|

|

|

| Work by Glenn Goldberg. |

Introduction

by Deanna Sirlin

Editor-in-Chief The Art Section

I am pleased to present three features in this month’s TAS on artists who are working, thinking, and mixing it up in

their genre. The first is the bold move of The Atlanta Ballet to invite Big Boi, an internationally known hip-hop artist

from Atlanta, to perform with them. “Hip-hop is a defining element of our city,” says the ballet’s Artistic

Director John McFall. “It only makes sense that the two art forms would come together at some point.” Frankly,

I wish more artistic directors would think it is natural to work in such hybrid terms. Phil Auslander gives us his reading

of this performance, which peaked my interest as well as his, although for completely opposite reasons. Well, all the better,

I say.

Artist and writer Cinqué Hicks has always been interested in maps. Here is his interview with New York artist Nina Katchadorian

about a new psychological reading of place. And then there is the voice of New York painter Glenn Goldberg. If you read his

essay closely, you may imagine the questions he is answering. In fact, he was addressing questions I posed him. However, I

felt that Glenn’s voice is clearer without my queries. Glenn gives us a picture of what it is to be a working artist,

which has not really changed much since we were in graduate school together in late 70’s. I am happy to report we are

both still working at the job of being an artist.

All my best,

Deanna

www.deannasirlin.com

|

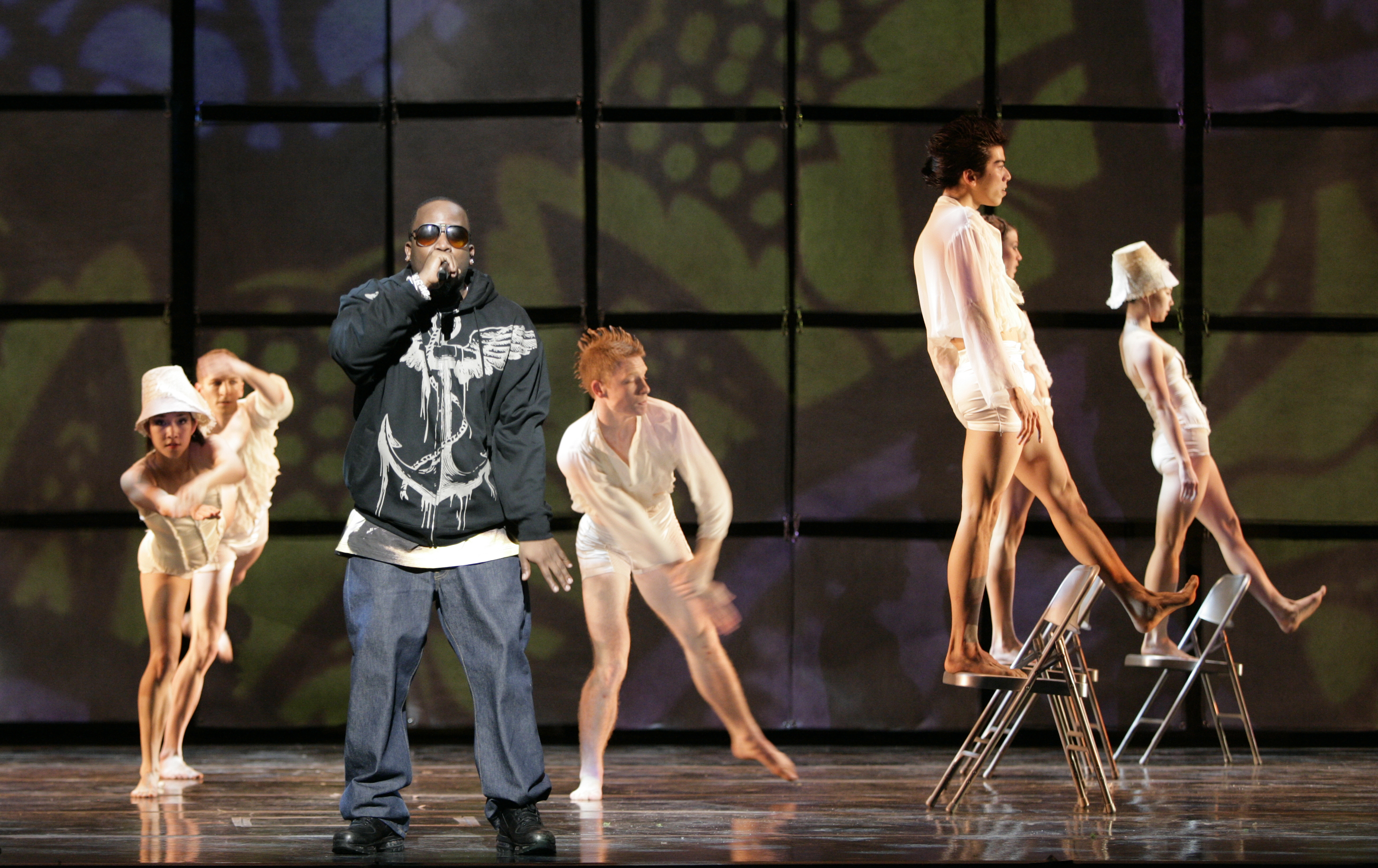

| big featuring the Atlanta Ballet with Big Boi. |

Big Boi Ballet

by Philip Auslander

Although ballet is stereotyped as a traditionalist, “high-art” form, modern choreographers have long engaged with

social dance and popular music, including rock, jazz, and theatre music. Beginning in the 1930s, New York City Ballet founder

George Balanchine frequently used jazz and popular music and, in 1999, the company celebrated its 50th anniversary with a

program that included pieces choreographed to Duke Ellington and a score commissioned from Wynton Marsalis (which had premiered

in 1993) alongside a new production of Swan Lake. In the current ballet season (2007-8), Ballet Memphis danced to the

music of Eric Clapton, Radiohead, and INXS, while the National Ballet of Canada presented Rooster, incorporating music

by the Rolling Stones. Decadence Theatre, an all-female dance company based in Brooklyn, NY, has been doing productions that

