|

|

|

| Martin Vosswinkel, Color Mobiles in Berlin. |

Introduction

by Deanna Sirlin

Editor-in-Chief The Art Section

In this month’s TAS,our first anniversary issue, we have a mélange of perspectives. “A Letter from Berlin”

follows some of the recent thoughts and journeys of Michael Nentwich, former Director of the Goethe Institute in Atlanta,

who is now making his home back in Germany after 12 years in the United States. Martin Vosswinkel, who is from Bremen, Germany,

also talks about how travel transforms one’s perspective from the artist’s point of view by writing about his

recent studio time in Berlin. His writing has been graciously translated for us from German to English for us by artist Christina

Price Washington. Novelist Jennifer Cody Epstein has taken a fictional journey inspired by a Chinese painter whose work she

was moved by and about whom she wrote her first novel. Here, she writes about that journey and reads from The Painter from

Shanghai.

So, travel is our theme, certainly an appropriate one now that we think so often about what is happening globally.

And my salutation is a quote from an email from Martin Vosswinkel: “a hug, a night kiss, and a lot of Berlin air.”

All my best,

Deanna

|

| Photo: Sig Guthman |

www.deannasirlin.com

|

| Color Mobile by Martin Vosswinkel. |

"Color Mobiles" in Berlin

by Martin Vosswinkle

Originally published in Up Art: The Newspaper of the Bremen Federation of Artists, No. 25 (March 2008).

Translated from the German by Christina Price Washington.

I was told along the way that it would be better to arrive during the daytime since it would be difficult to find the studio,

which was located in the back of a courtyard, in the dark. Naturally, I arrive in the evening and it is dark. The directions

were so clear, however, that I found the studio within minutes. When I enter, I find myself in an empty space which is going

to be my base for the next three months. It is difficult to describe what all was going through my head when I first turned

on the light. Pure luck, perhaps? I like the room as empty as it is, as clear and minimal as many of my paintings. I would

prefer not to add anything to this room. Just to be in an empty room for three months. In this moment, I realize that I have

taken too many things from my studio at home. Not just materials but also ideas I wanted to turn into art. Now I meet this

room, and am suddenly in the middle of the artistic process. I take lots of time to unload. I document photographically every

change I make to the room with each thing I place in it. While I carry my especially huge aluminum sheets, I think that since

I will inevitably pack them back up, unworked, in three months I could just as well leave them in the car. Of course, the

painter in me wins and they stay in the studio.

After a couple of days of painting, the question arises of what sense it makes to move the studio 400 km to the east just

to do the same thing as always. I have to get out. The city is pulling me like a huge magnet. On my first scouting trip, the

backside of a billboard immediately catches my eye. It is empty, and the sky is reflecting in the metal background, so that

the surface seems to be transparent. I notice the red frame and think about “Gates,” a series of my paintings

whose monochromatic, empty centers also work with filigrees of color around their edges. The city defines a moment in me and

I decide in that moment to find my paintings in the city or bring them into the urban environment.

In the following days I walk in all directions through the city and obsessively photograph billboards. I am not at all interested

in their content but, rather, in the spacial situations in which they appear and what they contribute to the composition of

the environment. I am especially fond of those that are lit at night. They seem unreal, like oversized bedside lamps which

throw their reflecting colored light onto the street and suggest an intimate atmosphere.

Back at the studio, the commercial content of the billboards is removed and replaced with a brilliant surface of color. I

also get in touch with advertising agencies to see if it would be possible to place my designs in certain spots. But they

need more lead time, which means it would only be possible to place this kind of work in the urban space at a later point

in 2008.

After the first round of photos in the early morning, I warm up in a bistro. Between coffee, croissants, pilsner, and sausage,

Berliners engage in their daily discussion of politics. Everybody finds something to complain about. A retiree places his

cup of coffee on the bar and adds to a heated conversation, “I’ve been told that the Eskimos aren’t happy

with their government, either.” I find myself thinking, “There’s the dry Berlin humor I love.”

