|

|

|

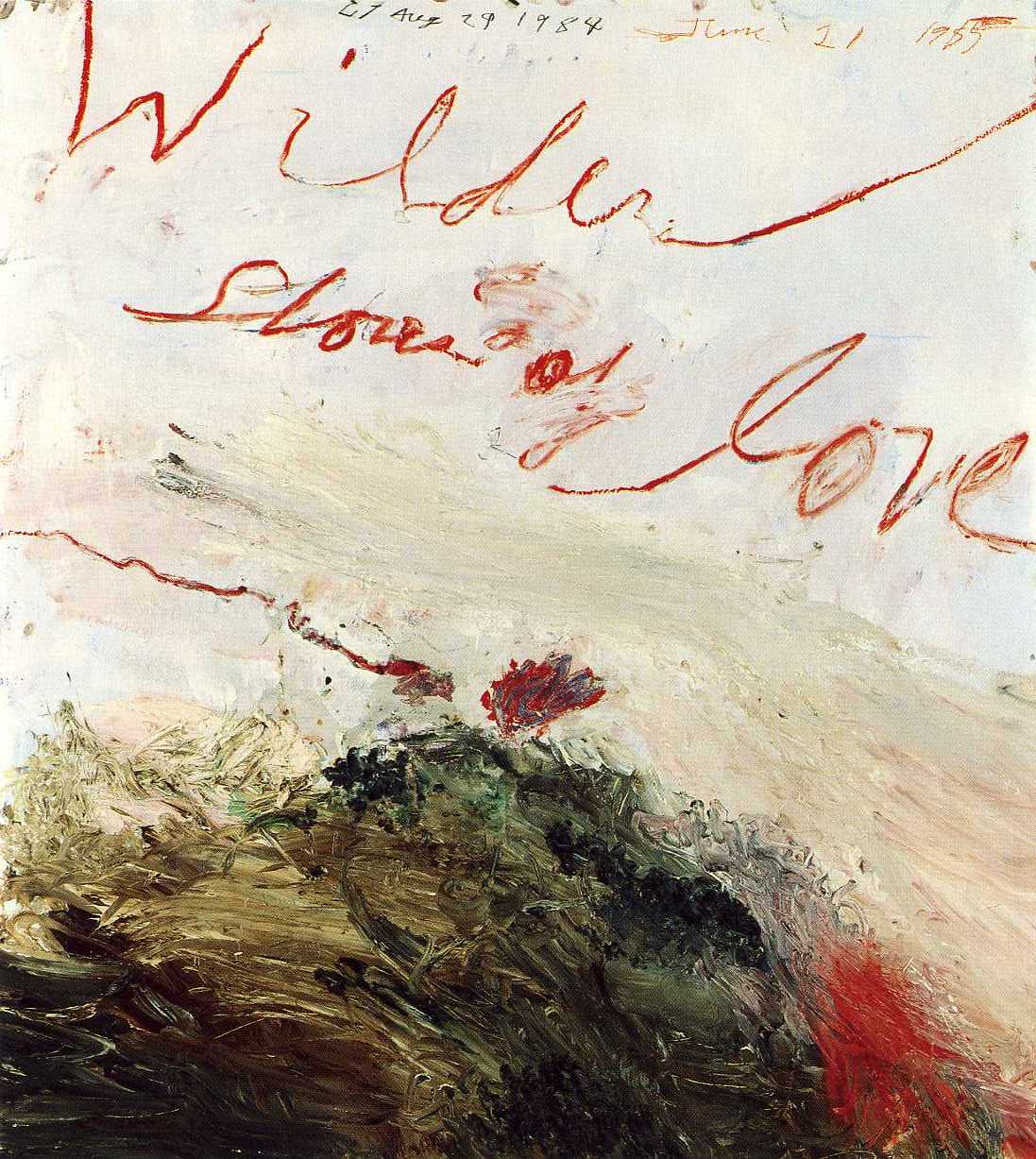

| Cy Twombly, Wilder Shores of Love (1985). Private Collection. |

Introduction

by Deanna Sirlin

Editor-in-Chief The Art Section

Welcome back to the September issue of The Art Section. We commence this issue with Londoner Anna Leung on the Cy Twombly

