|

|

|

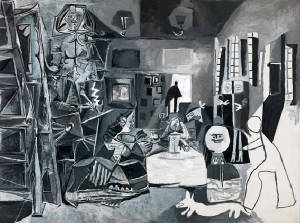

| Pablo Picasso, Las Meninas (after Velázquez), 1957. Courtesy: Museu Picasso, Barcelona. |

Introduction

by Deanna Sirlin

Editor-in-Chief

This month brings us an evocative dialogue between Mark Scala and Philip Auslander that explores the physicality of painting

in relation to the body in performance. Figurative painting is lushly discussed here, including artists such as Picasso and

Bacon. Anna Leung brings us a separate discussion of Picasso, who has been the subject of many recent exhibitions in Paris

as well as the one at the National Gallery in London that she challenges here. I saw both the Paris and the London exhibitions

and preferred the one in London, which did not include the masterworks except on small cards in the gallery. Next to the

“original,” the Picasso is a friendly annoyance. Without it, we can enjoy his pictorial language fully and directly

the way I believe he meant it to be perceived. Anna offers her reading of this side-by-side examination of Picasso and the

past.

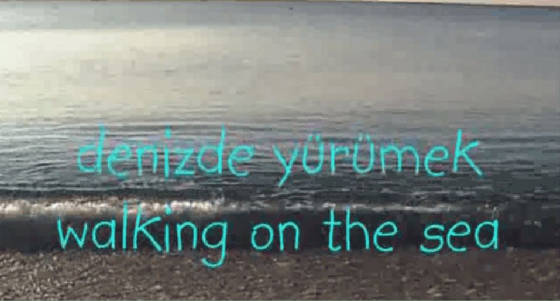

We also have a short video by the Turkish artist Imren Tüzün. I am delighted to present this artist through this refreshing

and thoughtful work. The Art Section will be presenting many artists’ projects in the coming year. and I am delighted

for it to be a vehicle for such presentations.

This is our second anniversary issue. I am happy, and thankful to all who have supported this journal in the last two years.

I will not say it has not been a challenge, but as we all know, few things worth working on are simple.

all my best,

Deanna

www.deannasirlin.com

|

| Jenny Saville, Hyphen, 1999. Courtesy: Gagosian Gallery. |

Paint

and Performance:

Mark Scala, in Dialogue with Philip Auslander

During a recent visit to Nashville, Tennessee, I visited the Frist Center

for the Visual Arts. The Frist's Chief Curator Mark Scala very kindly took me on a personal tour of the exhibition Paint

Made Flesh (January 23 to May 10, 2009, then traveling to The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC, and the Memorial Art

Gallery, University of Rochester, NY) during which he told me he could imagine a different version of the exhibition that

would extend the exhibition's focus on representations of corporeality in post-war painting to other forms, such as performance.

This began a conversation between us around questions concerning paint and performance as media and aesthetic forms that we

continued by e-mail, for The Art Section. –PA

Mark Scala:

As we discussed, thirty years ago there seemed to be a tremendous divide between painting and performance art. While there

was a recognition of the precedent of Pollock as a "performer" of action paintings, particularly as this influenced Happenings,

I would say that the prevailing view of leading critics and the artists they supported in the 60s and 70s was that painting's

performative dimension was irrelevant, clearly not the end in itself, the thing that is meant for audience consumption. Painting's

slowness and its mediation/filtration of reality, its being anchored to the past, its arm-length distance from the body of

the maker, the taint of its commodity status all outweighed any sense of its being as legitimate a way to directly express

such subjects as the abject body as a crucible of outer conflict as, say, performance work by Carolee Schneeman or Hannah

Wilke.

Now, of course, it is easy to see that all mediums intrinsically involve construction (material and/or conceptual),

whether conceived in the privacy of the studio, or as in performance, the privacy of the mind; and that there is power embedded

in any significant visual object (to toy with the word a bit, one might consider the visual/auditory experience of a performance,

like any image-generating force, as the "object" of one's attention, which after viewing resides in the mind's eye with all

those other memorable objects one has seen).