As I photograph subway and street car stations, security guards ask me to stop. I need permission. The next day, I speak to

somebody on the phone who seems to be in charge and who informs me that this is absolute nonsense. He sees it as an act of

art documentation or souvenir photography, and either is allowed. He gives me his cellphone number in case of an emergency.

The following evening, I take pictures for several hours at the Gesundbrunnen train station when a guy with a bitter face

and aggressive tone of voice approaches me and asks what I am taking pictures of. I start to say that I have permission, but

I end up saying that I am an artist. His face relaxes and produces a smile. Oh, an artist, he says, as he walks away, his

sister’s boyfriend is also an artist. To be an artist in Berlin seems to be a type of hall pass, since everybody knows

somebody who is an artist.

Meanwhile, I’m asking myself just what I am doing in Berlin, and my still unworked aluminum panels seem to ask me the

same thing. Cornelia Wichtendahl, my gallerist, encourages me to pursue the projects I have started.

In December, I start touring my “color mobiles” through the area called Wedding. I began this project in the

summer during the gallery days in Berlin: colorful squares are placed onto everyday vehicles like a wheelbarrow or a shopping

cart. They are pushed through the city and photographed to explore different spacial situations. For brief periods of time,

the “color mobile” forms an installation or an urban color field that disolves only to reform anew a few meters

away - the movement of a specific painting in space. A few streets in Wedding seem to be abandoned. Even so, because many

window shutters are closed, offering quietly colored surfaces, a clear composition emerges.

On Sunday, I make my way towards the Bundestag with another color mobile. I try to photograph it in front of a big concrete

wall opposite of the Bundestag, but the wind is so strong that it keeps knocking it over just before I take the picture.

There are surveillance cameras everywhere. I wonder what the guards must think when they see me on their monitors, but nobody

comes and asks me what I am doing. On the fifth try, I succeed. But when I leave, a bus with tinted windows follows me at

a walking pace. When I sit on a bench, they stop. After a few minutes, they lose interest and move on.

Of course, I saw a lot of exhibitions, visited museums, and went to openings. The Brice Marden retrospective at the Hamburger

Bahnhof was excellent, but I had seen it in the fall.

Jannis Kounellis’s “Labyrinth” at the Neue Gallerie and, of course, Jeff Wall at the German Guggenheim -

especially his light boxes. Perhaps the one that stayed with me the most was Karin Sander’s exhibition at Studio Sassa

Truelzsch, a small project-room with only one piece made out of white chocolate that looked like a small monochromatic painting

on linen. Also worth seeing is the popular new gallery quarter on Heidenstrasse across from the central train station, where

large and small galleries and artist’s studios disport themselves.

It was worth visiting the Galleriehaus on Lindenstrasse and seeing a group exhibition at Krammig H Pepper on my last evening.

After the opening, we visited a little bar with Nicholas Bodden, Barbara Rosengarth, the gallerists and their artists—a

fitting finale for my time in Berlin.

As I carry the big unfinished aluminium sheets back to my car, I think that it was good to follow the momentum of the city.

Berlin has changed the way I view things. I would like to come back.

Martin Vosswinkel is an artist who lives and works in Bremen, Germany.

www.martinvosswinkel.de

| Works from the Female Impressionists Exhibition |

|

| From Left to Right: Works by Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morisot, Eva Gonzalez, and Marie Braquemond. |

Letter from Berlin

by Michael Nentwich

I

I will never forget my first coast-to-coast trip across the United States. I was no longer a student and was earning a decent

income, but I was afraid of overspending and did what I would have done in Europe: I used buses and trains and avoided renting

cars, assuming they were too expensive.

I arrived in Albuquerque, NM, bought a map, looked for the city center, and started walking. After an hour I had still not

arrived anywhere near a downtown area. But a car stopped, and the driver told me that he had been in Germany as a GI and he

thought I could only be a German walking in a strange area like this. When I asked him where downtown was, he pointed behind,

and he kindly turned around and drove me there. I had missed it because, for a European, American cities (with few exceptions

like New York, San Francisco, and New Orleans) don’t really have centers; they have skyscrapers instead. They are, as

the quip has it, suburbs in search of a city. For a European, a city is a place where buildings, usually old, stand very close

together and people walk in narrow streets and buy food in open air markets. Oh yes, we have cars, too. But in town, we use

public transport, because it is faster and there is nowhere to park.