exhibition at the Tate Modern (which will close shortly). Twombly, who turned 80 this year, is an artist who in some sense

bridges the pond between American Ab Ex and a Euporean sensibility. His poetic paint and text, combined with his palette of

grays and whites punctuated by bursts of rich color, are given a noteworthy consideration here. A way of reading art is presented

by our Italian correspondent, composer Giuseppe Gavazza, who significantly hails from Turin and teaches in Cuneo, where Carlo

Petrini, the founder the Slow Food Movement, was born. Giuseppe gives us his treatise on art as a parallel to this global

gastronomic movement. And we have a recollection by Larry Jens Anderson of the Atlanta-based artist group TABOO, active from

1987 to 2000, of which he was a founding member. I miss these artists very much: they made me laugh when they were here; they

made me cry when three of them left us. Michael, David, and King, you are part of us here in Atlanta, and it is with deep

fondness and appreciation that we remember you.

All my best,

Deanna

www.deannasirlin.com

|

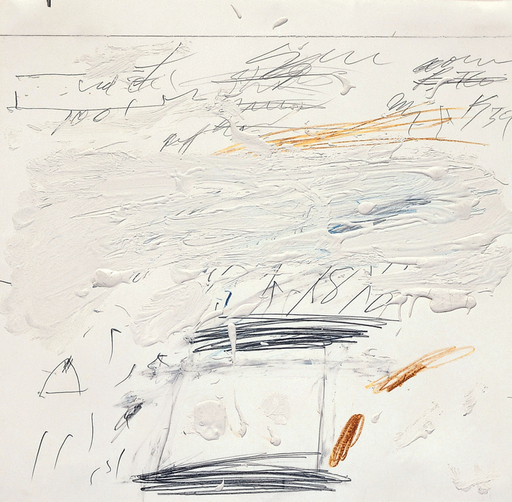

| Cy Twombly, Poems to the Sea (1959). Dia Art Foundation Collection. |

Cy Twombly at Tate Modern

by Anna Leung

For myself the past is the source. . . . I’m drawn to the primitive. . . .

-- Cy Twombly, 1952

It must have seemed perverse. At the very point when America was securing for itself hegemony over the visual arts and as

the centre of the art world moved from Paris to New York, Twombly married well and chose Europe. In 1957 he moved to Rome

where he still lives. While most American artists looked for inspiration in contemporary popular culture Twombly looked to

the ancient world, its poetry and its mythology as the focus for his cryptic calligraphic canvases. When most self-respecting

ambitious avant-gardist artists were turning away from the high rhetoric of Abstract Expressionism, Twombly was perhaps revealing

its concealed narrative impulse.

Twombly was born in 1929 in Lexington, Virginia though his parents originally came from the North. Cy was his father’s

nickname. In 1951, after studying at the Boston Museum School and at the Arts Students League in New York, Twombly studied

under Robert Motherwell, the most erudite and cultured of the Abstract Expressionists, at the Black Mountain College, North

Carolina. His experience at Black Mountain --which he shares with his contemporaries, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns

who initially persuaded him to join them there--may be one of the clues to his paintings, for the college represented a unique

communal project in which artists, writers, poets and music makers all working in various experimental media came together

to share and build on their innovative ideas. It was in addition an important centre for the transmission of Bauhaus theories

and practices. Josef Albers, a key figure at the Bauhaus who had fled Nazi Germany to take up a professorship at Black Mountain,

emphasized exploration of basic materials and making by doing that placed less emphasis on assertive individualism or self

actualising gesture than on chance’s randomness. Equally significant then was the willingness to preserve trial and

error as part of an accumulation of traces or palimpsest of marks that generated the completed work. All these factors both

relate Twombly to, but also differentiate him from, Pollock. For whereas Pollock’s gesture or energy field paintings

are made up of an all over lattice of marks, scrawls and loops Twombly’s canvases are more formal in that that empty

space is critical to his sense of composition. Indeed he sees himself as a formalist rather than a colourist and this is upheld

by his sculptures.

