know how these things work.

Non-specialists find things out from television or newspapers; the specialist

is right there, in the thick of it. If he is an important specialist who knows

the rules of the game and the powers that be, he can divine and predict who

will end up in the museum. In the final analysis, both the specialists and the

general public are different aspects of the same reality. This is the reality

that if an artist’s work is not personal, if he’s just playing around with

influences, even with some success, ultimately, it won’t work. Or, it will work

only in a limited sphere, such as that of official art or academic art. . . . M.B.—Could all of the irregularities

at the heart of the art

world that have come to light in multiple current examples of issues with

money, schemes, fraud, and sexual affairs produce a new kind of artist: the

artist as moralist, a kind of kamikaze artist who would want to infuse the art

world with rigor and a hard-core attitude? Ben—This kind of

artist has always existed. They are often embittered artists or

embittered demagogues. They see other people’s success as resulting only from

schemes, sexual liaisons, and deals. In fact, the best way to react against the

schemers is to produce new work and to believe in it. If one really has

something new, it will always stand out. After that, of course, the market

being what it is, the maneuvering begins and sometimes the new thing is

overvalued or undervalued. Since it’s a jungle, one cannot avoid this.

M.B.—The art made by young artists today seems

“made-to-order,” completely fabricated out of ingredients from the past. It all

seems like a cooking class! Clinical, “high-tech” arrangements, all kinds of

installations . . . . Does this constitute the new academicism? Ben—Creative people have a survival instinct that makes them

fear being passed over or falling behind. Some of them therefore may be

attracted to the “high tech” or the “clinical” which allows them to think

they’re up to date. This isn’t a problem as long as it allows them to be

themselves. Italian industry has succeeded in retaining its national

identity with “chiqueria,” which is a good thing. In any case, I don’t believe in universal art, the same art

for everyone. And since you haven’t asked me any questions about ethnicities

and minority cultures, I’m going to give you my position on this subject. I would say, first of all, that art is strongly attached to

political power, as I said in my response to the first question. The artist

frequently serves as illustrator to the political or ethnic power of which he

is the product. Pop Art depicted Anglo-Saxon consumerist society. When

Mexico had its revolution and acquired independence, Mexican art came into

being with Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros. When Catalonia was deprived of the autonomy and political

power it should rightfully have had, it became difficult for Catalan painting

to exist; Tàpies and Miro were taken for

Parisian painters. Artists need

their culture to be infused with political power in order for them to identify

with it. For a group to assert its difference before its artists, it

is necessary that it have the political power to which artists can come, react,

and receive the recognition they seek. They are free to make “high tech,”

“materialist,” expressionist or romantic art as soon as it is authentic and

comes from something the artist is ready to take on. This is valid for everyone in the world, for there are as

many visions of the world as there are languages and cultures. The Lapps have twenty different words for

“snow,” not a single word that designates the general concept. By contrast, in Burundi, there are only five

colors in their vocabulary.

Le

« nouveau » est-il toujours nouveau ? Une grande rétrospective de l’œuvre de Ben est actuellement

visible au Musée de Lyon, France. Cet entretien de Ben Vautier avec Michel Batlle qui a été réalisé en mai 1988 est toujours

d’actualité. Michel Batlle – Le nouveau a pris un sacré coup derrière la tête depuis ces trois dernières décennies avec les retours

néo-classiques, abstraits, minimal, et tous les remix des années 50, 60 et 70 ! Comment pourrait-il exister aujourd’hui de nouvelles avant-gardes c'est-à-dire,

de véritables ruptures ? Ben – C’est toi qui dis que le nouveau a pris un sacré coup ! Il se peut, justement,

que ces retours en arrière, proviennent du nouveau qui s’interroge sur lui-même, c’est le nouveau qui refuse d’être

réduit au rôle d’astuce, et, il se peut que ce soit le nouveau dans l’avant-garde qui remette en question le nouveau

à tout prix. En fait, cette histoire de nouveau est essentielle, c’est la clef de

voute de l’art. Et s’il y avait toujours du nouveau comme l’air qu’on respire ? Mais ce nouveau, parce que