meld hip-hop music and dance moves with ballet and other forms of theatrical dance for about five years.

big, the Atlanta Ballet’s recent collaboration with Antwan Patton, known as the rapper Big Boi, half of the Atlanta-based

hip-hop duo OutKast, exemplifies the ballet world’s ongoing engagement with popular music and culture. For me, the interest

of such cultural encounters lies neither in the mere fact that they happen nor primarily in what they may mean for the political

economy of the arts (e.g., the possibility that big will attract a younger, more racially diverse audience to the ballet)

but in the opportunities they provide to consider the terms under which such encounters take place. When ballet meets popular

music, on whose turf do they meet? What rules govern such meetings, and who sets them?

It is worth noting, for example, that prior to Marsalis, the New York City Ballet did not work very much with jazz musicians

but drew on music in the orchestral tradition that was influenced by jazz, composed by Igor Stravinsky, Richard Rodgers, George

Gershwin, Morton Gould, and Aaron Copland, among others. During its 50th anniversary celebration, the New York City Ballet

danced to symphonic arrangements of Ellington rather than big band versions; even Marsalis’s piece is scored for an

orchestra rather than a jazz group. This, along with the other examples, suggests that when jazz encounters ballet, it does

so on ballet’s terms, in the sense that jazz must be accommodated to the orchestral idiom. This is not necessarily a

one-way street, culturally speaking. The American Jazz Museum in Kansas City, Missouri is not alone in describing jazz as

“America’s classical music,” a claim that is surely reinforced by the assimilation of jazz to the traditions

of symphony and ballet.

Rock music, it seems, is a somewhat different story. Bringing rock onto the dance stage, Ballet Memphis and the National Ballet

of Canada used recordings by Clapton, the Stones, and others rather than orchestral arrangements of their music. This implicitly

respects the way rock culture is built around recordings, the way it is difficult to distinguish the musical work from

specific performances of it by particular artists. A dance choreographed to the music of the Rolling Stones invokes the Stones

as performers and personalities as much as it does their music, even in their physical absence. Because rock cannot be assimilated

to the symphonic tradition as jazz apparently can, ballet must meet it at least half way.