When I moved to the US, I learned quickly enough that American cities have more or less everything European cities have. But

you have to drive there. You can’t study other people in the street, because you drive past them. You have to go somewhere

specific to observe them, like a shopping mall. Some of these I found spectacular, but I still missed the sensation of standing

in a square and looking at Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque buildings around me and imagining that hundreds of

years before, people had already walked and looked at each other there. Americans must share these feelings: they would not

have invented Disneyland had they not felt a yearning for those old city centers that are a part of their heritage, too, but

were not accessible unless one traveled across an ocean.

I’m certain that Americans have problems stemming from cultural conditioning as well when they travel to the Old World.

But surely the American social studies teacher who recently told me that she visited Rome but was disappointed because it

was so shabby and full of ruins was not representative!

II

So I would expect American art lovers to come to Europe to see old things. Moving to Berlin after twelve years in the US,

however, I was surprised to note that visitors come to Berlin because of its reputation of being cutting edge. And it is.

When the European Union was founded, France was the center of it, and (West) Germany was at the edge, along the Iron Curtain,

behind which, for all intents and purposes, was nothing. But with the fall of the Wall in 1989, all that changed. Suddenly,

the EU includes Poland and the Baltic and some Balkan countries, and reunited Germany is in the middle of it. Especially Berlin,

which is now Europe’s number three tourist destination after London and Paris. New York artists are moving to Berlin

in droves, because the city is full of creativity and prices are more modest than even in Brooklyn, let alone Manhattan. Even

international artist stars like Olafur Eliasson and Mona Hatoum have their studios here. Commercial galleries have been growing

like mushrooms in the rain. The Berlin Biennale for Contemporary Art, the fifth installment of which is currently taking place,

is fast becoming Germany’s answer to the Whitney Biennial in New York. The Art Forum has overtaken Art Cologne to become

Germany’s number one art fair. Perhaps the most exciting shift is the fact that many Western German collectors are moving,

or at least moving their art, to Berlin. The wonderful state art collections on Museum Island and at the Kulturforum are being

augmented by a growing number of private museums, the most impressive one surely the Boros Collection, installed in a World

War II bunker which the East German authorities never dared take down because the explosion might have destroyed the surrounding

buildings. Christian Boros himself, who made his fortune with an advertising agency which counts Coca Cola among its customers,

has moved from Wuppertal to Berlin and occupies a splendid penthouse on top of his bunker.

Not everybody is happy. The State Museums are criticized for ignoring the artistic activity in their city in their acquisition

and exhibition policies. But as for art production, and as a destination for the traveler interested in contemporary art,

Berlin is now with London the top destination in Europe.

III

Come to Berlin by all means to see the new. But while you are here, don’t forget that you are still in the Old World.

Even if your passion is contemporary art, don’t forget that the good artists usually know the old masters and have learned

from them. While Berlin does not rival New York or Washington as a venue for blockbuster exhibitions, there are always important

shows on around Germany and in neighboring countries.

If two or more are traveling together, you may find that renting a car can be less costly than taking trains (rental cars

are now a lot cheaper than in my youth!). Locally, public transport or walking will get you everywhere you want to go, but

if you want to travel around Germany, a rental car is an option. Trains, especially the ICE, are fast and elegant, but expensive.

And while Germany has more than eighty million inhabitants, the country is the size of Montana and it is easy to get around

in.

IV

America’s favorite historical art movement is Impressionism. American museums have the most wonderful collections of

Impressionist paintings outside of Paris. The Impressionist collections in German museums are relatively poor, because when

this art was being created, nationalism was rampant in Europe, and Germany and France were archenemies. The director of the

National Gallery, one of the five museums that make up the Museum Island complex, was Hugo von Tschudi. He appreciated Impressionism

and collected it. He even bought the very first picture by Cezanne for a museum. But Kaiser Wilhelm II, who was interested

in art but had an extremely reactionary and Germanocentric taste, made life so difficult for Tschudi that he eventually gave

up his Berlin post.