Twombly may at first sight seem out of synch with his contemporaries. He is not part of the Pop and Minimalist mainstream.

He may seem elusive and difficult to categorise and yet, as we begin to study and analyse his canvases, we see enacted again

and again a major and not unfamiliar painterly aim of expressing abstract ideas through the juxtaposition of figurative elements

on the canvas. We see too that his artistic forebears are the Fauvists and Surrealists; not in terms of colour (though the

Ferragosto Series, from the 1960s, especially the last one in the series, deserves the designation as fauve = wild

painting and is heavy with actual colour pigments) nor in terms of surrealist dreams of psychic and political freedom. Rather,

Twombly is fascinated by language and its beginnings when writing and imaging are not differentiated. He explores the territory

of children’s calligraphy, the primordial dis/order of expression which is the equivalent of pre-linguistic babble,

mark making that consists of primitive scribbling, repetitive sign making as well as vehement stabbing and marking the paper

or support. This is a language of marks that is haptic rather than optical and which represents a search for the primal beginnings

of both visual and verbal impulses. It is impure and cack handed, often favouring the smear over the fluent brush stroke.

It is this that relates him to the Fauves who insisted on deskilling the artist, sacrificing artistic competence for expressive

vitality, and to the Surrealist method of automatism by which the operations of the conscious mind are purposely aborted.

Indeed Twombly resorted to drawing with his left hand in order to slough off his artistic sophistication and regain a degree

of authenticity and innocence. All this alerts us that Twombly belongs to the primitivist impulse that characterised so much

of twentieth century modernism, including Klee who from the beginning exerted a strong influence on Twombly: Min-oe

(1951), painted at Black Mountain College, is an example.

Twombly’s early compositions begin with this exploration of a childlike scrawl that constitutes the foundational unit

of pictorial meaning. In addition, these wandering lines represent the search for a meaning that cannot be visually defined.

They relate not to resemblance but to deeper symbolic needs. This series of paintings, made up with pencil, crayon and white

paint, which have been incised with varying degrees of pressure in a zero degree of drawing-cum-writing often yield a strange

and compelling beauty. This said, it must also be pointed out that their content is often vulgar, crass and gross in its sexual

explicitness, its vernacular excremental and bloody, and this is what tempts critics to describe such works as The Italians

and The Empire of Flora (both 1961) as synonymous with graffiti. Graffiti has a potentially violent subtext; it is

a form of action, and it is for this reason that Arthur Danto argues (in The Madonna of the Future) that these compositions

have a “demotic” (colloquial) quality. There is, then, despite a certain beauty, nothing purist about them and

it has been suggested that it was Clement Greenberg’s doctrinaire aesthetic politics, which allowed only the purely

optical abstract colour field painting to dominate the art world, that persuaded Twombly to move to Italy. For Twombly’s

compositions that retain vestiges of symbolic figuration represent something inconclusive and vulnerable, as the mark’s

expressive potential seems to oscillate between the made and unmade, the destructive and the creative.

The inclusion of the written word adds both complexity and confusion, as do the titles, if taken literally. For instance,

where are “the Italians”? On the other hand, it’s almost impossible not to engage with the written word;

names especially are porous with meaning. Apollo, for instance, immediately evokes a poetic dimension summoning up vestiges

of a lost classical past that has a melancholic resonance but which at the same time is both sensuous and highly charged sexually.

And it not just the name or text but the way the letters are loosely scrawled over the canvas that evokes memory and history.