One distinctive feature of big, choreographed by Lauri Stallings and presented April 10-13, 2008, was that Big Boi

and other singers and rappers from his Purple Ribbon record label not only leant their voices the Atlanta Ballet but also

shared the stage with the dancers (the production also featured a live band). Despite their mutual presence, the dancers and

musicians did not interact very much, but seemed to occupy parallel planes that occasionally intersected. The rappers and

singers moved, for the most part, like rappers and singers—they did not perform ballet. Likewise, the choreography was

ballet, often by way of Broadway—there were moments that evoked Jerome Robbins or Bob Fosse and a rather explicit, umbrella-waving

homage to Gene Kelly’s “Singin’ in the Rain.” The simultaneous presence of these very different styles

on the same stage underlined the specificities of each vocabulary of movement. The conventions of hip-hop performance--the

pacing, strutting, and gesticulation--were framed by contrast with the very different conventions of ballet. In one wonderful

moment, Big Boi worked his way purposefully from upstage right to upstage left and back again during a romantic duet danced

downstage. His presence was entirely extraneous to the dancing taking place in front of him, yet made perfect sense in the

context of the production. This was cultural encounter and collaboration as juxtaposition rather than synthesis.

There were ways in which the deployment of elements in big reflected the heterodox construction of hip-hop itself.

Just as hip-hop incorporates live playing and a wide range of recorded sources, sometimes including jazz, classical music,

and opera, and layers them one upon another, so big was constructed in layers. The corps de ballet was often choreographed

to the beat rather than the singer’s melody or the rapper’s rhythm, replicating the division of labor in the music.

At some moments, computerized lighting generated a rhythmic visual pulse constituting yet another track that functioned independently

of, yet in synch with, the other things going on.

In big, hip-hop met ballet on ballet’s turf—the event took place at the spectacular Fox Theatre in Atlanta,

a venue devoted mostly to musical theatre, mainstream popular music, and dance, and was part of the Atlanta Ballet’s

subscription season. But as I have suggested here, the performance itself strategically redefined the stage of the Fox as

much as possible as a culturally neutral space in which each form could speak in its own language and acknowledge the other

without having to surrender territory to it. These made the moments of intersection all the more poignant, as when a dancer

leapt suddenly into Big Boi’s arms, incorporating him into the dance for a moment, or when the Afro-Futurist pop diva

Janelle Monáe appeared in a NASA-silver tutu and executed some ballet steps while belting out her song “Sincerely Jane.”

And it must be said that the finale, in which Big Boi and company raised the roof and brought down the house with everyone

on stage, was much more like the closing moment of a hip-hop concert than a ballet.

Philip Auslander teaches performance studies at Georgia Tech.

www.philipauslander.com

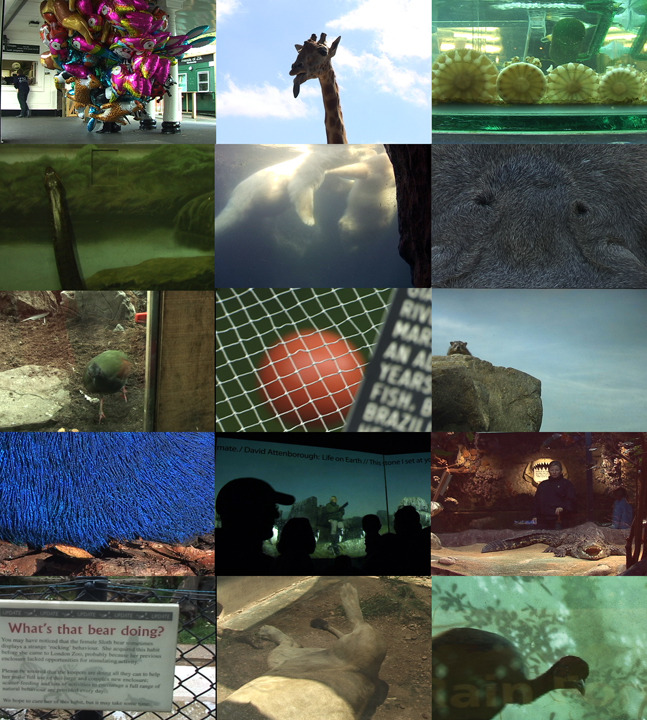

| Work by Nina Katchadourian |

|

Inroads:

Nina Katchadourian and the Bedevilment of Space

by

Cinqué Hicks

I remember the exact moment the outside world became real for me by

way of an encounter with a map at the local library more than two decades ago. Flipping through various encyclopedias and

atlases, I came across a page in one especially massive tome in which a tiny stretch of the Normandy coast was rendered across

a spread at a scale of some 2 feet by 3-and-a-half feet. This was a region of the earth that I had never seen rendered larger

than perhaps as a 1-inch square, and I was startled by the explosion of space I was witnessing. Like most children, I had

imagined that I took up an enormous amount of space in the world, and that the world was a small, knowable, controllable extension

of my own psyche. Encountering this map, I was obliterated, brought to a state of total insignificance. It was the first time

I remember ever being conscious of the fact that things exist not as a result of my contact with them, but because of the

existential primacy of the thing itself. In other words, the world “out there” was real, not an abstract fiction,

and it didn’t particularly need me in order to exist.

Brooklyn-based Nina Katchadourian’s multiform artistic practice taps into this peculiar ability of maps and displays

of information not only to reflect, but to condition particular psychological realities. Katchadourian grew up in Northern

California, making an annual pilgrimage to her family’s cottage in Finland. From an early age, she learned to measure

time in terms of space and to regard language as a plaything, always unfamiliar and provisional. Through installation, photography,

sculpture, and digital media, Katchadourian makes a circuit between the familiar and unfamiliar, confounding contexts, and

rendering information profoundly uninformative, all to explore how we know what we think we know about where we are.

I spoke with Katchadourian recently and asked her if she thought there might be something in our cultural moment that is

calling for this reimagining of space.

Nina Katchadourian: To give an obvious answer, it must have something to do with the fact that it is a

lot easier to move around, faster than ever before to more places than ever before. Or even, to really spout out a cliché,

“from the comfort of your own home” via the internet, we have access to so much stuff and information, even maybe

a sort of false sense of connection to other places far away. But I do sort of feel like from your armchair you have that

now in a way that we completely take for granted. I can’t even remember anymore when I didn’t have email. It’s

funny I remember when I got it, and I think about people growing up never not having had it. I think that all our methods

of communication have changed: the pace of it, the expectations for it, the tolerance for the volume of it, all of this kind

of stuff.

Another really important part of my summer experiences [in Finland] is that I grew up writing really long, proper letters

back and forth to my friends when I was gone. In this kind of correspondence you had to learn to wait a week or two to get

a letter back from someone, even if they wrote back right away. It was not going to be an instant response. Time and place

for me, and distance, I think we’re very much shaped by that feeling of a physical thing traveling across space to get

to you, from my friend in California to me in Finland. The way that that gap got measured by mail was important as a kid.

The same friend now who lives in Australia can call me on her cell phone ‘cause she’s got some plan where she

has an American number and I can call her whenever as long as the time zone works out.

It’s funny: it doesn’t necessarily make it any less mysterious to me though that I’m talking to her in

Australia. It’s still kind of a weird buzz around thinking that she’s under the globe and I’m up here. We

like to think that we’ve gotten so used to this and none of this is weird anymore. But I’d have to say that there

are still tinges for me of, “Oh my god, she’s on that country down there shaped in this way that I can see in

my mind’s eye.”

|

| Nina Katchadourian |

Cinqué Hicks: That makes me think that when you cut out the longest road in Finland

and curl it up into a petri dish, or cut out the highways in Austria and put them into the shape of a heart, that in some

ways is actually a more accurate representation of how we experience space.

NK: I think there are a few things that are connecting to the question you’re asking me. One is

that the very first map I ever made—I made this when I was a senior in college and it was in response to this assignment

we had in an art class—was this big paper world map that I’d cut apart and completely built up again with all

the countries in the wrong place but with an eye toward also making it look, initially, like maybe not a whole lot of change.

So it was playing with a lot of bigger geographic forms that were familiar, like the way that North America works into Central

America works into South America. Those shapes were often still kind of recognizable but different things had been substituted

in. It’s called World Map. It’s an important one ‘cause it’s what started this whole map thing.

It’s not strange for someone like me probably, with the family that I have, to end up scrambling the world around and

having that seem in fact kind of normal looking. I mean that is the way the family background has played out.