A video or photographic documentation of a performance is also a physical

object; its relationship to the artist's action is indexical, just as the brushstroke is an index of the artists hand and

mind working in concert with tangible material. Whether viewing a tape of Schneeman's Meat Joy or de Kooning's painting

Woman Accobonac, one inevitably is drawn back to the artist, the maker, and the action of making; looking at Meat

Joy, my mind has me rolling nakedly around on the floor, smearing bloody chickens (and what a lovely image that is!);

looking at the de Kooning, I rebuild it with my hands, metaphorically scooping the "human paste" (as Jenny Saville calls paint)

off of the model, with all the implicit sexuality and violence that contains, and then rebuilding it with emotional pitch

instead of anatomical structure.

This idea of the stroke of the brush as a conduit of the artist's flesh (by this I don't mean physical flesh, but the desires

and forces that we refer to as "things of the flesh") is carried through in other paintings in the "Paint Made Flesh" exhibition;

it is shown in the CoBrA painting of Karel Appel, who claims to be striking out, attacking the canvas, in atavistic fury at

the inhumanity of the Holocaust, concentration camps, Hiroshima, etc; and again in the ideogrammatic work of A. R. Penck,

which evokes a precognitive state, proposing an alternative to rational language (visual, written, or spoken)as an instrument

of ideology, with the idea that the arm that applies the paint is the action-maker of the body, which has its own autonomic

imperatives and psychic memories that defy conceptual articulation.

Philip Auslander:

I agree with your suggestion that performance be thought of as a medium commensurable with other

media. It seems to be the case that the critical orthodoxy you cite is the product of a very brief moment, probably between

about 1968 and 1972 or so, when the anti-object rhetoric was at its height. Just before that, Michael Kirby had taken a rather

different approach in his book on Happenings, published in 1965. Kirby defines the Happening as a work by a single artist

(such as Robert Whitman or Claes Oldenburg) and the bodies used in them essentially as raw materials, akin to paint, whose

presence and deployment are entirely determined by the artist and constitute the realization of his artistic concept (I say

"his" because all of the artists Kirby discusses are male). After 1972, a number of the artists in the vanguard of body art

turned (or, in some cases, returned) to making objects. Vito Acconci is a good example, as he progressively disappeared from

his work. He began with performances and participatory works in which he put himself and his body on the line, but then moved

to installations featuring his recorded voice but not his physical presence, and finally to sculptural pieces and installations

that do not reflect his corporeality in any direct way. Beyond that, of course, some performance artists ultimately engaged

in a wholesale embrace of the object and of commodity culture, particularly Laurie Anderson, whose work appeared in galleries,

movies, mainstream performance venues, on records and in books published by a large media conglomerate, and so on.

Once we start talking about performance documentation, a hot topic these days, we risk getting lost in a thicket! For example,

many would disagree with your comparison of the performance document to the painting (without necessarily disagreeing with

you that they both point indexically back to the action of the artist in making the thing). Strictly speaking, it could be

argued, the live performance is analogous to the painting, in that it is the product of the artist's action, and the performance

document is analogous to a reproduction of the painting.

MS:

I would not say that painting and the documentation of a performance are each the primary expressions of an

artist; only that they are both indexes of mental decisions and bodily actions, one recorded in paint, which is the

painter’s primary medium, the other documented in film, which, while not the primary medium shares enough of the properties

of the performance, and brings its own aesthetic properties, so that it might be comparable to a painting in being

a work of primary authorship.

PA:

The usual assumption is that performance documentation gives us, at best, an impoverished experience of the original performance.

But the more I think about it, the less credible I find this privileging of the live event. You mention that images from documented

performances stick in your mind the same way a painting can. I believe this to be true, and it suggests that one can have

an experience of the performance itself as an aesthetic object from its documentation. We have seen that often reproduced

images from performance documentation, such as the one particularly famous one from Schneeman's Interior Scroll, become

iconic images that, over time, come to represent that performance not just in personal memory but for purposes of scholarship

and analysis. The question of just what the image actually indexes becomes less and less important even to the point, I argue,

that it may not matter whether or not the performance ever actually took place! For example, Yves Klein's famous Leap Into

the Void, a doctored photograph that shows him flying out of a window into the street below, from which the safety net

that was present has been removed, is just as iconic a piece of "performance" documentation as the image of Interior Scroll

and provides the same visceral identification you describe in your response to images even though what we see in the photograph

never took place in the way we see it.