The letters are crooked or crowded, the lines of poetry taken from Mallarmé or Baudelaire, Rilke or the Greek poet Seferis,

tend to be uneven. This strong humanist focus on the great works of literature, poetry and myth reengage Twombly with the

first generation of Abstract Expressionists. But rather than sequestering his painting within Abstract Expressionism’s

metaphysical sublime, Twombly’s calligraphic marks come closest to de Kooning’s graffiti-like notations and to

Motherwell’s collages. When Twombly celebrates the classical and the “Mediterranean effect” it is not the

effete Victorian worship of the antique but is closer to a much darker Nietzschean interpretation of the barbaric vitality

of the classical spirit. For Twombly, the historical cycle of empires with their recurrent narratives of victors and vanquished

is ever present to remind us of hubris and the ultimate ephemerality of life; in 1977-8, he produced Fifty Days at Iliam

a series of ten collages that constitutes a single work based on the sacking of Troy. Bacchus, Psilax, Mianomenos (2005)

looks once again to Homer’s Iliad as America continued to be entrenched in Iraq.

In the late 1960s Twombly abandoned colour and went in a completely different direction, This move towards minimalism was

probably prompted by a disastrous show at Leo Castelli’s gallery in 1964. At a time when a minimalist puritanism reigned

in America his exuberant, luscious Roman scribble was not considered to be in good taste. It all seemed too elegant, too European.

His two versions of the Treatise on the Veil (1968 and 1970) represent an attempt to redress the balance and move into

the minimalist sphere. Like many other artists, including Jasper Johns and Gerhardt Richter, he produced a series of (funereal)

gray paintings. His were reminiscent of blackboards annotated with rectangles that seem to focus on the function of the line

to measure. This however was the only time Twombly attempted to make himself accountable to fashionable and critical opinion.

He returned to his wavering calligraphic script, and to his the sculptures on which he has worked sporadically throughout

his career. Made of humble bits and pieces, cardboard boxes and tubes, plastic flowers, and other bricoleur elements, these

are almost invariably subjected to white paint or plaster making for extremely elegant, spare pieces that carry much symbolic

freight. They often seem to convey a language of mourning making them testimonials to the passing of time and the vulnerability

of our existence.

Possibly Twombly’s best known paintings are his two series of Four Seasons (1993-4). Each season represents a

different stage of life but as a unity they represent the primordial cycle of life and death, recreation and destruction that

is reinvested with an almost overblown, overripe richness through the pungency of his symbolic figural imagery. The canvases

are mostly white but with flower splotches of colour, red and yellow Egyptian boats for spring, harvesting of the wine for

the autumn.

Not all of Twombly’s paintings are successful and it’s sometimes tempting to ask how much credence to give to

the poetic text wandering drunkenly over the canvas, or to the lettering that looks more like a doodle, or a recalcitrant

child’s attempt to master joined up script. In all this furore of strokes and marks one cannot help seeing what one

is predisposed to see and his drawings revert to mere notations which, if found elsewhere, would have little more than anthropological

value. But by some strange magic Twombly is able, more often than not, to generate a highly differentiated pictorial language

of condensed form that captures within the space of one canvas a multitude of seemingly opposed forces, rational and sensuous,

elegant and crass, restrained and intemperate. Moreover, despite his openness to random procedures this calligraphic style

of marks, fleeting images, accretions and erasures is based on prior formal organisation. The palimpsest this creates is made

up of ambiguous layers of meaning that resist closure and in this way provoke or precipitate a distinctive meaning that alerts

each of us simultaneously to the pleasure of life and to the passing of time.

For more information on Cy Twombley at Tate Modern, London, please visit the Tate website.

Anna Leung is a London-based artist and educator now semi-retired from teaching at Birkbeck

College but taking occasional informal groups to current art exhibitions.

Slave to the Rhythm

In Praise of Slowness: steps to an ecology of AV perception

by Giuseppe Gavazza

1 – Another AV Festival: a catalyst for some considerations

Between the minutiae of the exhibition NanoArt: Perceiving the Invisible and two cyber colossal movies (the final cut

of "old" masterpiece Blade Runner (1982) and the fresh 100% digital old hero-epic Beowulf deeply expanded in

space with 3D glasses) my eyes are drunk on images and colors. I'm getting out of VIEWFest 2008, Torino (viewfest.it) after a fully immersive weekend. If my eyes are drunk, my ears are drunker because of low-fi audio equipment. [*1]

and the fast and furious rhythms of most of the works.