Contemporary Germans adore Impressionism as much as Americans do, so at least we get regular temporary exhibitions. One is

on in Cologne until late June. On display are 130 pictures by Manet, Monet, Caillebotte, Pissarro, Renoir, Gauguin, van Gogh

and others. The exhibition travels to Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, Italy where it will be from July until September.

More interesting because it is dedicated to a less frequently explored area is the Frankfurt exhibition on female Impressionists,

showing 160 works by Berthe Morisot, Mary Cassatt, Eva Gonzalez, and Marie Braquemond. Morisot’s paintings are gorgeous

in a Manet kind of way, with energetic brushstrokes that make colors dance before your eyes. The more sober Mary Cassatt is

closer in style to Degas, but the frequency of the mother-and-child theme in her work and the way she alternates between smooth,

“realistic” areas of painting and parts where the brushstrokes are clearly visible and create a pointillist effect,

amount to a style totally unlike that of any other painter. The numerous paintings by Cassatt in the show are a joy to compare.

They are more varied than one expects and make you realize and regret that so many of her works in major American museum collections

are not regularly displayed. If Eva Gonzales doesn’t make quite such an impact, it may be because of the selection of

the works. To judge by this show, Gonzales was a searcher who see-sawed between “traditional” academic studies

and extremely loose oil sketches. But in between, there are also jewels like the “Awaking Girl” from the Bremen

Kunsthalle, or the “Loge in the Theatre des Italiens” from the Musée d’Orsay in Paris.

Braquemond simply does not seem to be in the same league as the other three ladies, and the catalogue gives a reason for this.

Her husband, who was also a painter, but conservative and second rate, incessantly criticized her for her attraction to Impressionism.

He finally discouraged her so severely that she gave up painting altogether.

“Female Impressionists” is that ideal show, a blockbuster which at the same time gives us new insights into art

history. The female Impressionists represent an important stage in the emancipation of women artists, which depend on equal

opportunity in training and encouragement.

V

Have you ever stood before a masterpiece in a museum and dreamt of being very rich and able to buy it and take it home? If

you do, you will enjoy taking part in an auction at Sotheby’s or Christie’s. The most expensive Impressionist

and modern paintings are usually sold in New York, but for Old Masters, London remains the preferred venue. And if you want

to imagine being richer still, you go to TEFAF (The European Fine Art Fair), which brings a large temporary museum together

once a year in Maastricht, a Dutch town in the “Three Countries Corner” on the border with Belgium and Germany.

This year, it took place from March 7 to16, and it was more sumptuous than ever. Just watching the well dressed, more than

well-to-do crowds walk through the aisles or eat lobster (much more expensive in Europe than in the States!) and caviar in

the elegant restaurants was enough to make you envious. The first weekend alone, 160 private planes landed at the small local

airport. Many of the hotels raised their prices by 100% and were nevertheless fully booked. And the booths! Almost four hundred

of the world’s top art dealers were there showing antiques and works of art, paintings, drawings and prints, modern

art, classical antiquities and Egyptian works of art.

Inevitably, one overhears an Arab gentlemen from the Persian Gulf buying a Fragonard, just like that, say: “Now what

is your best price again? Can I pay by credit card?” How I would have loved to take Jan Steen’s “Sacrifice

of Iphigenia”, van Gogh’s “Child with an Orange” and literally hundreds of other masterpieces home

with me to my own private Persian Gulf! Or how about becoming an art dealer and striking it rich that way? One of the dealers

I interviewed, Mark Weiss, told me that he inherited a small antiques store from his parents in provincial England and made

it into the world class Weiss Gallery in London just by having a good eye. He never studied art history formally, but he once

discovered a painting by the Flemish painter Pieter Pourbus in a garage sale and has since become one of THE authorities on

the Pourbus dynasty of painters. How I would love to be Mark Weiss!