MS:

I think you are right. Several questions arise: when is documentation just archival, and when does something new, different,

interpretive, engaging, or expressive happen in documenting a performance that makes the responding work a distinct artistic

expression? And for artists who work in performance and video, is there any reason to draw a line between the two, even when

the second captures the first? Does it matter if the performance is being done “for” the camera, or for the live

audience? I would say not. Any distinction does not necessarily alter the aesthetic validity of the work—if the experience

of each is different, as I have said, it’s because every medium has its gifts.

PA:

Upon reflection, I don't think documentation is ever just archival: the document always becomes a work (of some kind) in itself,

even when the intention is to produce a more or less transparent archive of an event. I tend to think of these matters on

the analogy of musical recordings. A bootleg recording of a concert is intended as a pure document, as opposed to commercially

produced live recordings, which are frequently cleaned up and altered. Certainly, the bootleg does not participate in the

aesthetics of sound recording in the same way as the commercial recording and does not avail itself of the expressive possibilities

of the medium. But it is nevertheless governed by a "bootleg aesthetic" that is tied indexically to both the action of the

bootlegger (the person who made the recording) as much as those of the musicians, and participates in powerful ideologies

of authenticity. I think of the photos of Chris Burden's Shoot, for instance, in much the same way. They aren't much

as photos, but their authority and authenticity as objects is produced in part by that very fact, like a bootleg recording

of a rock concert that doesn't sound like a professional recording but is perceived as more authentic for that reason. In

any case, except for the miniscule number of people who were actually in the gallery, the photos are the event.

The analogy I mentioned between the performance document and the reproduction of a painting breaks down because, in principle,

the original painting remains available to be experienced. If the reproduction is indexical, we can actually have a direct

perception of the thing it indexes. The performance document, by contrast, is akin to a reproduction of a painting that no

longer exists--its indexical function has been sundered because we cannot access the thing it ostensibly indexes. Therefore,

the only experience we can have of the "performance" is the experience of the document (and this is true whether the document

records an event like Meat Joy or one like Leap into the Void). All of this is a roundabout way of saying that

I think the parallels between performances, performance documents, and paintings and other art objects go even deeper than

you suggest once one starts to think about both as processes of image-making.

|

| Willem de Kooning, Woman Accabonac, 1966. Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. |

MS:

I suppose it could go without saying that a photo-based record of an actual, tangible experience fulfills most

viewers' habits of conflating the two (it’s why documentary movies can trigger such empathy), or at least thinking the

two might yield a roughly equivalent experience. Whereas a photograph of a painting is generally understood to be a shade

of a constructed fiction, in which the experiential triggers—textures, transparencies, malleability in response to changing

light, etc.--that distinguish it from other types of image are not always so evident. We have only the image. So with regard

to this exhibition, a point that I try to make is that each medium has its gifts and limits, some that can be captured via

documentation, some that cannot; the thing that distinguishes painting is its metaphorical capacity to tactilely, viscerally,

and visually suggest multiple states of being all at once. One need only look at Francis Bacon to see how flesh, blood, sinew,

semen, bones, eyes, asses, photographs, rooms, beds, lust, anger, and fear are all mashed therein; this is to me a very close

approximation of the unsortable nature of the human mess.

PA:

The question I would like to raise here is: If painting is able, as you say, to convey multiple states at once metaphorically,

what about performance? Does the presence of "real, live" bodies in performance limit its ability to function metaphorically?

Is a single body capable of representing multiple states, or is it limited to whatever its present state may be?