à la recherche du nouveau, n’est pas prévisible, puisque, s’il était prévisible, il ne serait plus nouveau ! Dans

les années 1900, la peinture et la notion du beau étant figés dans le représentation, le nouveau a été de dire non à cette

représentation et nous avons eu Duchamp. De nos jours la peinture et le beau étant figés dans le « tout possible » des astuces

issues de Duchamp, le nouveau est peut-être ce retour en arrière dont tu parles mais avec, comme différence co-formelle qu’il

véhicule, une attitude ajoutée. M.B. – Les avant-gardes sont-elles prémonitoires des changements sociaux ? Ben - Je dirais plutôt qu’elles

les accompagnent et comme d’après moi le prochain changement sera une montée des identités et une réhabilitation des

cultures minoritaires, je m’attends à ce que les avant-gardes illustrent ce phénomène en s’éclatant dans le tout

possible des cultures. M.B. – Quel rôle devrait tenir l’artiste hormis celui d’être, aujourd’hui, de la matière

première pour un marché et un fournisseur d’images pour les modes successives ? Ben – Tu penses comme

moi qu’une grande quantité d’artistes ne sont plus que des producteurs de gadgets ou de produits de décoration

dont le seul but est de satisfaire un marché. C’est un peu vrai mais n’était-ce pas toujours le cas ? Giotto,

Raphaël, Michel Ange, satisfaisaient le marché de l’église, Rembrandt les bourgeois Hollandais en peignant leur portrait

et les artistes staliniens qui peignaient des tracteurs pour faire plaisir à la Révolution Russe. Même l’artiste qui

cherche à aller à contre-courant et qui fait du message social est aussi un producteur d’images pour une clientèle précise.

Tout cela n’est pas gênant. Je veux bien qu’il soit un pion entre les mains d’un pouvoir économique ou bien

l’illustrateur de sa clientèle, mais il faudrait qu’il le soit en toute lucidité. Et c’est peut-être là,

seulement, qu’il devient dérangeant et créatif. M.B. – De l’art pour une élite, celle de l’intellect et

celle de l’argent, mais aussi pour une reconnaissance plus large, celle du grand public ; faut-il choisir ou jouer sur

les deux tableaux ? Et puis, d’ailleurs, y a-t-il encore une élite intellectuelle ? Ben – L’artiste

travaille toujours pour la gloire, locale, nationale, mondiale. Il veut, en fin de compte, voir son chef-d’œuvre

diffusé en carte postale ! Pour cela il lui faut être personnel et apporter du nouveau. Ceux de l’élite, eux, ce sont

des spécialistes. Il y a des spécialistes en immobilier, dans le cuir, la boucherie, le sport, ils sont spécialistes parce

qu’ils s’en occupent et savent comment ça fonctionne. Les non-spécialistes regardent ça à la télévision ou dans

les journaux, le spécialiste, lui, est dans le coup. S’il est un grand spécialiste, connaissant les règles du jeu du

rapport de forces, il pourra deviner, prévoir qui finira dans le musée. Mais en fin de compte, que ce soit les spécialistes

ou le grand public, les deux sont tributaires de la réalité. Cette réalité est que l’artiste, s’il n’apporte

rien de personnel, a beau jouer d’influences et même réussir provisoirement, ça ne marchera pas ou alors, dans le cadre

de son énergie par exemple d’art pompier, d’art académique… M.B. – Toutes les indigestions du milieu de

l’art mises à jour par la multiplication d’exemples vivants comme les histoires d’argent, les combines,

les fausses côtes, les affaires de sexe au sein du milieu de l’art, ne risquent-elles pas , en réaction, de faire naître

un nouveau genre d’artiste : l’artiste moralisateur, sorte de kamikaze de l’art voulant insuffler une rigueur,

une attitude et un discours « pur et dur » ?

Ben – Ce genre d’artiste a toujours existé. Ce sont souvent des artistes aigris et parfois des démagogues aigris.