2 – Allegro furioso

As in Grace Jones's 1985 hit "Slave to the Rhythm," moreand more we must:

Never stop the action,

Keep it up, keep it up,

and ...

Breath to the rhythm,

Dance to the rhythm,

Work to the rhythm,

Live to the rhythm,

Love to the rhythm,

Slave to the rhythm

Are we all born to run, run, run, run, ... on the fast car of this earth? Till we die, exhausted?

(The gorgeous video for this song was used to advertise a French car whose name - CX - is the acronym of the coefficient for

aerodynamic drag: beautiful and speedy, well tuned in aesthetic/engineering polyphony).  3 – Slow Life: slowness as nourishment and beauty,

3 – Slow Life: slowness as nourishment and beauty,

Food is deep culture and art is food for human beings. Please don’t eat automobiles.

One of the more interesting and intelligent projects and concepts I know is Slow Food. Born in the Turin area – in the beautiful hill country of the Piedmont – Slow Food is, as you can read in the

website:

“… a non-profit, eco-gastronomic member-supported organization that was founded in 1989 to counteract fast food

and fast life."

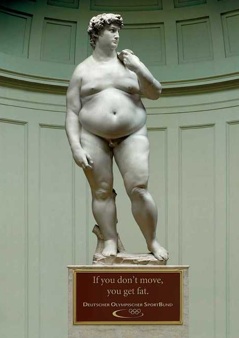

In the McDonald’s era, one century after Futurism’s utopian shout to the brave new world of the beauty of speed

(and of violence and war) I reflect on the beauty of slowness. In 1909, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, in his “Manifesto

of Futurism,” wrote:

“We declare that the splendor of the world has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing automobile

with its bonnet adorned with great tubes like serpents with explosive breath ... a roaring motor car which seems to run on

machine-gun fire, is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.”

The Victory of Samothrace is more than slow; it is motionless (and eternal). Apparently immobility isn’t good

for health in our slim-fast-body-machine oriented world as indicated in that smart advertisement with an obese Michelangelo’s

David statue and the motto: “If you don’t move, you get fat.”

Fast or fat? Is that the question?

Lack of speed isn’t the same thing as immobility and slow doesn’t necessarily mean lame.

I envision a wise, slow world, neither senescent nor weak, simply a good, different way to live, not just survive, without

succumbing.

As we can read in Chronicle of My Life by Igor Stravinsky: “Music exists with the critical aim to establish an

order in things, comprised - in particular - of coordination between man and time.” (1936)

Music is the metronome of human life. [*2]

Don’t run, please: I like that Grace Jones hit just as I like much of the last decades’ quick and frenzied music.

I enjoy dancing to them for whole nights, but I ask: where is the time for the homeopathic music of my beloved Morton Feldman

(not to be found on the hit parade)?

Where are the (internal) time and the space for the Rothko Chapel?

For the chapel Mark Rothko conceived in 1971as a big canvas, Morton Feldman composed a beautiful piece with the same title.

The Rothko Chapel is a building, a space, a composition, a suite of paintings, a visual art piece, a place, and an interior

experience.

It exists in the heart of Houston’s museum district - not by chance - very close to Richmond Hall which houses an important

Dan Flavin light installation.

Mark Rothko, Morton Feldman, Dan Flavin: light, color, and sound out of time….

No rhythm, no slavery?

Great events linked to Slow Food are Terra Madre (Mother Earth) and CittàSlow (Slow Cities). The new WCF (World Calmlife Fund: subscriptions are open) wishes to propose a SlowArt Section in Slow World activities:

music and visual arts are food for human life, and the use of art and music to counteract fast life would be really sane,

for all of us and for the planet herself.