Exhibitions discussed:

5th Berlin-Biennale für zeitgenoessische Kunst, Berlin (Neue Nationalgalerie, Kunst-Werke, and Skulpturenpark Berlin-Zentrum)

until June 15. Tue-Sun 12:00am-7:00pm, Thu -9:00 pm

Kunstbunker Berlin (Boros Collection) by appointment: www.sammlung-boros.de

Impressionism – How Light was Brought to Canvas, Cologne (Wallraf-Richartz-Museum) until June 22. Tue-Fri 10:00am-6:00pm,

Thu -10:00pm, Sat-Sun 11:00am-6:00pm. Moves to Florence, Italy (Palazzo Strozzi) July 11-September 28.

Female Impressionists, Frankfurt/Main (Schirn-Kunsthalle) until June 1. Tue-Sun 10:00am-7:00pm, Wed & Thu -10:00pm.

Moves to San Francisco Fine Arts Museum from June 21 to September 21.

Dr. Michael Nentwich was director of the Goethe-Institut Atlanta from 2000-2006. He now lives in Berlin.

On Painting Pan Yuliang

(Or: On Not Writing What You Know)

by Jennifer

Cody Epstein

It’s safe to say that while I always knew I’d write a novel, I never dreamed I would write The Painter from

Shanghai.

Growing up, reading obsessively from Woolf and Wolfe, H. James and James J., I’d always imagined patterning my own first

book along the same lines. I saw it—quite modestly—as another seminal, semi-biographical coming-of-age story;

something that would draw from my own vivid if somewhat mundane experiences as a glum teen in Wellesley, MA, magically morphing

them into a luminous work of great wisdom and beauty. If anyone had told me that my debut work would draw from not my own

life, but one infinitely more distant; one not only largely undocumented (at least, not in words) but also set in a land across

the globe, a half-century before my birth, amid struggles and turmoils and revolutions of art and culture and government that

would take me years of scholarship to even start to understand—well, I would have said one thing: “You’re

crazy.”

In fact, this is precisely what I did say when the idea of writing about Pan Yuliang was first suggested to me, at

the Guggeheim Museum, nearly ten years ago.

My husband Michael and I were viewing a show of modern Chinese art. When I saw my first Pan Yuliang painting it intrigued

me: lush and Cezanne-esque, it pictured (like, I’d learn, so many of Pan Yuliang’s pictures) the artist as a young

woman, sad and wistful against her Parisian windowscene. When I read the accompanying biography (prostitute-turned-concubine-turned-pioneering-modern-painter;

really?!) my jaw dropped.

“Look,” I exclaimed to Michael. “Look at this AMAZING woman.”

My husband—a filmmaker with a good eye for plot and image—took in Pan’s striking image, her stunning lifeline

and my rapt, breathless expression. Then he turned to me.

"This,” he announced, “is your first novel."

“You’re crazy,” I told him.

And at the time, I really thought that he was. It was true that I had a Master’s in international relations; that I’d

lived in Japan and China. But I knew nothing about Asian art, or even about art in general. And I’d only started seriously

writing fiction—albeit mostly semi-autobiographical, longish short stories that had little of the authorial pull I’d

hoped for (which, in retrospect, is not surprising; there’s only so much literary depth to be plumbed from a despondent

upbringing in an upper-middle-class suburb).

And yet what had seemed a startling proposal slowly took root. In following months I sought out pieces of Pan’s life

and work like the parts to some enormous puzzle—if one I could only dream of completing. In some ways, the more I learned

the more daunted I became—who was I, who could barely manage to master her own, dull story on paper, to take on that

of a wounded, talented, unimaginably brave Chinese painter? Plus, there was so little to go on—even in Chinese; there

was, I learned, little concretely known of Pan. Her only legacy was her art; some 4000 odd paintings and sculptures that were—sadly

for me—mostly locked away in storage, in China. Even the dates on her Paris gravestone are debated. How, I wondered,

could I possibly weave a compelling, credible story from such sparse materials?