Ils ne voient dans le succès des autres que des combines, des affaires de cul et des surcotes. En fait, la meilleure

façon de réagir contre ces combinards est de produire une œuvre nouvelle et d’y croire. Si on a vraiment du nouveau,

il ressort toujours. Ensuite, bien sur, le marché étant ce qu’il est, la magouille s’installe autour et parfois

le nouveau est surévalué ou sous-évalué. De toutes façon, dans une jungle, on ne peut éviter cela. M.B. – L’art d’aujourd’hui

réalisé par des jeunes artistes apparaît comme un « produit fait sur mesure», complètement fabriqué avec les ingrédients du

passé. On a l’impression d’une course aux armements de cuisine ! De l’arrangement « high-tech » au « clean

clinique » et installations en tous genres… Est-ce là le nouvel académisme de l’art ? Ben – Les créateurs ont

un instinct de survie qui cherche à ne pas être dépassé, en retard. Alors certains pourraient être attirés par ce côté clean

» et « high-tech » qui leur donne l’impression qu’ils sont dans le coup. Cela n’est pas du tout gênant à

condition que cette impression leur permette d’être eux-mêmes. L’Italie a réussi

dans son industrie à être elle-même avec la « chiqueria », c’est positif. De toutes manières, je ne crois pas à un art

universel pour tous, le même art pour tous. Et puisque je vois que tu ne m’as pas posé du tout de questions sur les

ethnies, les cultures minoritaires, je vais te donner ma position sur ce sujet. Je dirais, tout d’abord, que l’art est fortement attaché au pouvoir

politique, ainsi que je le disais dans ma réponse à ta première question ; le rôle de l’artiste est souvent d’être

l’illustrateur du pouvoir politique et ethnique dont il est issu. Le Pop Art peint la société de consommation anglo-saxonne. Quand le Mexique

fait sa révolution et acquiert son indépendance, l’art mexicain avec Rivera, Orozco ou Siqueiros, existe. Tant que la

Catalogne n’avait pas une autonomie et un pouvoir politique qui lui étaient propres, la peinture catalane existait difficilement

; on prenait Tàpies et Miro pour des peintres parisiens. Les artistes ont besoin d’un pouvoir politique autour de leur

culture pour qu’ils s’y identifient. Pour qu’un peuple marque sa différence avant ses artistes, il faut que ce peuple ait

le pouvoir politique autour duquel ses artistes peuvent venir, réagir et recevoir la gloire qu’ils cherchent. Alors

libre à eux de faire de l’art « high-tech », « matiériste », expressionniste ou romantique du moment qu’il est

authentique et vient d’un quelque part que l’artiste est prêt à assumer. Cela est valable pour tous les peuples du monde

car il y a autant de visions du monde qu’il y a de langues et de cultures. Les Lapons ont vingt mots pour dire le mot « neige » et pas un seul pour dire neige en général. Par contre

dans le Burundi ils n’ont dans leur vocabulaire que cinq couleurs.

Michel Batlle is an artist and gallerist of Catalan origin based outside

of Toulouse, France. He

is the founder of several journals, including Articide Circuit, established in 1993. http://michelbatlle.free.fr/cv.htm

The

exhibition Strip-tease intégral de Ben is at the Musée d'art contemporain de Lyon, France, from 3 March - 11 July 2010.

Arshile Gorky

at Tate Modern by Anna Leung Arshile Gorky was a romantic figure, a double outsider whose life was

dogged by misfortune. Despite the facts that one drawing from his series Nighttime,