MS:

I cannot think of a resonant expressive medium—painting, film, literature, theater—that cannot engage or evoke

multiple conditions simultaneously. Clearly, bodies in a performative relation to the viewer can function metaphorically and

sometimes in complex, contradictory ways—through language, posture, bodily adornment, interaction with others, facial

expressions, costume, stagecraft, etc. And yes, the single body, especially through time, can represent multiple states.

What I am saying is that the visual experiences that paintings proffer can have a different quality of tactile associations—not

just skin on skin or eyes on skin (does a performing body enable one to feel that he or she is looking within, through

the skin of the performer?). Instead, a particular kind of painting, say by Bacon, suggests skin on flesh, with the eyes as

the proxy for the fingers feeling the slippery, rubbery, sinewy, meaty interior. The historical vocabulary of painting has

the capacity to evoke two kinds of internality—this anatomical/visceral kind, and the emotional (evoked by color, gesture,

texture)--and two kinds of externality: the appearance of the body and its social role. It does so in a fixed fashion, which

might encourage us to think about paintings as a counterpart to physically present bodies, which we also imagine to be fixed

(as opposed to a faster, or more temporal, expression like performance).

PA:

I find this very interesting, though I may have some difficulty in formulating my thoughts clearly. What strikes me may be

a paradox: that performance, whose material is living bodies, cannot give us access to the interiority of bodies and subjects

as effectively as painting. (I think performance can, and does, foreground the two kinds of externality you mention.) Those

invested in performance (of all kinds—not just performance art) want to believe that we can access those levels of experience

by witnessing performance, but the reality is we can't. (There is a distinction to be made here between the experience of

the audience and that of the performer—I don't doubt that performers can use the act of performing to explore their

own interiority, both physical and psychic. But I'm not sure how much of that actually translates to the audience, even in

the face of the audience's belief that it does.) The presence of performers as living, human beings (whether live or in recordings)

before us heightens both the desire to get inside their heads and skin, and the belief that performance somehow permits us

to do so. But the reality is that although performance encourages the illusion of exposure, it inevitably frustrates the desire

for it. I don't mean this as a negative comment: this dynamic is one of the things that makes performance compelling and keeps

us coming back for more. But it also means, as you point out, that Bacon can get us inside the body and the subject

in ways that performance seems to promise but never accomplishes.

MS:

It would be interesting to re-make the exhibition someday, adding counterpoints in which flesh is "not paint"--one thinks

not just of photographic, performance, and video/film work, but also works by such artists as Kara Walker, for whom the depicted

void where flesh should be is a contemplation of the muting of identity (especially as defined by the tangible body) pitting

the power of one's physical and sexual being against the social structures (relating to race and gender in particular) that

have been contrived to deny such power.

But Paint Made Flesh hones in on the subject of paint's palpability

as an extension of the things of the artists' flesh, and through empathy, our flesh. Partly because it functions within a

recognizable historical code that is the inheritance of Titian, Rembrandt, Goya, and Soutine, and partly because of its mutable

material characteristics, the medium of paint provides a ready-made language for the exploration of the discourse between

presence and absence, desire and repression, memory and death, and artistic process and visual consumption.

Mark Scala is the Chief Curator of the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville, TN.

www.fristcenter.org

Philip Auslander is the Editor of The Art Section.

www.philipauslander.com

|

|

|

|

|

Denizde Yürümek/Walking

on the Sea

A Video

by Imren Tüzün

To watch Walking on the Sea, click on

the image above.

Windows users may need to download Quicktime for Windows here.

Throughout history, the Mediterranean region has been the stage for a number of important migrations,

the product of which is the “Mediterranean Civilization”. And the same goes for our country located in the Mediterranean.

The ancient civilisations it has hosted, the subsequent population exchanges, and the attraction it holds for people of today

have kept the Mediterranean pulse beating and ensured its place on the agenda.

The slippers trying to ride the waves signify those who migrate to places away from here and those who migrate here from other

places. The intention is to draw attention to the state of being of the Mediterranean.

