|

|

Introduction

by Philip Auslander

Editor The Art Section

This summer’s issue of The Art Section could perhaps be called our “art-insiders” issue, as all three

articles are from the perspectives of people who have been involved in or looked behind the scenes of various art worlds.

Clear-eyed, they report to us with both enthusiasm and healthy skepticism on what they have seen there.

We begin with The Art Section’s Editor-in-Chief Deanna Sirlin’s interview with Michael Klein, who has had

a distinguished and multi-faceted career as gallerist, curator, and, currently, documentary filmmaker. Klein speaks of how

he came to be interested and involved in art, conveying his passion for that world and its inhabitants. He discusses his work

as a producer of documentary films about artists in terms of a strong desire both to demystify the artistic process for a

general audience and preserve artists’ legacies in audio-visual records.

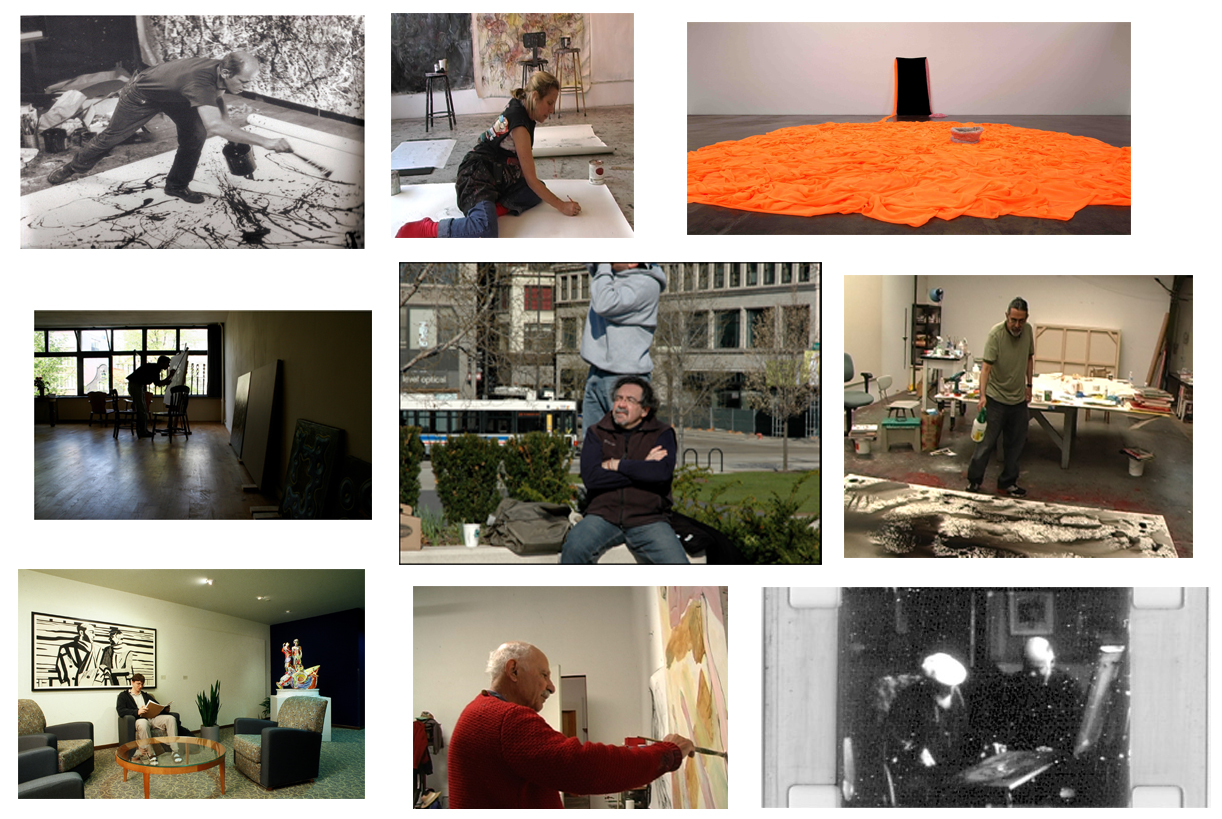

Next up is Andrew Dietz, author of the controversial book The Last Folk Hero: A True Story of Race and Art, Power and Profit

(Ellis Lane Press, 2006), who raises provocative issues concerning the exploitation of folk artists and the question of whether

exploitation is inevitable when art meets the market. We present an excerpt from the book and the author's reading of it.

Finally, Laura Hunt interviews Shane Brennan, Curatorial Assistant at Creative Time, Inc., who was part of the team that presented

Waiting for Godot in New Orleans in 2007. Brennan speaks not only to the poignancy of performing Samuel Beckett’s

bleak vision in post-Katrina New Orleans and the power of art amid devastation, but also to questions arising from the potential

politicization of art.

Have a great summer. We’ll be back with a new issue in September!