Slow up to a new S family: sPod, sLife, sWeb, : sNoMcD, sMusic, ssssssss ….

4 – Some final considerations about ViewFest 2008

Coming back to the catalyst for this meditation, I don't know whether special attention was given by VIEWFest 2008 to

breathlessly rhythmic works, if they really are the most numerous or significant, if brevity demands velocity (a clichéd equation),

if authors are quite nervous, or if the public asks for such speed as a doping, like in sports or TV shows.

Mine is merely a general cogitation, not a qualitative judgment: some of the works shown at this Festival are astonishing

(such as some Siggraph selections or the well-known, wonderfully short (and often slow) animated films by Pixar, and many

others set to Adagio or Calmo on the metronome). But most are frantic & adrenergic AV stimulations of our senses.

Against this feverish panorama the works of Lorenzo Oggiano stand out like a WCF-protected archipelago of quiet islands. The

video photographic cycle Quasi-Objects proposes a Quasi Second Life at infinitesimal scale: totally artificial 3D modeled

objects appear as microscopic organisms slowly evolving, pulsing, living, breathing, dancing.

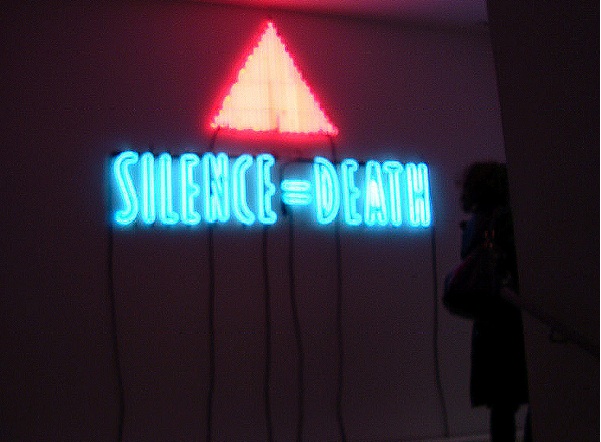

In my first contribution to The Art Section, under the title "Ears Wide Shut" I wrote: “Years ago, under a similar skyline, on a subway’s wall I read: “silence = death.” Weeks

ago, I found the same phrase in flashing neon on a staircases climbing to New York’s New Museum of Contemporary Art,

and I thought again of the Chinese adage: “If what you have to say isn’t better than silence, then shut up.”

Slowness=Life.

|

| New Museum of Contemporary Art, New York. Photo: Giuseppe Gavazza, 2008. |

[*1] Once more, I regret the negligible attention given to sound diffusion. Cinema is mainly image, of course, but

an important institution like the Museo Nazionale del Cinema cannot, in my opinion, present in an international festival (ViewFest

is the continuation of the ten year-old ResFest) an anthology of short recent video mostly based on music or with a

remarkable soundtrack (like the Chris Milk music videoclip retrospective) with an audio system of such poor quality. Low

fidelity and high distortion made immersive listening truly uncomfortable.

[*2] A good reference is Mark Johnson’s illuminating book The Meaning of the Body: Aesthetics of Human Understanding,

2007, especially the chapter concerning music.

Giuseppe Gavazza, a composer who lives and works in Turin, Italy, is a frequent contributor to The Art Section.

www.giuseppegavazza.it

Images (clockwise from upper left): Best In Show (1994); TABOO memorabilia; Confessions (1995); group portrait

of the TABOO collective; Johnny Detroit's Brunch (1990); TABOO's Olympic T-Shirt (1996). Photos: Larry Jens Anderson.

A Remembrance of Things TABOO

by Larry Jens Anderson

TABOO was an accident. TABOO, the Atlanta artist collective, started with a group of artists who shared mutual respect for

each other’s work but did not know each other. They met fortuitously at an opening and decided to get together to have

some wine and discuss art. The gathering quickly disintegrated into a bitch session about the lack of edge in the Atlanta

art scene. The eight artists present each talked about pieces of their own that were considered too taboo to show in Atlanta.