Imren Tüzün is an artist who lives and works in Antalya, Turkey. Walking on the Sea, was selected for the 5th International

Short Film Festival in Detmold, Germany, June 4-7 2009.

www.imrentuzun.com

|

| Pablo Picasso, Seated Woman, 1920. Courtesy: Musée Picasso, Paris. |

Picasso: Challenging the Past

At the National Gallery, London

by Anna Leung

This exhibition revolves around the persistence of the Western canon in the whole of Picasso’s oeuvre and the importance

of the old and modern masters to his art practice. It comes close to intimating that without the infrastructure provided by

these masters Picasso would not have had a matrix out of which to extract his own radicalising vision. This goes some way

toward explaining why his engagement with abstraction remained liminal; his own story, and that of his predecessors, was too

important. Such an approach substantially modifies the history of modern art that takes Cubism as its main point of inception.

For as long as this was the prevailing view, Picasso’s radical innovations tended to be allied to his appropriation

of Iberian sculpture and of African masks and the conceptual somersault to which this reorientation gave rise. The sense of

drama Picasso created through his deconstruction of figures and objects within a Cubist framework of fractured and angled

planes was interpreted as an avant gardist assault on tradition. Picasso, Challenging the Past attempts to realign

Picasso with the great artists of the past whom he both revered and rivalled, to reintegrate him within the grand tradition.

Whether it is successful in this aim is one matter and whether Picasso is successful is yet another.

Picasso, Challenging the Past suggests, therefore, a more conservative, though not necessarily a regressive, orientation

and has as its main aim to illuminate the fact that right from the start, Picasso was engrossed in a dialogue with the Old

Masters. It was previously assumed that his "old master period" was confined to his late period from the late 1950s, when

Jacqueline Roque, his second wife, jealously guarded his privacy and he, by this time himself an old modern master, was leading

an increasingly solitary life at Mougins. In the absence of the stimulus of museums and galleries, Picasso sought the company

of the great through reproductions and slides, which he projected on the wall whilst actively sparring with them. Paris was

by then no longer the hub of the contemporary art world, having been overtaken by New York, and abstraction was in its ascendency

with the emergence of Abstract Expressionism in the States. This is the period dominated by his studies of iconic masterpieces.

Whether this was motivated by a need to appropriate them or outrival them, whether his need was to honour them or honour himself

remains an open question.

Not all of Picasso's incursions into the territory of the great masters met with unqualified success. Indeed, his variations

on Delacroix, Velazquez, and Manet have been cited as evidence not of his genius but of a distressing lack of it; worse still,

they have been taken as a demonstrations of his inability to outrival them that exposes a deep seated narcissistic rage and

envy. It has sometimes been argued that this rage and jealousy, plus evidence of a sadistic streak, explains Picasso's disfiguring

manipulation of the female form resulting in the creation of rapacious monsters of ugliness that contrast with paintings of

"la femme fleur" which represent his happier, Arcadian moments with a new love object. It may be that Picasso did not consider

this subject matter ugly in the conventional sense or, if he did, he may have perceived it as an ugliness that was not necessarily

autobiographical but an index of the ugliness in the world around him, just as the still-lifes he painted during the occupation

of Paris by the Nazis refer not to his own curfewed existence but to the larger subjugation of the French people. Certainly,

there is a definite correlation between Picasso's adoption of a particular technical style and the appearance in his life

of each new successive lover: Olga is painted in a pictorial language that is cool and neoclassical, while the depiction of

Marie-Therese is surreal and organic and that of Dora Maar is angular, acidic, and deeply disturbing. Interestingly the amazon-like

nudes that represent his second wife, Jacqueline Roche, function as an amalgam of cubism and monumental neoclassicism based

on Goya’s Naked Maya.