Enigma and Nostalgia

and one painting from the series Garden in Sochi were acquired

by the Museum of Modern Art in

New York, and that two one-man shows were held at the Julien Levy Gallery, one

in 1945 and the second in 1947, on the whole Gorky met with a cool reception at

a time when the young generation of Abstract Expressionists were preparing to

wrest artistic hegemony from Paris. Even when Clement Greenberg, the eminence

grise behind the rise of the New York School who was at that time pushing

Pollock into the glaring flood lights of celebrity, admitted that Gorky had

made the grade and was the equal of any of his generation, he clawed back this

compliment by accusing him of hedonism, a typically French failing that smacked

of aestheticism, and was therefore inherently un-American. Little wonder then

that Gorky from the first concealed his Armenian identity and took on the

fiction of being the famous Russian writer Maxim Gorky’s nephew, even though he

could not speak Russian. He saw himself not as a tragic figure but “as a man of

fate.” This sense of fatality can be traced to his mother. It was she who called him “the black one, the unlucky one who will come to a no-good end.” She was both right and very wrong. The double portraits of the young Gorky and his mother, transcribed from a photo originally sent to his father in 1912 to remind him of their existence, occupy the centre of the exhibition – a room devoted to portraiture which while biographical also functions as a homage to Cezanne and to Ingres. The two figures look down at us with eyes of deep loss and longing, his mother belonging to the past and the old country, the young Gorky belonging to the land of the future. Together with other portraits of family and friends, this space at the heart of the exhibition reminds us of the overwhelming sense of loss which is the experience of the émigré, a loss that informed Gorky’s life and continued to haunt his work. His exotic and maverick genius came to the fore after a childhood of persecution and near starvation and once in America was honed by years of apprenticeship to European modernism. Arshile Gorky was born between 1902 and 1905 in Turkish governed

Armenia. His real name was Vosdanig Adoian and his family on his mother’s side

came from a noble line of priests, some of whom were revered as martyrs.

Throughout the centuries Armenians had persistently suffered persecution at the

hands of succeeding waves of Arabs, Mongols and Tartars. During all this time

it was the Armenian apostolic church that represented the Armenian people and

constituted a force preserving their cultural identity. Ironically it was the

Ottoman Turks who brought a temporary reprieve to this persecution and a

modicum of peace and tolerance to the Armenian people. But by the nineteenth

century, with Turkey becoming “the sick man of Europe,” this tolerance began to

wane, at the same time that Armenians, coming into contact with revolutionary

ideas from the west, were beginning to demand an independent state. Massacre

followed on massacre and many young men choose to emigrate. One of them was

Gorky’s father who left for America following in the footsteps of two of his

uncles who had emigrated in 1896. He virtually abandoned his family, leaving

them to face a sustained and systematic policy of brutality and starvation

which was followed up in 1915 by “a death march” when the Armenians were forced

to flee on foot to Russian Armenia which was then still part of the Russian

empire. In 1918-19 there was a famine and the refugees starved. Twenty percent

of the Armenian refugees died of cholera, typhus or dysentery. It was the news

of this human catastrophe that gave rise in the States to the common place

phrase “starving Armenians” which made Gorky all the more determined to hide an

identity that caused him so much shame and re-awakened terrible haunting

memories. He was not willing to take on the stigma of refugee status. Whether

the onslaught against the Armenian population constitutes genocide remains a

hotly contested subject of debate in the United Nations assembly. It was during

this period that Gorky’s mother died in his arms. She had starved to death. Two

months later Gorky and his sister embarked on their journey to America arriving

on Ellis Island in February 1920 and were met by family who took them to their

home in Watertown, Massachusetts. By high school Gorky had already decided he

wanted to be an artist. He attended the Technical High School in Providence and

took up various lines of employment before moving to Boston in 1922 to enrol at

Boston’s New School of Design, and it was probably at this time that he changed

his name and took on his new persona. Two years later he had so impressed his

tutors that he was invited to teach part time in the life drawing class. In

1924 he moved to New York, followed art courses at the New School of Design but

was chiefly self taught, studying and scrutinising the old masters, traditional

and modern, in the many New York museums. Apprenticeship to

European Modernism Gorky never set much store by “the modern imperative of originality” but

believed in learning from his predecessors, catching up on the great European

tradition that had culminated in Picasso. By the mid twenties Gorky had

discovered “Papa Cezanne” and was able to develop a style almost

undistinguishable from this founding master. From Cezanne he took nature as his

starting point in his journey towards abstraction. He then went on to emulate

Picasso, exploring his strategies, both figurative and abstract, including Amazonian