It was 1987, a year when AIDS was a major topic of discussion, ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power) was in angry high

gear on the political scene; it was President Reagan’s time in office; political correctness was the order of the day;

the Christian right was feeling its power; and artists were suffering from put-downs by the NEA and Senator Jesse Helms.

Each of those at this initial meeting was over 30 years old, an active working artist, and not shy. Rather than just bitch,

they decided to do something about their complaint.

A look at the calendar for 1988 revealed that Good Friday fell on April Fool’s day, on a full moon, in a leap year.

The timing seemed right. They all realized nothing would happen without a space to show in, preferably free. King Thackston

had a real estate friend who offered a space and they were set. Two of the artists decided the concept was too risky for

their career and the remaining six began to plan. The decision was for each to invite another artist, doubling the number

in the show. In addition to the work presented, the group added an element that would turn the opening into an event, something

that became fundamental to the planning. The invitation requested attendees bring an object for the fetish pole. The overloaded

fetish pole was given to a grateful Howard Finster.

The opening was a big success; several hundred came. Two comments in the guest book presented unexpected challenges: “What

is TABOO going to do next?” and “This isn’t so taboo!”

TABOO as a noun, a group, was born. Until that time they were just a loosely organized group of professional artists putting

on one exhibition of taboo work that challenged the system.

Over the years the group morphed into a curatorial, art producing, renegade but very professional group of four gay men: Larry

Jens Anderson, David Fraley, King Thackston, and Michael Venezia. Each member had an active career, but the mindset that

happened when all got together was unique. It included poking fun at art through irony, utilizing camp humor, prodding sociological

phenomena, and encouraging many artists invited in to stretch.

There were only three TABOO rules. Make it an event! Always use some French in the artist’s statement. Only art that

received unanimous votes from all four members got into any show.

In 1990, Good Friday fell on Friday the 13th, and the second exhibition, The Cross Show, was conceived. TABOO thought

being crucified was a turn of bad luck. The three-day exhibition showed only work in the shape of a cross. Participation was

open to any and all for a $15 entry fee. To enter the gallery, attendees had to walk under a ladder and were confronted

by other bad luck omens. The Cross Show was a big success and TABOO was developing a reputation for producing challenging

and entertaining exhibitions.

Johnny Detroit’s Brunch was a celebration of male proportions on the ten-year anniversary of Judy Chicago’s Dinner

Party. It answered the challenge that we weren’t taboo enough. The idea came from a comment by Joeff Seagis during

that first evening discussion, “Ever since Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party I’ve wanted to do Johnny

Detroit’s Brunch.” In the politically correct atmosphere of the late ‘80’s, an all male exhibition

was 100% wrong. Perfect!

A real challenge was finding a location for Johnny Detroit’s Brunch. No gallery or institution would touch a

concept put together by 5 white guys (TABOO had shrunk). A friend of King’s was running Seven Stages, a theater in Little

Five Points, Atlanta’s bohemian district, and leant their space to TABOO. The 34’ arrow shaped table had six

male honorees on the arrowhead and 12 men down each side of the shaft. The men represented were chosen by each of the 30

artists: Jesus, Greg Louganis, Tarzan, The Three Stooges, Dali, and others were represented. The place settings were consistent

in the number of pieces and size. The general assumption was that there would be plate after plate of penises, but the range

of ideas went far beyond that. Johnny Detroit traveled to New Orleans and Asheville, then died from overwork.

TABOO began to be offered space--no money, but space. The Arts Exchange (in an old school building) offered their gallery

space for December 1991. The look of the converted schoolroom inspired TABOO to limit the scale to 12”, to simulate

classroom-sized artwork. Tiny Xmas Memories: nothing-over 12” came with real limitations: submissions over 12”

would be cut down to size. Two pieces suffered this fate. After all, rules are rules!

For the 1992 Atlanta Arts Festival TABOO curated Angry Love, featuring art made when you are mad at love. This was

their first nationally advertised exhibition. The festival theme was pushed by putting up four large-scale carnivalesque

banners produced by the TABOO members, blinking lights, and a tent like entrance in vaginal pink.