Whatever the case, Picasso comes over as a being governed by contradictions, "a twofold being" endowed with a dual vision

that forever engenders a multiplicity of images. Equally telling in this exhibition, especially in the portion devoted to

the post-cubist era, is Picasso’s need and ability to juggle particular styles or techniques. Painting becomes a set

of visual languages based on signs, which Picasso combines and recombines at his ease. Throughout the exhibition we see Picasso

shuffling quasi-representational and cubist styles and their schematic modes of presentation, even playing one against the

other in the same painting. This is apparent in the last version of Women of Algiers where the woman on the left is

partly painted in a naturalistic Matissean style while her companion is subjected to a cubist analysis. This figure, that

like many of his nudes, has as its aim to create a coincidence of front and back which, though conceptually rational in its

striving to present a maximum amount of visual information, necessarily results in deformation. Les Demoiselles D’Avignon,

painted in 1907, exhibits very similar properties, with figures on the right and left sides painted according to conflicting

visual schemata. This, as can be inferred from Picasso's frequent notations, demonstrates that he sought to restore to cubism’s

two-dimensional unfolding of solids a lost sensuous and sculptural presence. (For a truly magisterial exposé of this phenomenon,

read the essay by Leo Steinberg entitled "The Algerian Women and Picasso at Large" in his book Other Criteria.)

This very fact that Picasso could not be confined to one style at any one period and that his facility took him in very different

directions so that there was never one overarching trajectory guiding his work argues, I think, in favour of a chronological

rather than the existing thematic layout of the exhibition. This would allow the basic premise of the exhibition to make itself

felt by showing clearly that Picasso privileged no one exclusive aesthetic ideology, no one formula, no one vision, but borrowed

a plethora of styles from other artists and adapted them to his practice. The one exception would have been his cubist period.

But without Braque, Picasso naturally reverted to representation and the type of draughtsmanship he had been taught by his

father; in fact, he had never really abandoned it. Possibly because of this eclecticism, time and place were deemed very

important to Picasso who insisted on dating most of his work, including his exploratory sketches, explaining, ". . . it’s

not sufficient to know an artist’s work- it is necessary to know when he did them, why, how, under what circumstances."

Picasso’s seemingly innate talent at for appropriating pictorial styles is already indicated in the very first room

of self-portraits. We are told that most are viewed through the lens of traditional or modern masters, and in the majority

of cases this makes good sense. An early Goya inspired Picasso is followed by Yo Picasso, a Lautrecian/Munch inspired

self-portrait in which the artist brashly looks down on the viewer, his face exuberantly lit up from below. Self Portrait

with Palette (1906), with its mask-like face, announces a rejection of the Western canon dependent on the illusionism

of the Renaissance tradition and makes this move into the pre-cubist period via Gauguin, while In the Garden refers

in sorrow to the passing of his arch rival Matisse. When the Galeries nationales in Paris hosted the related exhibition Picasso

et les Maitres at the Grand Palais (6 October 2008 - 2 February 2009), the original old masters were included to accompany

each painting. Since the National Gallery has not followed suit, the links are often tenuous and seem, as in the association

of The Kiss of 1969 with Henri Rousseau, to make little sense. It seems much more probable that Picasso’s inspiration

comes not necessarily even indirectly from Rousseau but directly from Hollywood and the big black and white screen. In the

absence of the originals which may have furnished Picasso’s inspiration for a particular painting, the spectator falls

into a shallow game of "spot the likeness" that detracts from a deeper reading of Picasso’s explorations.

It is therefore when the viewer begins to realise that apart from the cubist period when Picasso was like a mountaineer tied

by his waist to Braque--and this must be why of all Picasso’s oeuvre cubism, his most significant breakthrough, is nevertheless

the least represented--Picasso never desisted from annexing and combining thematic and compositional elements from the traditional

and modern art worlds, that the exhibition begins to make more sense. This dual movement of looking back and simultaneously

looking forward, going forward by looking back, underpins much of Picasso’s prodigious output as he reworked traditional

genres such as the nude, still life and portrait. To this extent, Picasso remains part of an ongoing artistic tradition based

on homage and challenge that has, ever since the Renaissance, attempted to reinterpret past masters, reiterating given themes

in a new pictorial language of formal and schematic invention.

|

| Pablo Picasso, Male and Female Bathers, 1921. Courtesy: Nahmad Collection, Switzerland. |

In this light, Picasso's realism takes on a new breadth of meaning. The period after World War I is dominated by virtuoso

Ingresque portraiture, which includes the cool detached appraisals of his wife Olga, but also by monumental neoclassical nudes,

which share space with a subdued and tamed cubism in which ambiguity has been replaced by Matissean decorative effects. All

of these phenomena share an affiliation with a marked return to order after the heady days of cubist deformation. Thus, the

monumental amazon who is the subject of Large Bather (1921) and attributed to the influence of Renoir, who died in

1919, seems to call a halt to cubist experimentation by embodying a classical sense of order. But it would be over simplistic

to confine influences to one particular painter especially when other extra aesthetic and autobiographical aspects are significant.