All my best,

Phil

www.philipauslander.com

Images:

Beverly Semmes at Microsoft

Cover: The Last Folk Hero Photo: Dietz

Waiting for Godot Photos by Donn Young and Frank Aymami. Courtesy of Creative Time. © All rights reserved

Hans Namuth: Jackson Pollock; Judy Glantzman in her studio; Beverly Semmes: Prairie Dress

Peter Schuyff in his studio; Michael Klein on location; Enrique Chagoya in his studio

Interior at Microsoft, Redmond, WA; Charles Garabedian in his studio; Film still from a Jean Renoir film of Pierre-Auguste

Renoir with his dealer, Ambroise Vollard

Perspective:

An Interview with Michael Klein

by Deanna Sirlin

Michael Klein is a founding partner, with Matt Bertles, of Talking Point Films and, as Michael Klein Arts, is an artist’s

agent and freelance consultant for arts organizations. He is a highly regarded writer, curator, and program director and has

been the executive director of the International Sculpture Center based in New Jersey. Klein has been a regular contributor

to Sculpture Magazine in addition to writing reviews and feature articles for Art in America, ARTnews, and World

Art, among others. Between 1983 and 1997 he was owner of Michael Klein Gallery, New York representing some 20 emerging

and mid-career American and European artists. As an independent curator Klein has organized museum and gallery exhibitions

specializing in contemporary and 20th century art for Independent Curators International; Contemporary Arts Center, Cincinnati;

Contemporary Arts Museum, University of Southern Florida, Tampa; and Arthur Roger Gallery, New Orleans. He served as the first

curator for the Microsoft Corp between 1999 and 2005, directing art acquisitions, commissions, collection management, and

an education program for the company’s 50,000 employees.

Deanna Sirlin, The Art Section's Editor-in-Chief, interviewed Klein concerning his work with artists and his ideas

about life in art.

When you encounter a work of art for the first time, what part of you comes into play --- is

it a more intuitive or analytical experience? How do you judge or experience the quality or greatness of the work?

I think the experience of seeing something new or for the first time relies on intuition and can be somewhat physical. I generally

have a visceral reaction to works and can tell pretty quickly if the work is for me. I sometimes feel that this is too personal

a take on work but, then again, if my reaction to a work is not personal then it probably is not something I'm going to be

all that interested in. Over the years, various friends, associates, and colleagues will call and say, “Oh, I know your

taste, you will love so and so's work” and I get there and it is a huge disappointment…for me, and the artist,

too. Once caught up in looking at something I am interested in I am full of questions, and if I am not interested I usually

just start to pace and I get completely quiet.

There is no accounting for taste and there is no single rule that allows you to guess ahead of time what will or will not

tantalize your eye and interest your mind. I'd like to say that I am open minded but I have seen a lot in the past three decades

and now, from my middle-aged viewpoint, I am less interested in something brand new than in artists who have been working

for years and have either been overlooked or forgotten. For example, it is nice to see Roger Brown with a show in New York

more than 10 years since his death.

And as to the greatness question: I don't know if I can say I can judge that quality but I can discern something remarkable,

something new or perhaps said in a new way. This, I must add, is different from novelty; new for the sake of being new. I

think great works have a lasting quality so that you find yourself returning to look again and again even though you are familiar

with their form or content or both. Some works just haunt you--Brancusi at MOMA; the Gertrude Stein portrait at the Met, or

any number of the Hoppers at the Whitney. Other works you discover at different times of your life. Your eye is awake only

to certain experiences at certain times of your life and you gain visual knowledge over time. As a college student, I had

no idea what Matisse was about; then, one day, boom, it hit me--I saw it and now I look for Matisse works wherever I travel.

On the other hand, I have always loved Caravaggio’s paintings and can't seem to read enough about him. Ironically, his

reemergence as a significant painter only came about the year before I was born, so I am living in a time period when he is

of interest to critics, historians, and the public. A hundred years from now that may not be the case. So greatness is relative;

it depends on more than just what a critic or two may say today or how the market place reacts.

How did you develop your eye for art? What happened in your first encounters with contemporary

art, when you first saw Dan Flavin or Robert Morris, for example?

It really started early in my life with being dragged to museums as a child. We lived on the Upper West Side of Manhattan

and my folks took the Sunday, after breakfast walk from there to the east side. We would walk through the park, then hit the

Met, and I would be walked through gallery after gallery of art. As a child, I just looked and was amazed by the sheer quantity

of works on view and the excitement of people straining to see something, a painting or a sculpture. My mother had lived in

Paris before the war, so she always wanted to look at the French Impressionists and my father had a passion for Chinese sculpture.

By the time I was in college, visiting museums was part of my social life; it was a habit. I would ride up to the Met from

the village on a Sunday afternoon—I was at NYU-- walk the galleries, and then stroll home for Chinese food, another

Sunday habit!

My first exposure to contemporary art came in the form of a class trip to see the 1969 Whitney Annual. There, I was struck

by installations by Dan Flavin and Robert Morris. I had no way of describing what I had seen and think that the experience

of seeing the neon lights of the Flavin and the mirror glass of the Morris just stayed with me. That same summer, I went to

Syracuse University for an art program where I studied photography and also made painted slides which I projected on to walls

to try to emulate the Flavin experience. Only a few years later, when I was in the Whitney Independent Study Program, did

the experience measure up to the experience of talking about art with artists.

I developed my eye over years of looking, and that looking never stops. I love bumping into museum directors and dealers at

museums on a Sunday afternoon; they all know the drill.

In terms of contemporary art—that is, post-war painting and sculpture--a lot of what I have learned is self-taught.

Remember that when I was a grad student in the mid 70s, contemporary art was not even mentioned as a possible course of study.

(And most of the New York institutions that were to feature contemporary art and artists, such as Artists Space and PS 1,

were just getting off the ground.) I gleaned a lot from spending hours in the library. This habit started young; my mother

dragged us weekly to our local library to be exposed to books. I always took out the art books and, of course, the art magazines.