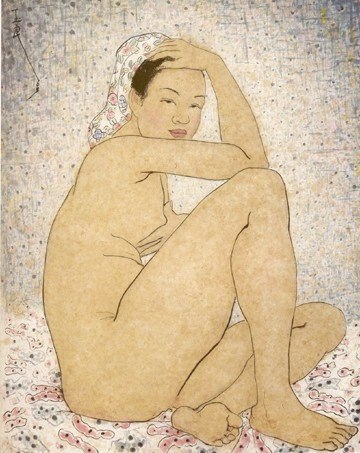

I found both my answer and inspiration, in part, in Pan Yuliang’s own work: the gorgeous and defiantly Western images

(often nude, often herself nude) that had so shocked her countrymen in the last century. The images—whether lush

pears or lithely curved female bodies—spoke to unrepentant fascination with beauty; with female strength; with sexuality;

with the often-fuzzy lines that delineate culture, nationality, morality. Artistic voice. If her somber self-portraits (in

only one I’ve seen is she actually, openly smiling) gave me a clue to her temperament and harsh past, her vibrant palette

and fanciful blendings of post-Impressionism and guohua, of Eastern discipline and Western romance and perspective,

gave me insight into her dreams, longings, her unique artistic eye—or at least, so I liked to think. At any rate, in

many ways they were the strongest sources I had.

So in the end, I ended up working largely through those images; searching lines and hues and expressions for clues

into the life that Pan Yuliang might have lived when she painted them. It was, as I imagined it, a life of beauty, pain and

drama; of more than a hint of real darkness. Of a lush love of form and color. Oddly enough, though, as I pieced together

this portrait I also—in the process—painted my own, after all. It wasn’t a Woolf-esque meditation on shattered

homes and lost loves and painful lessons in the wake of adolescence. It was a larger story, equally important to me and immeasurably

more colorful; a story of an artist finding her way. Creating her work out of unlikely and—initially—vastly alien

materials. In Pan’s case, those materials were nude bodies and Western techniques and the boldly unrepentant tones of

the Fauvists. In mine, they were foreign countries (China) and subjects (art; prostitution) and a shaky determination that—at

very least—somehow—I would see this thing through to the last word.

And in the end, I suppose, we both succeeded. Despite a life that ended in poverty, illness and obscurity—and the virtual

exclusion of women from the current Asian art boom—Pan Yuliang is now experiencing a renaissance in China. The museum

in Anhui Province (to which she left all her work when she died) recently has restored many of her paintings, and has dozens

of them proudly on display.

As for me—well, Painter may not be a breakout bestseller. And I’m still just a girl who grew up in a rich

suburb. But my book is being greeted warmly by the press and most readers I hear from, which is gratifying. They find, as

do I, inspiration and wonder in Pan’s story and her work. Though they do ask why I chose this topic, instead of something

closer to home.

Hmmmm. How to tell that story….

|

| Nude by Pan Yuliang (1963). Collection: Anhui Provincial Museum, Hefei, China. |

To hear the author read the following excerpt from The Painter from Shanghai (published by W.W. Norton, 2008),

please click here.

Doodlings, she thinks of them. Her little worthless scribbles: tiny images of fruits, flowers, monkey faces

and occasional dragon, topped with Qian Ma’s head. These are figures that almost of their own impetus bud and unfurl

in the blank margins of Yuliang’s copybook these days. To her eye, the small pictures are as inexcusably inexpert as

was that first grief-stricken sketch of Jinling. More than once, appalled at how her pencil has mauled a plum, she’s

vowed to stop altogether. And yet the little pictures keep coming, in a process both addictive and mystifying. It’s

the same need that drove her to stay up through the early morning hours at the Hall, coaxing peonies and fresh-faced peaches

onto cloth with her needle. But there, she’s discovering, is something liberating about ink or lead. Unfettered by thread,

she can bring the whims of her thoughts—whispering trees, wilting flowers—to life quickly, if often ineptly. And

even when the images are inept the solution is refreshingly simple. She simply rips the page out and starts over.

As more and more of her study time is devoted to art she starts to worry as she hands Zanhua her “study” sheets:

it seems impossible to her that he won’t reprimand her for putting so little effort into them. To her astonishmenet,

though, he doesn’t even seem to notice that the characters she once spent hours on are now dashed off in half that time.