In 1994 TABOO was again invited to participate in the Atlanta Arts Festival whose theme was “Money Changes Everything.”

The result was multi media installation called Best of Show. The TABOO members decided that fame and money were intertwined.

Their premise was the more famous the owner of any object, the higher the value. They created a fictitious gallery to sell

rubber ducks whose ownership was by the likes of Mapplethorpe, Dali, Gandhi, and so on.

Next came an invitation from Chris Scoates, then the director of the Atlanta College of Art Gallery. I995 was height of trashy

afternoon talk shows hosted by the likes of Jenny Jones, Oprah, and Jerry Springer. TABOO jumped on the bandwagon and created

a show where the artists were juried in by the quality of their confessions. Creative Loafing, an Atlanta-based weekly newspaper,

chose Confessions as the “Best Art Show of the Year.”

As the ’96 Olympics closed in, it became obvious that there was no exhibition of Atlanta artists planned for the Cultural

Olympiad. Debra Wilbur, then the director of the Chastain Gallery, agreed this was not right. When she inquired what TABOO

might do, Gone With the Wind: Fabrication and Denial of Southern Identity was the answer. The resulting exhibition

included political, humorous, hard-hitting, beautiful, tender and angry art about the Southern experience. The opening was

packed with attendees enjoying each other, the art, watermelon, RC Cola, Moon Pies, and bags of peanuts. The show garnered

praise in New York’s Village Voice and was singled out as one of the best exhibitions of 1996, along with the

Rings show at the High Museum of Art.

Vaknin/Swartz Gallery invited TABOO to do a December show. Testosterone: Christmas Balls was the first time the group curated

in a commercial gallery. It included artists chosen from throughout the US.

For their last production, Requiem at The Nexus Arts Center in Atlanta, TABOO placed in an outdoor courtyard a hearse adorned

with a large banner declaring it the “Pace Car For The Millennium.” Mozart’s Requiem played at full

volume, the gallery entrance was draped in black, and the four members of TABOO were depicted as the four horsemen of the

apocalypse. It signaled TABOO’s end after 11 years and was a send-up of the ridiculousness of the fuss made over Y2K,

the transition from 1999-2000.

In more than a decade of working together, the members of TABOO created only one collective art piece, Best of Show

for the 1994 Arts Festival of Atlanta. Most of their efforts were curatorial. But they also did interventions, lectures,

performances, made TABOO ware, guest appearances, conceptual events, and supported individual members’ shows.

T-Shirts were the major fundraiser. Most corresponded to a show but others were specific to an event (interventions). White

Guys Are Ethnic Too was created to wear to a grant seminar in the politically correct ‘90’s. For the Olympics,

TABOO made four t-shirts that included TABOO with graphics of the Olympic rings and the phrase, Greek Active Artists.

The biggest seller was Buy Art, Not Drugs. The Idea Sale t-shirt was created as an addendum to an ad selling

ideas for artists suffering artist’s block that ran in Art Papers Magazine. The members had individual T’s

for TABOO’s bowling challenge against the staff of Atlanta’s High Museum of Art.

What is TABOO’s legacy? Passion for art was central. Camp humor, a gay sensibility that uses self-deprecation and

irony to have fun with—and make fun of—very serious subjects was second nature to the four members. TABOO often

pointed out the ridiculousness of sacred cows. And they were smart, avoiding the gratuitous (unless it was intentional).

Art can be fun and serious at the same time.

The death of three of the members leaves a gap in the Atlanta art community. Their unrealized work is missed. Their input

into boards and organizations is a big loss. And Larry Anderson misses laughing with his buddies when they were at their most

wicked.

Larry Jens Anderson, who teaches at the Savannah College of Art and Design’s Atlanta campus, is an artist

whose work focuses on human rights issues concerning sexual orientation, the AIDS crisis, death, and religion.

|

|

|