Reading in a library and studying art became something very comforting for me. I haven't lost that desire and even today I'm

always curious about collector's libraries. At grad school, I was offered the job of sorting through a large storage closet

full of contemporary and modern books and catalogues. I sifted through literally hundreds of titles. Part of the deal with

the librarian was that I could keep any duplicates. I looked through catalogues from Germany, Italy, and Spain and organized

the monographs and histories in different boxes so that the important works could be catalogued. From this hands-on research,

I was also able to recommend titles that were missing from the collection.

I never lost my interest in or excitement about art. I think I am naïve that way and, as some people have put it, very idealistic.

But why not; why not hold onto some ideals, things, ideas, and beliefs that guide you in your life, art or not? The world

will never be the way I wish it to be nor will it bend to my wishes or desires, but I can manifest my ideas in certain forms

or directions and so I am happy to do just that for whatever time I have left.

In college, I learned from an amazing group of art historians: Horst W. Jansen, Dore Ashton, Robert Rosenblum, and Leo Steinberg.

Then came the Whitney program and my exposure to more artists from different fields during afternoon lecture sessions—Tricia

Brown and Philip Glass, for example. We were introduced to a variety of artists whose studios we would visit--Richard Artschwager,

Malcolm Morley, and Alfred Leslie come to mind—and to the art world and colleagues like editor Edit DeAk; William Zimmer,

a New York Times critic who just passed away; Barbara Flynn, who is a private dealer now in Australia but had a terrific gallery

in the 80s on Crosby St; and Richard Armstrong, Director of the Carnegie Museum.

Guidance and knowledge came from Martin Friedman, with whom I worked in the mid 70s at the Walker Art Center. He taught by

action and managed to instill in us the ideals of professionalism without giving up a sense of passion, excitement, and curiosity

when it comes to working with artists. He made you think on your feet in the museum, speak from the heart. and write so that

people will read it and grasp your ideas and understand your comments.

Ultimately, I gained a lot from time spent with painters, sculptors, architects and photographers, and other dealers and critics.

Some, I would come to work with (James Casebere, Jackie Ferrara, Matt Mullican, and Pat Steir) while others became friends:

Alice Aycock, Lynda Benglis, Ross Bleckner, Beverly Semmes, Elaine Reichek, Jene Highstein. Others now are among a long list

of victims of the first years of AIDS epidemic: Gary Falk, Ken Goodman, William Garby, James Ford, Paul Thek, while still

other dear friends we/I lost to suicide (Ralph Hilton and Burnett Miller).

The idea of the “eye,” which implies a kind of connoisseurship, seems to be unfashionable

right now, as do such related concepts as taste and beauty in art. Why do you think this is?

Well, the "eye," or connoisseurship, is, of course, a concept that has been expunged from use but still lingers. It really

depends on who is speaking, about what they are speaking, and what criteria they are using to determine their conclusions.

So can someone talk about abstract painting in a different culture or setting using Western values or American values? How

do Western eyes look at non-western art and establish critical values?

Can we trust the speaker, the writer or their conclusions? Ultimately the voice of asking the question is as important as

the question itself.

You have said that risk is important in art. What do you mean by risk? Why is it important?

And how does one recognize it in a work?

Life is certainly not linear, and so there are many starts and stops and, I won't say wrong steps, but change-of-mind steps.

I called my talk “Art is Risk” because it seems to me that, in spite of a growing, buoyant art market, there is

always a risk in putting yourself out for others to see and judge. I grew up at a time when the task of artists was to find

new ways of defining their function and their place in society. Unfortunately, in this society artists still are not decision-makers

nor do they have any political power. The New York Times recently reported the income for professional artists, which does

include architects and designers, was 70 billion dollars in 2005; yet they still function more like consultants or advisors

to programs and projects, indulged mostly, or, in the worst case, odd or unusual guests for dinner. At Microsoft, where I

was the curator between 1999 and 2005, I was aware of the prejudice against artists, aware that the architects assigned to

projects were given carte blanche (they were serious) while art was the suspicious and often times "fun" add-on to a project.

I'm sure at various meetings where I would suggest we bring artists in to review a project, others thought, How could art

be serious and why would we solicit the opinions of artists on solutions for social or technical problems? To this day, when

I hear someone use the word “fun” when describing some exhibition, I see red.

Your TPF films present intimate portraits of artists, allowing their voice to be heard. Can

you talk about it is important that such representations of artists be available?

The idea for making these films comes from many sources. First I am extremely alarmed at the overall lack of knowledge, or

should I say information, about the visual arts. Among the numerous tours I did for Microsoft employees at the Seattle Art

Museum was one of an exhibition of photographs by Annie Liebowitz. I spent some time talking about putting an image together,

describing the differences between foreground, middle ground, and background. After the tour, one engineer came up to me to

thank me and commented that no one had ever explained to him how a picture is put together before. I was astounded, because

here was a very smart man, but his visual vocabulary was nil. And we are a full-on visual culture; you name it and we communicate

it via images. Understanding how and why images are used is fundamental to understanding who we are, how we think, and how

we try to communicate.