But the other thing about maps is that I think that the reason I make a lot of maps that connect anatomy or that look like

the Austria-heart one or Finland’s Longest Road, which is in this petri dish—there’s all these connections

to science and anatomy and biology—is that I think there is this funny leap of faith that is really similar for me when

it comes to studying geography and thinking about, for example, the shape of an organ inside you. I’m kind of just taking

it on someone else’s researched opinion that Austria really is that shape that I see on the map or that my heart really

is that thing that beats inside me that I can’t see or quantify but that supposedly is that shape. That may be different

for a doctor, it may be different for an astronaut who can see these things with their own eyes from space. I guess that’s

the best term I have for it, this sort of “leap of faith” feeling of, “Okay, I guess that’s what’s

out there.” That’s what’s funny about maps. They’re never really a view of a subjective experience

on the ground. It’s an impossible view from above. And I was for a long time making maps that were trying to deal more

with that really super-subjectivity and, ultimately, maps that were un-navigable and un-useful because they were so subjective,

but where it was more about walking a line on the ground and tracking that versus trying to get this big overview where

all these things are simultaneously down there.

CH: And then the other thing about the overviews, and the maps as seen from a distance is that really they’re records

of power. And they’re records of how power has been used and misused and deployed in any number of circumstances. Clearly

these lines don’t literally exist on the face of the planet, but they exist as records of how districts have been administered

in certain ways and how people have been categorized in certain ways.

NK: Absolutely. They’re also really interesting things in the history of [maps]. I was reading a

lot for a while on the history of how Australia got mapped. It’s such a great example of how we sometimes go sailing

out in search of something that we hope is going to be there but we’re not sure it’s really there. What happened

was that there was this Enlightenment assumption that the world is a rational place and there would be the same amount of

landmass in the Northern and the Southern hemispheres, which turns out to not be true. There really is just less landmass

in the Southern hemisphere, but there was this idea for a long time that there had got to be this big Southern continent that

hadn’t been discovered yet. It had to be out there. So, people set off sailing to find it, to find it, to find it and,

of course, with great hopes that there would be this spectacular place of great riches and all that. And, so, what happens

is that the Northern coast of Australia, eventually Captain Cook bumps into it finally. And gradually you can see the changes

on maps. They gradually start sailing around the whole thing and almost carving it out. But in the meantime there’s

all this projection and there’s all this hoping. So all kinds of things are getting drawn on the map before they’ve

actually been seen.

There’s this funny thing: does the map in fact make you go to find the place that you’ve already put on the map

even though you haven’t seen it yet? And this weird desire almost being the thing that spurs investigation. But I’m

not explaining this right. It’s almost as if the thing you’ve already pictured or hoped for becomes so real that

then you set off to find it.

CH: So the map emerges as a conversation between what’s actually physically there and what we hope is there.

NK: Yeah, that’s well put. With Australia they finally did figure out, “Oh, this is it. That’s

it!”

CH: I see a strand very strongly in your work, this strand of humor and funny things and jokes. And I wonder, though, what

the risk is. I wonder if you deal with the risk of being merely funny. And how you deal with simply doing a one-liner as opposed

to something more, or maybe you don’t care.

NK: This is an important question. I get asked about humor in the work a lot. My feeling is that it’s

a lazy viewer who believes that just because something is funny it means it can’t have content. I mean that’s

an absurd assumption to me. I don’t set out to make things that are funny. I’m happy if people laugh. That never

bothers me. I never think that’s a problem. But I don’t sit in my studio and think, “What can I do that

would be funny? Oh that would be funny!” That’s not the criteria. It’s not important that it end up that

way. It’s not a problem for me if people laugh.

I also would insist, though, that I’ve never made anything that’s funny that doesn’t also have a point

to make. So I find myself sometimes becoming on occasion irritated. Another review that came out, for example, about the project

I have calledTalking Popcorn, where, yes, I realize it’s a strange thing to do, to translate popcorn using Morse

code. It’s an odd idea. And I don’t mind if people think, “Oh my god. Wow. What?! Why?!” That’s

fine. But I remember a review that started something like, “What drug was she on when she thought of this? Har-har!”