Picasso’s marriage to Olga Khokhlova in 1919 and the birth of their son Paulo in 1921 represented a conscious return

to order on Picasso's social and career fronts, one which mirrored the retour a l'ordre happening in France at large. Picasso’s

annexation of territory belonging to past masters cannot be divorced from his own personal and artistic narratives any more

than it can from political issues. His art inevitably mirrored his life, representing an intensification and expression of

his celebrations and tribulations, which come to a climax with Guernica in 1936, when art and life intertwined with

the inexorable rise of fascism.

Realism also begins to jostle with sur-realism, a term which originated with Apollinaire but which Picasso claimed as his

own in opposition to André Breton’s Surrealism. Despite being elevated to the virtual status of surrealist sainthood

by Breton, Picasso rejected the notion of art created via some unconscious avenue, the artist for Breton merely a recorder.

For Picasso, not only was the artist a prime site of experience, but art was a relay of his own sensuous and impassioned reality,

illuminated as it were from the inside. The deep comfort of sleep (as opposed to the tumultuous dream states celebrated by

Breton) as a turning away from the world and entering into a realm of inner sensation is what Picasso beautifully conveys

in his Sleeping Nude with Blonde Hair (1932). This is the somnolent form of Marie-Thérèse, clothed only in Matissean

arabesques in a reworking of Ingres’ odalisque, depicted as a progenitor of life, her pregnant form replete with a hidden

dream of domestic bliss with Picasso that was never to be realised. Nude Woman in a Red Armchair belongs to this same

family of sur-realism. This, a period of relative calm, was overtaken by the Spanish civil war, the continuing breakdown of

his marriage to Olga, his secretive affair with Marie-Thérèse, and the addition of first Dora Maar and then Françoise Gilot

to his array of women, all of which contributed to the expressive density of his work. Several of his wartime still-lifes,

such as Flayed Sheep’s Head (1939) or Skull, Sea Urchins and Lamp (1946) can be read allegorically as

referring obliquely to these various attachments. But it is, of course, in Guernica that the personal and the political,

and realism and the distortion associated with cubism, meet with the greatest impact. The closest we get to this explosive

energy in this exhibition is a much later work, a monochromatic painting based on Poussin’s and David’s Rape

of the Sabine Women, a devastatingly terrifying image of violence and terror.

The Portrait of Jaime Sabartes as a Spanish Nobleman and Picasso’s self-portrait Man with a Straw Hat and

an Ice Cream Cone are paintings of the late 1930s. Both allude to Velazquez and Van Gogh, artists Picasso admired, but

in a semi-playful manner. It is not till the late 1950s that he embarked on a much more self-conscious project that involved

a metamorphosis of the old masters by taking as his framework specific iconic masterpieces that would have been instantly

recognisable to the art loving public. In this period Picasso does more than just cite references to past masters--he takes

on a particular composition as the basis of his own stylistic and technical reinterpretation. He had already attempted a variation

on the theme of Manet’s Picnic on the Grass but it had failed to elicit what he wanted, namely inspiration. It

was the death of Matisse in 1954 that acted as a real catalyst; choosing Delacroix’s Women of Algiers, he set about

interpreting it in the manner of Matisse, having observed, “When Matisse died, he left his odalisques to me as a legacy.”