So watching a film about an artist working is like watching Julia Child in the kitchen. She demystified the art of French

cooking and also opened us up to experience cooking as an art. It was a form of nourishment, yes, but it also had cultural

and social overtones. Her efforts to explain the elements that make up a classic French dish allowed the American audience

to become familiar with a new language, new tastes, and new cooking skills. From these weekly programs that were aired in

the mid 60s, a revolution was born. As a result of her efforts, we are now a country now that is as comfortable eating any

number of cuisines from Asia, Europe, or California. The same thing can happen, I think, with artists. Not that everyone will

become an artist, but exposure to the experience of hearing AND seeing artists at work in their studios will demystify some

of that activity. These films also document the life of that artist and that moment and they provide some of the vocabulary

that many need in order to ask questions and learn about art. Here is where I am naïve again, but I see the web as one of

the most extraordinary educational tools—reaching around the world in a matter of seconds and connecting millions of

people to a shared experience.

I think it is important to create a portrait of the artist at work because our memory changes over time, and having this event

recorded for future audiences is a key to creating the history of our time. As a student of art history, I was schooled in

the idea of "original" documentation, the papers and records that could substantiate the historian’s claim or belief

or observation. In the same way I think these films are original documents that will one day become part of the archive of

the first decade of the 21st century. As a curator at Microsoft, I was inspired by the questions the employees had about

artists and it was there that the idea was born that creating such documents for the collection's website would be a great

service to both viewer and artist.

How do you think the Hans Namuth photos of Jackson Pollock making his drip paintings changed

the way he was perceived as an artist? What kind of influence do you hope your films will have on the perception of artists?

I hadn't thought of the Hans Namuth photographs in terms of how they changed our view of what the Pollack paintings mean;

I did see these photographs as a precursor, if you will, of what we have in mind at TPF. Obviously. they underscore a critical

idea of the day: that the painter was engaged in the making of his or her painting as a physical act. In the arena of painting,

the painting was a stage, the painter the actor, and the paint the language by which he or she expressed themselves. I think

it literalized the philosophical position that painting is an act of being, something for the public to witness firsthand.

The drama of these now classic portrayals of an artist at work also underscores the myth of the artist as hero, or at least

the heroic Jackson Pollock, triumphant, active, and alive. You might imagine these black and white images as outtakes from

an MGM production of the movie of Pollock's life, as the lyrics of the soundtrack sing out "painting with spirit and heart."

Our films are short documentary pieces, natural in their production style, and hopefully clear that the artist is the focus

of the film, not the interviewer, Matt Bertles, my business partner, nor any other commentator such as a critic or historian.

I didn't anticipate the many different ways in which each artist interprets how such films will be made or used. For the most

part, we have been successful at persuading artists to be filmed; some, however, don't want to be filmed working or in their

studio because their work is neither painting nor sculpture and relies heavily on research or computer work or just writing.

So, we look for solutions that will work for the artist and for us. In the end, I hope that the films will recognize the nature

and spirit of art making and give the viewer a clear perception and understanding of what it is to be an artist and to make

art.

In the films, we see the artists at work in their studios. Are we really seeing them at work

or are they performing for the camera? Why is it important to create a portrait of “the artist at work”?

No, in the films the people are not pretending to work. This is important to understand--and I hadn't thought it would be

considered a "set up" shot. The working is part of the dialogue, part of an introduction, if you will, to what the artist

does, who he or she is, and how what they do and what they say come together. Because I imagine the audience for these films

extends beyond the confines of the art world I think that there is a profound curiosity as to what goes on in the studio;

how works are made; what decisions are part of the process; how does a work start and also when is it complete?

In the end, it is important to document artists because, for the most part, unless they have achieved prices of astonishing

note or have created a significantly controversial work, the life and work of most artists, architects, designers, photographers,

etc. goes unrecorded. Although we have traditional monographs and catalogues, there is nothing on video. To have such a library

in the future will be important to students of art, culture, and history. How artists worked, lived, thought, and expressed

themselves will always be of interest to future generations.

Imagine studying works of art in a lecture class and then later logging in to watch a film about that same artist: hear their

voice, see their studio, and listen to their ideas in real time.

In 2006, the Met hosted an exhibition of artists and works handled by the Parisian art dealer Ambroise Vollard. Surrounded

by Cezannes and Picassos, the crowds nevertheless collected in the gallery in which a short, three-minute silent film of Vollard

sitting with Auguste Renoir as he painted was showing. It was a crude, silent, three-minute film but it told us much: we all

wanted to know what they looked like; after all, they are people, like us, engaged with each other through art.

For more information, please visit www.talkingpointfilms.com and www.michaelkleinarts.com.

Deanna Sirlin is Editor-in-Chief of The Art Section and an artist whose work can

be seen at

www.deannasirlin.com

|

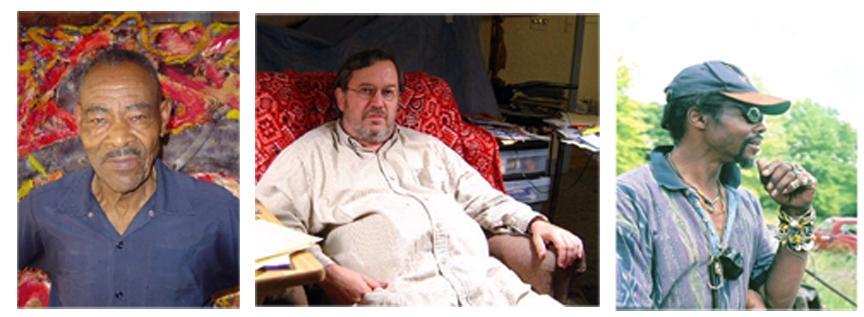

| Andrew Dietz, Photo: Joel Silverman |

Paradox Lost:

How I learned to stop worrying and embrace exploitation

by Andrew Dietz

Six years ago I was tempted by the forbidden fruit of paradox and ejected thereafter from the garden of art purity. It has

been six years since I began research on a narrative non-fiction book about exploits in the folk art world and now two years

since it entered bookstores nationally. The Last Folk Hero has been heralded by major national publications and vilified in folk art circles. It has been promoted at

many of the country’s leading museums and banned by several others. The story started as a simple chronicling of creative

spirit but morphed into a study of art world paradox. That is what art does best – unearth paradox – devilish

and unpleasant as it may be. So, why not write a book about it. Paradoxical thinking is what the powerful, rough hewn art

of Thornton Dial, Lonnie Holley and the Quilters of Gee’s Bend provokes. It is what the hyperbolic, whirlwind art patronage

of Bill Arnett inspires.

I first conceived The Last Folk Hero as a celebration of creative fervor and self-expression which conquers all adversity.

Just consider the life of Lonnie Holley – who was born to a woman who birthed twenty-seven children; was stolen from

her at two years of age; sold for a bottle of whiskey at four; and who spent the remainder of his childhood in an abusive

Alabama youth detention center for “negro juvenile law breakers.” Yet, by the time he was thirty, his art was

touring the world with the Smithsonian. Lonnie Holley is heroic creativity embodied. Thornton Dial too. Gee’s Bend Quilters

too.

As the layers of this story revealed themselves, they presented a series of Gordian Knots which choked the theme of heroic

creativity. The most thickly tangled knot pervaded the story and taints it still today. “What is exploitation and what

isn’t and who has the right to say?” If we say that wealthy white people who approach poor black artists and buy

their art for a pittance and sell it for a profit are exploiters we are saying, at the same time, that the artists are too

naïve to protect themselves. In addition to the fact that such a stance may be perceived as racist, it is also a way for us

to exploit the position of both collector and artist in order to publicly assert our own superior moral position. The Last

Folk Hero highlights this double bind and many readers are uncomfortable because of it. It has led to the refusal of several

major museums like the High Museum in Atlanta and the American Folk Art Museum in New York to offer the book in their museum

stores. It is likely behind the suggestion of Bill Arnett’s publicist that the book should be burned in a bonfire. It

is partly the inspiration behind the art work of folk artist, Big Chief, who created a work of art using The Last Folk Hero

as his theme. Big Chief nailed the book to a tin-covered hunk of wood and slammed a red ax through the four hundred pages.

Alas, responses of avoidance and aversion aren’t the way to resolve any paradox. They only tighten the knot.

Creation and exploitation co-arise. Perhaps beginning with the Palaeolithic painter who marked cave walls in Lascaux, creators

and patrons have complained about each other, lusted for each other and battled for power, recognition and currency. There

is no art for art’s sake. Art is always created with an intended impact. Even if the initial intention is simply the

artist’s self-impact. Eventually, it seems, that is never enough. Others must see, approve, and pay. Patrons fund continued

creation so that they may bathe in art’s presumed authenticity. Money needs art and art needs money.

Authenticity is difficult to prove. Which art is truly pure and untainted these days? “Folk art” is a term, for

instance, that connotes authenticity, purity, and insulation from poisonous popular culture. Where does this exist? A folk

artist can live in the middle of nowhere and still suck down hundreds of channels with a satellite dish affixed to his authentic

shack. Consider the three Gee’s Bend quilters who are suing the collector Bill Arnett for their presumed fair share

of his presumed windfall from selling their creations and related imagery. Should the litigious quilters be considered authentic

craftspeople or commercialists? Is Arnett an authentically pure patron who selflessly enriched the lives of these quilters

or an authentically shrewd businessman who profited at their expense? What if the answer to all of these questions is “yes?”

What if it is “no?” What if it is “well … yes and no?” Does any of it matter to the art? Regardless,

as the warring parties strive for what will likely be a closed-mouth settlement of the cases, we are unlikely to know what

a court might decide and so we are left again with vagaries and paradox.

It is equally difficult to identify most forms of artist exploitation. I was confused about what was or wasn't exploitation

in The Last Folk Hero when I first approached the story in 2002. I worried that there was something more black and

white in the situation that I was missing or ignoring or minimizing. So, I decided to ask the one person I knew of who studied

exploitation for a living: Professor Alan Wertheimer of the University of Vermont wrote the 1996 book appropriately titled,

Exploitation (published by Princeton Universtiy Press). Here's what he had to say about the subject of exploitation

in relation to the characters and events chronicled in The Last Folk Hero:

Mr. Dietz: I have finally had a chance to read your book. It turns out that I did

see the exhibit of the Gee's Bend Quilts at the Whitney a few years ago. It’s a very interesting and complex story.

I was a bit perplexed by what 60 Minutes thought it was doing. I don't know how much light I can shed on the issue of exploitation.

As you know, my approach is philosophical and somewhat technical. I am at pains to distinguish between what I call harmful

and non-consensual exploitation as opposed to mutually advantageous and consensual exploitation. And it does seem to me that

whatever exploitation there might be falls into the latter camp. Were the artists treated fairly? That's a complicated question.