nudes and the shallow spaces of Cubism, and by the thirties he had succeeded in

resolving his subject matter into interlocking abstract shapes. Gorky was

ambitious. His aim was to assimilate what he could from art history in order to

add to it; a traditional project for artists till the advent of the modern

period which demanded total originality. His series of drawings Nighttime,

Enigma and Nostalgia (1931-33)

already seemed to attest to his closeness to Surrealism and the idea of psychic

automatism whereby the artist allows his hand to move over the paper or canvas

without any purposeful or conscious control. But this was far from the case,

since, as in all his work, Gorky experimented in advance with all manner of

permutations and continued with the age old practice of squaring up his sketches

before transferring them to a canvas. Inspired principally by Miro and Masson

he created forms that meander and create a maze of lines. Using elaborate

crosshatchings and veils of coloured ink these shapes were transmuted into ever

changing relationships that were already sexually suggestive. In Nighttime,

Enigma and Nostalgia

Gorky integrated cubism and the mystery of de Chirico (the bust and skeletal

fish) with Jean Arp’s biomorphism. All this in drawings that demonstrated a

sureness of draftsmanship based on Ingres’ delicacy of line and were

compartmentalised in the manner of Uccello’s Miracle of the Host,

a reproduction of which he had on

his studio wall. In 1930 Gorky had moved to a larger studio in Union Square, which was the liveliest place to be in New York at the time. His fictitious curriculum vitae now included three months of study under Kandinsky. Alfred Barr the head of Moma came to his studio and, although somewhat dismissive of his obviously derivative style and his dependence on the School of Paris, he invited Gorky to participate in an exhibition of artists under 35 years of age. Three still-lifes were chosen; this led to other group shows, and gradually Gorky began to gain a reputation. His momentum was disrupted by the Depression which, however, had its up as well as obvious down sides. The Depression brought artists together in their struggle to survive and changed the artists’ relationship with society. But even being accepted as part of the Federal Art Project did little to lessen Gorky’s sense of being an outsider and this was partly due to his own inherent anti-Americanism, his conviction that European art was far superior to American home-grown art making. His close friend de Kooning, with whom he had shared a studio, recalls that Gorky thought that America had no real art, that it was basically regional or vulgar, and was that he was far from discreet in promulgating such views. However he welcomed the opportunity, when it came, to take up a New Deal PWAP (Public Works Art Project) offer to produce a set of murals for Newark Airport

Public Works Art

Project Very little of Gorky’s work on the murals for Newark Airport has

survived. The analytic composition was based on the mechanical shapes of

airplanes and derived stylistically from Picasso, Léger and Ozenfant. Gorky

dissected the mechanics of the airplane into their constituent parts. It is

significant that this strategy already represented a conjoining of a Cubist

aesthetic with the beginnings of a Surrealist agenda in that he took a

well-known object out of its normal context in order to defamiliarise it – in

Gorky’s own words “making from the common - the uncommon.” While this project, with its machine age

aesthetic, was not that characteristic of Gorky’s oeuvre, he nevertheless

continued to explore the potential of this type of hard edged, flat coloured

painting in a large canvas Organization (1935) that was based on two of Picasso’s

paintings The Studio (1927-8) and Painter and his Model (1919). Basically a still-life contained

within a horizontal and vertical armature of strong black lines it is assembled

against a white background which Gorky reworked with many layers of paint. He

was famed, despite his poverty, for his profligacy with expensive oil paints. Organization gave rise to a series of

still-lifes in which the biomorphism characteristic of Nighttime, Enigma and

Nostalgia

reappeared presaging a return to the more poeticised organically charged

paintings of his Khorkom theme and his series of Garden

in Sochi, both of which were based on his childhood in

Khorkom the village of his birth. It is no secret that Gorky was inventive about a

childhood that must have been distressing to say the least and yet was often

remembered as beatific. He probably invented much of this happy childhood since

in reality conditions were primitive and poverty, even in the good times, all

too habitual. But in conversation he remembered the devotion to the land, the

gathering of the apricots in his father’s orchard and the tilling of the fields

with a plough fashioned out of a tree branch. His fondness for these rituals

came out in his art together with a magic that invested his landscapes with a

spirit of animism that can be traced back to his love of Coptic and traditional

Armenian folk arts. A new period began after Organization; his style became far looser,

his

use of paint more impulsive and his modulated colours were earthy and warm.