The result was a work encompassing fifteen canvases in all, based on two separate Delacroix paintings of a harem. Picasso’s

reworkings of the relationship between the four women attest less to his taking on Matisse’s orientalism than to the

cerebral nature of his analytic skills as he pulled the figures this way and that in an effort to integrate them into the

picture plane whilst conveying a maximum of three dimensionality using the conflicting visual languages of cubist and perspectival

spaces. But Matisse is there in the presence of both the odalisque and the sleeping blue nude, the latter a reference to Matisse’s

fauvist Blue Nude of 1907. It is also the blue sleeping nude that undergoes the most extreme manipulations as her body

is literally opened up and twisted in all different directions rather like an origami doll. Picasso’s homage to Matisse

continued in a series of portraits of Jacqueline as an oriental odalisque, dressed and undressed save for a turban, a part

she did not appear to relish in the least but which seems to have afforded Picasso some amusement.

This dialogue with the old masters continued with a sequence of sketches around Las Meninas by Velazquez, Picasso eventually

creating 45 canvases the majority of which were based on a single figure such as the little infanta. Most of these paintings

exaggerate Velazquez’s original colour schemes but the main painting on display at the National Gallery is one from

which all colour has been expunged so that we are left with a monochrome grisaille. It’s an extremely curious homage

to which more than one critic has ascribed hostile motivations, though more perceptive ones have interpreted the giant figure

of Velazquez as a mode of reparation to Picasso’s own father. This is John Berger’s contribution from his book,

Success and Failure of Picasso: “It may be that as an old man Picasso here returns as a prodigal to give back

the palette and brushes he had acquired too easily at the age of fourteen.” It was, after all, Picasso’s father

who had first introduced his son to the painting in the Prado.

In 1961, Picasso returned to Manet’s Picnic, creating 92 drawings around the painting. He does not seem to be

engaged in the cerebral exposition he undertook with The Women of Algiers, though it may be that he was exploring the

difficulties attached to depicting figures in a landscape in terms of figure/ground integration within a cubist space, while

at the same time using his own personal cast of characters, Jacqueline for instance, as Victorine, Manet’s favourite

model. Perhaps Picasso recognised Manet’s weaknesses as his own, namely the difficulty Manet had in inventing compositions

but also the difficulties he underwent prior to being recognised as the first modern artist. The studies ultimately yielded

a series of cardboard cut-outs which were eventually cast as sculptures for the Moderna Museet in Stockholm where they have

acquired a regal ease of presence they do not have in the original variations. During the last years of his life, Picasso

no longer immersed himself in specific problem paintings though he continued to look to the past for inspiration as seen,

for instance, in his series of musketeers which are reminiscent of figures in both Velazquez and Rembrandt.

In 1946, Picasso presented several paintings to the French state. Prior to their being permanently housed in what is now the

Pompidou Centre they were hung in the main galleries of the Louvre, first among the French masters, then among the Spanish

beside Velazquez and Goya. This caused Picasso an understandable degree of anxiety, but he eventually regained his confidence

and was said to exclaim, “You see it’s all the same thing! It’s the same thing!” The public at the

National Gallery was not really able to gauge their own response to this declaration, since the originals were not hung alongside

the Picassos. Some critics thought this was an improvement; others did not. It created an exhibition totally devoted to Picasso’s

paintings, some of which held their own in this "musée imaginaire," while others did not. What we probably also needed to

see, especially in the last room devoted to the old masters, to better appreciate Picasso’s degree of inventiveness,

are at least some of the innumerable sketches that Picasso worked on in his effort to claim pride of place among the old masters.

Now that Picasso has been recognised as a modern master and his work is no longer confined to the Tate but has been displayed,

albeit temporarily, in the National Gallery, it could be instructive to carry on the same game and consider which 20th century

artists would be displayed next to Picassos. Bacon, early Pollock, and Guston come to mind, but I’m open to other suggestions

so that the challenge is no longer confined to the past but represents an ongoing revaluation in terms of Picasso’s

own afterlife within the contemporary imagination.

Anna Leung is a London-based artist and educator now semi-retired from teaching at Birkbeck

College but

taking occasional

informal groups to current art exhibitions.

The exhibition Picasso: Challenging

the Past was at the National Gallery, London, from 25 February – 7 June 2009. For more information, visit www.nationalgallery.org.uk.

|

|

|