Suppose that X has a Picasso in her attic and doesn't know what it is and is about to throw it away. I realize that it's a

Picasso and offer her $1,000 for it. She's better off than she would have been, but it's arguable that I took unfair advantage

of her ignorance and gave her much less than a fair price (which could be less than the market price). Your cases are even

more complicated than that because there was no market in this art and, moreover, Arnett was arguably instrumental in creating

the market for it. I should tell you that the chapter of my book (Chapter 7) in which I try to develop an account of fair

transactions is the least successful chapter in the book. I believe that some mutually advantageous transactions are unfair,

but it's very difficult to specify a principle that allows us to make that judgment and I do not think that (as Potter Stewart

said about pornography) that we know it when we see it. I think people may think something is unfair when it's not and think

that it's fair when it's unfair. Thanks for sending the book along. Best, Alan Wertheimer, Department of Political Science,

University of Vermont

In short, who knows?

The producers of 60 Minutes, that’s who. They’ve exploited the issue of alleged artist exploitation for

years. Morley Safer’s piece “Tin Man” attempted to put a spotlight on the subject, skewering on the same

stick Bill Arnett and the artists he championed. Unspoken in the 60 Minutes piece were the other nasty and false whispers

that floated around at the time. These hushed voices raised doubt about the authenticity of artwork championed by Mr. Arnett

– insinuating that he strongly influenced the material created by his folk art savants. While such was not the case,

nonetheless the damage of doubt was done. The Tin Man episode, its origins and aftermath are primary elements in The Last

Folk Hero which was released in 2006. Coincidentally, in 2007 film director Amir Bar-Lev released his documentary, My

Kid Could Paint That, a symbol that this artist exploitation paradox folds back on itself endlessly. Bar-Lev explores

the life of Marla Olmstead who rose to art world fame when she began painting abstract canvases at age 4 and her parents began

selling them for big money in major art galleries. In the midst of filming, 60 Minutes launched an episode simply titled

“Marla” which aimed to prove that Marla’s father – an abstract painter – was “helping”

his daughter create the work. While this was never proved conclusively, again, the damage to artist and patron was done.

It was while contemplating this mental muck around artist exploitation that I happened to speak with my friend, conceptual

artist Jonathon Keats who arrived at a – we thought at the time - clear answer to both the artist exploitation and authenticity

quagmires. After reading The Last Folk Hero, Keats concluded that the solution to the puzzle was botanical. “Folk artists

have caught on to their folksiness,” he told me, “so that in essence they are imitating themselves. I see it as

the same media-saturated self-consciousness that's debilitating contemporary art across the board." Except within the plant

world he concluded. "Plants are non-sentient. A sapling isn't making art to be a Robert Rauschenberg, let alone a Grandma

Moses." Keats told me that he intended to begin art farming and he asked me if I'd consider acting as exclusive dealer. After

writing The Last Folk Hero, I knew the market as well as anyone. I thought, 'Why the heck not?'" After all, it must

be easier to exploit non-sentient beings than sentient ones. They are less likely to sue. 60 Minutes is less likely

to care.

Following additional research, Keats and I determined that Georgia's seven million acres of tree farmland would provide an

adequate agricultural base, and that young Leland Cypress trees, limber and resilient, were especially well suited to high-output

artistic production. So we convinced the Kinsey Family Farm in Forsyth County, Georgia to grant permission to work with their

crop – usually reserved for Christmas tree buyers. We selected fifty exemplary saplings, and, for nearly three days,

we provided them with a variety of drawing implements as well as individual easels, to produce original works on paper. The

finest examples were culled and exhibited by Agrifolk Art Associates, my newly-formed dealership, at a gallery in Atlanta.

A documentary about the project, by critically acclaimed Atlanta film studio Eyekiss and director David Edmond Moore, was

created about the effort and is available on YouTube.

Trying to solve the riddle of exploitation in the art world is like cracking a Zen master's koan...it is a paradox wrapped

in a Gordian knot that even the experts can't fully untangle. But, like working through any good koan or paradox, simply noodling

the "E" issue can help to dissolve it or, at least, may increase the likelihood that we will act with greater awareness and

care going forward. Usually, resolving a koan is accomplished not by fighting it but by embracing it and embodying it or releasing

it like a helium balloon in a gust of wind. Maybe the truth is that none of us can get through a day without exploiting someone

or something. Therefore, like a good Agrifolk artist, maybe we should just get over ourselves and embrace this basic instinct?

|

| From left: Thornton Dial, Bill Arnett (photos A. Dietz) Lonnie Holley (photo L. Bunnen) |

To hear the author read the following excerpt from The Last Folk Hero: A True Story of

Race and Art, Power and Profit (Ellis Lane Press, 2006), please click here.

A July sun torched the asphalt streets of Pipe Shop as Bill Arnett and

Lonnie Holley drove slowly searching for Thornton Dial's modest home. They

were a modern-day Sancho Panza and Don Quixote. "This it over here," Holley

said, gesturing toward a one-story red brick house. When they got out of the

car, Holley coddled a small expressionist sculpture (a fishing lure made by

Dial which was more art than lure), careful not to let the protruding hooks

cut his flesh.

Dial was wary of the odd couple as they approached his door: the radical

black man with dreads and the pasty white man. Not long before, a friend had

warned Dial that he needed a license to make the "things" he was crafting.

Dial was sure now that the white stranger at his door must be a city

license-man.