These paintings conveyed vestiges of figuration but the shapes were

indecipherable or ambiguous, often suggestive of birds, female figures and

something that could be a butter churn or boot that would reappear in later

works. Basically it was as if shapes that were still contained in Organization’s cloisonnist structure had been

released into a more spatial area of play but one in which no one identifiable

image could take centre stage. These paintings, and the series of Sochi that

followed, seemed to have a

hidden narrative that linked in with Gorky’s childhood but also coincided with

a period of much happiness when he began living with Agnes Magruder who was to

become his wife and mother of his two daughters. From Hans Hoffman, the émigré

artist who did most to advance the cause of abstraction in the States, Gorky

had learnt about negative and positive space and the need to keep the picture

plane flat while at the same time creating a sense of balance by setting up a

state of tension between shapes. The problem facing the American artist was

that of bringing abstract form and meaning together. For artists such as Rothko

and Pollock the advent of Surrealism contributed to the part resolution of this

problem. Gorky at this particular time was still close to his European masters,

only Mirò had replaced Picasso, with all the lyricism that such a move would

entail, while in addition providing a new theoretic outlook and a new vision. Surrealism Many of the best known European Surrealists fled to the States in 1939

when war was declared in Europe, and though Gorky was already conversant and

sympathetic with surrealist theories, the presence in New York of Breton, Mirò,

and Matta had a further liberating effect on his vision. This sense of release

was especially noticeable in a series of drawings from early in the 1940s made

on site during a stay with the artist Saul Schary in Connecticut in which the

whole landscape was activated with indecipherable cryptograms suggestive of

fecundity and growth. It was here too that he painted Waterfall (1942)

which technically

represented a totally new approach with its washes of turpentine diluted oil

paint and a far freer handling of line no longer confined by colour. Waterfall was

abstract and yet succeeded in

conveying the sense of water falling over rocks. Of greater significance,

however, was the fact that, as in surrealist paintings, landscape had become

mind- or inner-scape. It is important to underline that though Gorky was very

close to Breton and Matta he never really adopted surrealist practices; he felt

greater affinity with Kandinsky’s idea that beauty had its origins in an

“internal necessity that springs from the soul.” Moreover, control was

important to Gorky. He was a great perfectionist and therefore had no real

sympathy with the idea of psychic automatism, though he understood full well

the way the unexpected and accidental could form bridges to the unconscious

mind and reveal another reality, an inner world that speaks of a primordial

unity between man and the universe. In common with many artists who were to

make up the New York School of Abstract Expressionism, rather than finding a

compatibility with Freud Gorky found compatibility with Jung, rather than

Freud, who spoke for an art practice that stressed the collective unconscious

and was therefore beyond psychoanalytic interpretation. However,

in many cases the presence of the Surrealists, especially in New

York, was irksome and gave rise to real resentment among local artists

since the Surrealists were

fêted as the celebrities of the art world and given the exhibition space the

younger artists thought should have been theirs’ by right. Gorky’s case was

different. It was through Breton’s support that he was able to sign a contract

with Julien Levy, the dealer who had done the most to promote Surrealism in

America. Breton

and Duchamp persuaded Julien Levy that Gorky had come into his own and that

his paintings were

no longer derivative. He was no longer a Picasso copyist. With a regular

stipend, Gorky finally achieved the financial stability he needed at a time

when he had become responsible for a growing family; his eldest daughter, Maro,

was born in 1943. Andre Breton also helped choose titles for the paintings that

were to go on display at Gorky’s first one-man exhibition, which opened at

Julien Levy’s Gallery on March 6, 1945. Breton also wrote the foreword to the

catalogue. The Eye-Spring: Arshile Gorky emphasised the analogical character

of Gorky’s

vision that enabled the artist to turn his forms into hybrids that brought

together the actually seen and the remembered. This closeness to the

Surrealists was not totally advantageous to Gorky. Surrealism was anathema to

Clement Greenberg, who accused Gorky of lacking “independence and masculinity

of character,” an especially cruel and humiliating taunt to someone coming from

Gorky’s background. Only two paintings were sold and no new patrons found for

Gorky. From this point onwards Gorky was to suffer a catalogue of misfortunes.