And that’s fine, but there’s a lot in that piece being said, too, about the desire for us to have things mean

something, the problem of translation, the whole dilemma of when you’re trying to communicate in a language that you

don’t quite speak very well. How are you going to make sense of a situation like that, and all the meaning that we tend

to read into situations like that in order for things to make sense. The piece is a huge rumination for me on the desire for

communication to work out. That’s arguably a topic where a lot could be at stake. And certainly if you want to take

it to a global, political realm, a lot lies in our ability or desire to communicate or not.

I balk at the person who’s like, “Oh, I laughed, I’m done.” That’s what I call lazy viewing.

But that can be the problem. I really recognize that when people approach art with an expectation of just “I’m

here to be entertained” then once they’ve laughed sometimes they think they’re done. And to me that’s

only the hook. It’s the hook but it’s not the whole story.

CH: In the popcorn piece that comes right back around to being in Finland but Swedish [which you speak] not being helpful

there. In foreign places where you don’t speak the language and the trouble that that brings.

NK: Right. Trouble and sometimes a whole lot of glee and humor. I spent half of my junior year abroad in

college in Indonesia. I went to study this musical instrument I had gotten really obsessed with in college and I had to learn

Indonesian in like ten days. Because it’s a pretty simple language structurally, it was possible to become reasonably

conversational in a pretty quick amount of time. But, my god, were there situations where I would sit there going, “I

hope we’re having the same conversation. I think we are, but I really hope we are ‘cause otherwise this is pretty

strange.” [both laugh]

CH: I want to ask one last question, which is, Where are you headed in the future? What’s the next step for you?

NK: My [upcoming] project for Marfa [coming September 2008 under the auspices of Ballroom Marfa in Marfa,

Texas] is a whole other story. I lead another sub-life as a musician, as a singer. There’s moments in recent years where

the identities crossed over a little bit more. My project for Marfa is in some ways actually a music project. I’m advertising

a free jingle-writing service in papers and on the radio and around and about town. Anybody who wants a jingle for their business,

or for their club, or for some kind of community organization is welcome to contact me. Then with these people I hope to work

out different jingles to actually record them in Marfa. I’m going to get people to hopefully participate in their own

jingles. And then they’re going to end up on the radio there. So it’s kind of a way to explore the place, but

also to collaborate with people who are there. And in some ways just offer myself as a service to the people who are the locals

to put the word out about whatever it is they want the word put out about.

In terms of what’s coming up, there’re also things that are going to be very specific responses to specific situations.

I like that. It always stretches me to sort of try to work that way, especially when I don’t know the place.

I'm tempted to say that it is more important now than ever before to interrogate how we map and represent the

external world. But the truth is this has always been a critical practice; the rise and fall of empires, the extinctions of

entire races have pivoted on how space, language, and culture have been mapped. The work of Nina Katchadourian points to

that fragile process, plays with it, and leaves us dancing on the ground that shifts beneath our feet.

Cinqué Hicks is an artist, writer, and curator whose article "Code Z, Arts Reporting, and the End of Black Art" appeared

in the October, 2007 issue of The Art Section.

My Job: Painter

by Glenn Goldberg

|

| Glenn Goldberg |

I grew up in the Bronx, New York City. I was not taken to cultural venues other than the school museum trips that happened

in the public schools that I attended. I grew up hanging out on the corner after school, playing sports (baseball, basketball

and handball), meeting up at Jack’s Candy Store in the neighborhood, and dating the captain of the cheerleaders at James

Monroe High School. I dropped out of college, traveled (hitch-hiked) across Canada and the U.S., and began drawing, painting

and playing music at that point. Campuses were active politically (war in Vietnam) and there was much experimentation with

drugs, music, and sex. It was during this period that art began to captivate me.

Art is the main work channel through which I grow. It involves devotion, a work ethic, curiosity, soul searching, independence,

self acceptance and courage. It is loaded with many ups and downs and presents many challenges along the way. I could never

have predicted the work that I have made and am currently making. Despite how internally driven the process is, outside forces

help to shape and alter its path, thus the surprises that occur. My paintings are a hybrid of American training (via European

tradition) plus influences from American folk traditions, Asian art, African art, children’s tales and utilitarian objects.