"Mr. Dial, please open up. We would like to see your art, Mr. Dial," Arnett

coaxed, holding up the fishing lure. "Do you do anything besides these? Have

you made anything else? Any other art?"

"No, man," said Dial behind the door. "I don't know what you talking about."

Arnett tried asking again, phrased it differently. Same response.

"Show him what you do, Lonnie," Arnett suggested.

Holley quickly gathered a soda can, twigs, string, and wire from the yard

around him and conjured up a sculpture.

"Oh, you mean that kind of thing?" Dial said as the door eased open. "Yeah,

man, I done some of that."

In fact, since the flood that destroyed years' worth of his work, Dial had

continued to create "things" obsessively-not just useful, marketable objects

but also things that gave him personal pleasure just in the creation. Many

mirrored the world he saw around him-a harsh, unforgiving place-but he

didn't imagine anyone would ever care about them. After Clara Mae had told

him to "get that shit out of the house," Dial had stashed his art in the

turkey coop out back, his junkhouse. What didn't fit in the junkhouse, Dial

buried in the dirt.

Thornton Dial disappeared into the junkhouse and reemerged with an

eight-foot scrap-metal bird, a turkey tower mounted with an abstract

gobbler. Arnett and Holley looked at each other like gamblers facing a

machine that blinked "Jackpot!"

"Would you be willing to sell that, Mr. Dial?" Arnett asked. "How much would

you take for that piece?"

"What? You must be crazy," Dial said, but thought he was beginning to like

this white man. "I don't know, man, give me twenty-five dollars for it," he

continued.

At that moment something stirred inside of Thornton Dial, something that he

hadn't experienced in a long time. He thought it might be excitement. "Well,

you give me a price on it then if you think you taking it," Dial countered.

"Will two hundred dollars do?" Arnett offered. "Do you make anything else I

can see?"

"What?" Dial said. "Ooh, yes, man, I can make anything. Man, you crazy. You

got to be crazy."

By then, Dial's sons had gathered around the negotiation. They were

laughing. Saying, "You paying him for that? Man I'm gone tell you, my daddy

gone make a whole lot of stuff for you now."

Andrew Dietz is a writer, entrepreneur, and art lover based in Atlanta, Georgia. Please visit www.thelastfolkhero.com

|

| Photos by Donn Young and Frank Aymami. Courtesy of Creative Time. © All rights reserved |

Creative Time's Waiting for Godot:

An Interview with Curatorial Assistant Shane Brennan

by Laura Hunt

In November 2007, Creative Time, Inc., a non-profit organization based

in New York, produced five free outdoor performances of Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot in the Lower 9th Ward

and Gentilly neighborhoods of New Orleans, LA. Originating with artist Paul Chan’s creative vision, the project, which

included the play, a shadow fund, and an experimental film by

Cauleen Smith, was co-produced by Curator Nato Thompson and The Classical Theatre of Harlem. Christopher McElroen, co-founder

of The Classical Theatre of Harlem’s, directed, and the production featured New Orleans born actors Wendell Pierce

and J Kyle Manzay.

I recently spoke with Creative Time’s Curatorial Assistant Shane Brennan about his experience working on the project.

How did you react when you saw first-hand the devastated neighborhoods of New Orleans?

The media coverage of Katrina and its aftermath was saturating. Coming to New Orleans for the first time after the hurricane

was, for me, strangely like stepping into the media images—except that the sounds and smells and visuals were so much

more striking; once we drove into the Lower Ninth, the land was flat—tall grass, deserted roads, cement foundations,

and the occasional FEMA trailer in the distance. It was post-apocalyptic and eerily still. It goes without saying that it’s

just terrifying to see how little has happened since 2005. The brand new levee in the distance felt more like a constant reminder

of the past rather than a hopeful gesture towards rebuilding.

The landscape felt photographic in another way, in that it felt like time had stood still for the last three years. I think

this stillness was an inspiration for Paul when he imagined “Godot” being staged on this readymade set.

Even though the immediate surroundings were desolate, they weren’t devoid of activity. When we got there, Common Ground

was hard at work and, disturbingly, “disaster tours”—white busses with tinted windows—would occasionally

drive though. In a matter of hours, too, we had trucks delivering the risers and lighting gear that would define the intersection

of North Prieur and Reynes as a stage. And the activity just kept building throughout the week until thousands were lining

up to see the play, demanding an added show after its two-night run in the Lower Ninth.

What are some bits of memorable conversations you had with local residents?

I remember setting up the makeshift front-of-house for the show, basically a bunch of folding tables and chairs set up on

the cement slab where a house used to stand, a few blocks away from the “stage” in the intersection. Here, the

playgoers would be served gumbo by the glow of a half-dozen strands of white Christmas lights before a second-line parade

would march them to the site of the play. We were moving some portable toilets into place in the grass across the street when

a pickup truck slowed to a stop nearby. The family driving told us that the place we were setting up the tables used to be

their home, before it was literally washed away.

They had read about the production in the Times-Picayune and had driven from Houston to see it. I remember feeling

like an intruder, preparing to heat up vats of gumbo in what used to be their living room. We were a bunch of art producers

from New York using their former neighborhood to stage a play—it all seemed absurd at that moment. But they surprised

me by thanking us. Thanking us for bringing people back to the Lower Ninth. For turning the lights back on. For making people

pay attention again. And for bringing some much-needed celebration and entertainment to a patch of land and a city of people

that have seen so much ruin.