He had become “the unlucky one” just at the point when elements in his

paintings were beginning to coalesce and he was at last receiving critical

acclaim.

“The Unlucky

One” In 1946 Gorky was preparing for his second one-man show at Julien Levy’s

Gallery when a fire broke out in his studio in Connecticut and all the canvases

he had been working on were destroyed. Gorky was known to have a passion for

fire, always building huge bonfires or, as in this case, stacking the

pot-bellied wood burning stove too high. But he was also keenly aware that his

family was said to live under a curse. His grandmother had set the local church

on fire in revolt against God who had allowed her son to be tortured by the

Turks. So when his studio was burning, he acted as if under that curse, not

informing the fire brigade but trying to staunch the flames himself. This was

to be the beginning of a litany of misfortunes that befell him; in 1947 he

underwent extensive surgery for rectal cancer and in the same year his father

died, but having kept his existence hidden even from his wife, he was unable to

really mourn him and give vent to his grief. The following summer of ‘48 he

broke his neck in a car accident and, while this was healing, suffered

paralysis of his right arm and was convinced that he would never paint again.

Finally his wife, ground down by his depression and worried on account of the

children and his increasing violence, moved back to her parents’ house. Three

weeks later, in July of 1948, Gorky hanged himself, leaving a note for them

that said “Goodbye, my loveds.” After the fire, Gorky at first

had characteristically met adversity with

renewed vigour, throwing himself into his work and recreating from memory the

canvases that had been lost in the conflagration. There were also new

paintings, such as Charred Beloved and The

Betrothal. His canvases had become much more

complex, his colour more muted and more chromatic, his textures denser; it was

as if he had found his own language. The Plough and the Song (1947) is resonant with feeling,

its subject matter probably a celebration of fertility though identification of

the concatenation of shapes is virtually impossible. As in cubist paintings,

forms and their meanings are multivalent. The Limit (1947), with its almost

monochromatic expanse of gray, suggests a terrible emptiness and seems weighed

down by a loneliness that reminds us of those orphaned and plaintive eyes of

the young Vosdanig Adoian in the photo of himself and his mother. It is as if

this sense of overwhelming loss never really left him despite his efforts to

integrate himself in American society. Viewing

the paintings at

the second Julien Levy Gallery exhibition, Greenberg conceded that Gorky had

come into his own. But he significantly withheld the real accolade by insisting

that Pollock was still the greater of the two. Predictably, Gorky no longer

needed Greenberg’s approbation after his death. His fame spread and his prices

at art auctions escalated. Historically, Gorky is now seen as a transitional

figure marrying abstraction and surrealism, cubism and abstract expressionism.

But Gorky was no Surrealist despite his acute understanding of the relationship

between poetry, memories of childhood, sex and pain. He did not share their

scorn for fine art and for art history but was moved by a deep reverence for

the craft and history of painting. There was no room in his practice for

anti-art or non-art. Similarly Gorky was not a proto-Abstract Expressionist.

Unlike artists such as Barnett Newman, Rothko, and Pollock he had no wish to

deliver himself from the artistic hegemony of the European tradition. By

identifying with the Europeans, Gorky never became an American artist, despite

his naturalisation, as his friend de Kooning succeeded in doing. Like so many

romantic artists, he had to wait for death to bring him. © 2010, Anna Leung

Anna Leung

is a London-based

artist and educator

now semi-retired from

teaching at Birkbeck

College but

taking occasional

informal

groups to current

art exhibitions. Arshile Gorky: A Retrospective was at theTate Modern, London, from 10 February - 3 May 2010. It is at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles from 6 June - 20 September 2010.

|

||||||||||||