I view art as an offering that ideally does not point back to its maker. My job as a painter is to get out of the way and

fabricate a viable and honorable condition. Other bodies of work are involved with tinkering, hobbies, boyishness, play, and

work that hovers without knowing its purpose. They usually are manifest in 3 dimensions, photos, posters and other concoctions.

Nature is important as a guiding force, but the need to be in the midst of it is not strong. I grew up in the concrete realm…schoolyards,

playgrounds, outdoor urban settings. I need to get away, but am a city boy. Perhaps the nature references in my work (flowers,

birds, mother forms) are a function of nature deprivation syndrome. I imagine I suffer from that and thus need to fabricate

my own natural scenes that become first person soul feeders. As a New York artist, I experience nature by finding a blade

of grass that grows in between the concrete slabs on the sidewalk, or by traveling to exotic places (defined as anywhere with

water, trees and a squirrel or two).

When I make a drawing on a wall, it brings back the days of it being disallowed as a child. So there is an element of taboo

to that act. It also will be painted over (much like the sand mandalas of monks that get tossed away) never to be again. It

is also free, not for sale, and viewed by few. That gives it a special place somehow. The fact that there is no object (support,

cloth, wood, paper etc.) makes it very nice also, without that stuff in-between the image and its holder/support structure.

My minimalist works were a way for me to start over…start at the beginning after years of filling up the whole rectangle

with forms and colors. So the paintings became about an image on a white, creamy ground. I became interested in figure and

ground in a rather pure and simple way. The surface became a bed or a blanket to house and coddle an image. I also was interested

in the semantics of forming, e.g. how a line or shape acquires meaning and/or reference. I have always wanted to paint pictures,

whether literal or implicitly referential, and starting off with nothing was a way to explore the magic of that process. Minimalism

and its interest in how a work begins was a very exciting and helpful idea for me. It cleaned my slate and wiped out many

assumptions. Also, the sparseness and efficiency of Chinese art dovetailed neatly with what I took from minimalist ideology.

|

| Work by Glenn Goldberg |

I believe strongly in the experimental aspect of making work and living. We try

things, explore, ask questions, fail, stumble, prevail, and actually win sometimes, which is a funny way to look at making

art or life. Exhilaration occurs as a function of the stretch, the reach, the attempt. Unfortunately, so does falling on one’s

face. I like the gamble of art as a life choice, and the secondary gambles that get played out in each piece. As a result

of that belief, I accept the range of works that I have made despite having preferences. As we grow in the realm of self-acceptance,

regrets seem to float away one by one. I feel that way about my work. All of the things that I have made are part of the richness

of my fortunate life…they don’t have to be good or meaningful all the time, they just have to be a function of

my allowing myself to live.

I work with a bucket of water, a handful of brushes, a surface to make a picture, and some colors. When I build, I build with

my hands and generally use wood, foam, fabric and/or glass. The process is not elaborate. Complexity is a function of the

addition of one decisive move after another. I used to jump into complexity quickly and try to fight my way out. Now I build

complexity brick by brick, touch by touch. I imagine that is somewhat ritualistic. It feels like a practice akin to chanting,

working out in the gym, breathing, pitching or shooting. Shooting is part of the game and as one shoots several times, a game

is ultimately formed (along with all of the other acts that comprise the game). Making art is a replacement for religion,

shamanism, and other forms of spiritual/alchemical development. It is not healthy for art to be driven by negativity, cynicism,

decadence or fighting some fruitless man vs. nature battle. For me, making art is about heading towards the ideal, gift giving,

offering, and a degree of selflessness, awe and statement of appreciation. It is qualified and absorbs other deviant qualities

but it is best to try to limit those forces if we are able.

Sports are important to me, particularly team sports. I am interested in leadership, sacrifice, repetitive tasks, improvement,

fair play, development, coping with winning and losing, and working towards goals day by day. Despite the solitary nature

of my work, many of the things I have learned and have taught (I have coached a lot) have been learned through sports. Perseverance

is another great quality, as are humility, focus, patience, relentlessness, purpose and respect. It is what we do, not what

we say, that counts the most. As my father taught me in relation to baseball: “Do your talking with your bat!”

|

| Work by Glenn Goldberg |

Glenn Goldberg is an artist who lives and works in New York City.

Glenn is working with Michael Klein. michael@michaelkleinarts.com

|

|

|