He continues to praise her brushwork and the delicacy of her execution. At least, until one afternoon when he is at home working

in his office.

Yuliang is lying on his bed upstairs with her writing things. Lulled into a dreamy daze by the rain-patter on the glass, she

is thinking about the old French priest from their outing; about the deft assurance with which those meaty hands captured

a flowers frail beauty. The same feeling she’d had then—a thrill, blended with longing—fills her, and almost

without thinking about it she pages past the day’s vocabulary in her copybook. Tongue between her lips, she makes soft

gray sweeps on the paper. She adds more detail a faint line there, a smudge here. A dark crease to show the dainty fold of

a leaf. The flower’s flaws—its unevenness; the unnatural cast of attempted shading—needle her. And yet she

keeps on trying.

On her fourth try she takes a different approach. Instead of drawing line by line, she tries to tap into that flashquick association

between image and meaning that is the key to her growing literacy. Orchid, she thinks. Orchid. And without letting

her mind go any further, she puts her lead tip once more to the paper’s surface. When she is done she shuts her eyes,

then opens them again.

To her thrilled surprise, what she has drawn is just that: an orchid. It’s still a bit crooked, a little chunky in the

stem and stamen. She’d do better if she had one right in front of her. And yet anyone—a schoolboy, a child not

yet capable of reading the word, even, looking at this picture, would know it for what it was. Flushed with victory, she’s

just turning a fresh page to try it again when Zanhua flings himself on the bed, almost on top of her. “Ah-ha! Caught

you!” he cries nuzzling her neck. “You didn’t hear me come up?” He pulls her, copybook and all, into

a rough embrace. “The old sons-of-turtles are crazy,” he shouts. “There’s no way in hell we’re

going to be able to check all small craft in the Harbor before they reach the docks!”

“No way, certainly,” she says, into the lime-sweet pomade of his hair, “if you don’t ever leave the

house.”

He pulls back slightly. “Ah. You do want me out.”

She laughs. “Of course I don’t.” Snaking her arm out from under his weight, she tries discreetly to drop

the book over the bed’s edge. But he catches her hand back.

“Not so quickly,” he says. “Let’s take a look at your work, little scholar.” And, still pinning

her beneath him, he parts the book’s pages. She feels her face flush as he looks at her, then back. “Did you

do this?”

She nods.

Zanhua rolls off of her. Bending over the book, he begins paging through it intently. She watches him take it in: the scrawled-off

characters, the little pictures that she’d thought good enough to keep. The not-so-bad lotus, and the one that looks

like a lion. And the one that looks somehow squashed. But it’s the good one he returns to, tracing the black lines with

white fingers, frowning at it as though it were a puzzle.

“I was having difficulty concentrating,” Yuliang mumbles. “The rain...”

He doesn’t answer. Oddly anxious, Yuliang chews a cuticle. When it stings, she looks down to see that she’s bitten

too hard again: blood wells.

“This is how you spend your days now?” he says.

“I mostly do them after I study.”

“Have you had lessons?”

She laughs. “When would I have had lessons?” Then, realizing he means at the Hall, she bites her lip. “No.

Never. I—I just like to try to draw things sometimes. I’m no good at all.”

He purses his lips. “Actually, you are. You’re very good.”

The compliment all but takes her breath away. “I’m no Shi Tao,” she manages finally. “You can surely

see that--”

“It’s interesting,” he goes on, ignoring the comment.

“What?”

“That you decided to do – this.” He points to where she’s tried to show depth with clumsy cross-hatch,

a technique she’d seen on the cover of a New Youth issue “None of the old masters would pay this much attention

to depth.”

“I know. It’s silly.”

“That’s not a criticism. Artists—modern artists--should paint the world as it is. Not just as some—some

empty exercise. In aesthetic.” Turning slightly, he waves at the scroll that has hung in the room since before he first

led her up to it. “How many versions of that picture hang on people’s walls, do you think?”

Jennifer Cody Epstein is a fiction writer who lives and works in New York City.

www.jennifercodyepstein.com

|

|

|