It’s strange, but many of the conversations didn’t sink in until I left and had time to reflect. In all the chaos,

it was hard to process what was going on—how Beckett’s seemingly meaningless words were charged with the landscape

around us. When lines like “This is a forgotten place” were spoken, people were brought to tears.

I would imagine that the following exchange between Estragon and Vladimir was particularly

painful to hear:

ESTRAGON:

All the dead voices.

VLADIMIR:

They make a noise like wings.

ESTRAGON:

Like leaves.

VLADIMIR:

They all speak at once.

Definitely. One of the most memorable stories I heard was from a family that drove down from Tennessee to see the play staged

on their old stomping grounds—certainly the longest pilgrimage we heard about. The father of the family, Randy McClain,

a New Orleans native, wrote a letter that was printed in the Picayune that came out as the play opened. For me, no other words

better encapsulated the mission and success of the project. So, here it is:

Friday morning at 7 a.m., my 14 year-old son, wife, and mother will start the roughly 560-mile drive from Nashville,

Tenn., to the corer of North Prieur and Reynes streets to see a corner lot staging of Waiting for Godot.

The only Katrina refugee among us is my 80-year-old mother, wiped out in St. Bernard Parish in 2005. She lives in Middle Tennessee

with my family now. The rest of us moved from Louisiana in 2003—before Katrina. But our drive to see Godot has

more to do with my son, Markus, a young actor and a freshman at the Nashville School of the Arts here.

I want him to see how a neutral stage can become a place of social and political comment and a play can be a call to action.

I want my son to see theater that touches lives and does more than just entertain. So, we’re driving for nine hours,

lawn chairs in the trunk, to see art.

It still gives me chills.

Could you describe the stage props created by Paul Chan. Did he use found debris from the

storm to create them?

I know there was an old, moldy refrigerator door involved.

Of course the centerpiece of the play is the sad runt of a tree that stands center stage. His design was very minimal, but

very evocative. As the artistic director, I don’t think Paul wanted the props—like the ramshackle grocery cart

covered with clusters of plastic bags—to draw too much attention. The real set was the grass, cement, trees, and debris—and

really the moist air, the impenetrable darkness, the sounds of insects, the smell of bug spray, and the energy of 600 people

in rapt attention—that was all around us.

There has been much response to Waiting for Godot in New Orleans from the press, the

art world, and New Orleans residents. Have you heard anything from the government, public officials, or political figures?

I heard that the mayor expressed interest in creating a Waiting for Godot Day, to commemorate the November production.

He was supposed to attend one of the Gentilly shows, and wanted to deliver a speech before the play started. When he was told

that we weren’t allowing any speeches, this must have been a turn-off because he never showed. What’s great is

that the press coverage and local word-of-mouth was so strong that there’s no way that any official could have avoided

hearing about it.

Beckett's play famously deals with the existential crisis of humanity, and producing it in

post-Katrina New Orleans frames this tragedy in a real and current setting. Beckett is absurdist; blame is irrelevant in

his world. But when examining the reaction to Katrina, it’s natural, inevitable even, to resort to blame directed at

the U.S. government. Could you reflect on this? Where can one draw the line between unavoidable human tragedy and a tragedy

that has at its root some element of fault?

There are a lot of questions like this that remain in suspension, unanswered (nor attempted to be directly answered) by Paul’s

project. As much as the play felt startlingly—almost terrifyingly—at home in the Lower Ninth, I hesitate to give

too much weight to the parallels between the play and post-Katrina situation. One can clearly see the connection between the

play’s absurdity and, say, the absurd and terrible response of the government—how FEMA decided its own trailers,

which were designed for temporary use and still had people living in them three years out, were too dangerous for FEMA workers

to enter due to poisonous formaldehyde levels. Or, in a different way, the absurdity of seeing hundreds of white people, a

good amount of them affluent out-of-towners, coming to see a play in the Lower Ninth, only after it was leveled by a hurricane.

For me, the point isn’t to read the post-Katrina political situation through the lens of Beckett’s tragicomedy;

but rather, to see how his words—most of which are empty, absurd, or full of nothingness—seep into their surroundings,

shedding light on everything that’s happening, or should be happening, or should have never been allowed to happen.

Maybe their ambiguity allows this to happen more readily. The inaction in the play, all of the “idle discourse”

and nonsensical banter, turns up the contrast on everything around it until you see the New Orleans you’re immersed

in in stark relief.

The attempt to determine fault, or uncover the reason behind the situation, starts to feel just as absurd as Beckett’s

characters irrational patience as they await Godot, who, of course, never arrives. As much as the play is a story of waiting,

a story in which “nothing” happens, it sheds light on the people in New Orleans who have refused to keep waiting

for help that may never come, and who have taken action, rebuilt, and survived.

The real magic of the play was the energy it created and the mass of people it brought together. The content had a poetic

connection to the state of the city (and Godot has a history of being performed in radical contexts, like prisons),

but the exact words almost didn’t matter. Gathering together more than 600 people—all with different backgrounds

and different stories to tell—in one place to see a theatric production (a production that was itself a collaboration

of hundreds of people from New York and New Orleans) was extraordinary. Once everyone was seated in the risers and the stadium

lights went down on the intersection, even before the play started, I knew we had helped create something that would last.

For more information on Waiting for Godot in New Orleans, please visit www.creativetime.org/nola.

Laura Hunt is an artist and writer who lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

|

|

|