|

|

|

| Work by Brazilian artist Adriana Varejão. |

Introduction

by Deanna Sirlin

Editor-in-Chief The Art Section

A very intelligent curator once told me that the longer he stays in the art world, the more interested he becomes in the viewers’

relationships to the work of art. As an artist, I loved that concept, and it has certainly stayed with me. In this month’s

edition of The Art Section, we present three different relationships to the work of art for consideration. First, we have

sound artist/composer Jason Freeman on his own work, the web-based software program entitled iTunes Signature Maker (iTSM).

Since this program constructs a musical work by algorithmically assessing a listener’s musical preferences, it proposes

a very intimate relationship between audience and art work. You can experience Freeman’s diverse taste in music and

sound here, and also try iTSM online yourself. Next is Brazilian and, importantly, Rio-based artist Christina Roiter discussing

the difference between Rio and Sao Paulo from her local perspective. Roiter’s perception of the art in current exhibitions

in Rio is inflected through her understanding of what it means to be in one place as opposed to the other. I wonder, are there

two other cities that function comparably as the yin and yang of their country’s art world? Finally, we have critic

Phil Auslander’s fast train of thought on a Perry Vaquez Victor Payan’s work “Keep on Crossin’”,

presently on view in the exhibition TransActions: whatever at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta. Read him and watch his

mind move from the work to an extended speculation on cross-cultural currents. Interestingly enough, following the thread

of Auslander’s thinking is a bit like listening to the result of Freeman’s software’s sampling of his musical

taste to produce a concise musical portrait.

All my best,

Deanna

www.deannasirlin.com

What I Listen To

by Jason Freeman

People often ask me what music I listen to, but I find it difficult to describe my eclectic taste in words.

I can say that I like Thelonius Monk and Ella Fitzgerald and Béla Fleck and Beethoven. I do like music by these musicians,

but they present a distorted view of my taste. They are simply the names most likely to be recognized.

I can also say that I like Eleanor Hovda and Faradj Karajev and Michael Gordon and Josquin. I do like music by these musicians,

but most people have never heard of them. They make me seem like an aloof, academic snob.

I can also say that I like quiet, sparse music, that I like conceptually-driven work, that I appreciate clever allusions and

thoughtful references. I do like all of these things, but it is difficult to extrapolate my musical tastes from such vague

descriptives.

So instead of answering this question with words, I now answer it with sound. In 2005, I developed a web-based software program

titled iTunes Signature Maker (iTSM). It analyzes the music in a user’s iTunes music library, both in terms of her listening

habits (play counts, star ratings, play dates) and the audio content of the files themselves (spectra). It uses this information

to quickly generate a short audio file that mixes together segments of the user’s favorite songs to create a concise

portrait of her musical taste in sound.

The software is not perfect by any means. Its algorithms are crude and simplistic, because I wanted them to execute in a few

short minutes. (Who would be willing to let their computer churn away for days on end just to generate an iTunes signature?)

It relies heavily on personal listening data tracked by iTunes, but this data can miss important details of listening habits.

(If someone has played a song a thousand times, iTunes does not know whether it was played mostly last week or mostly many

years ago.) And it cannot include songs purchased through the iTunes Music Store that are protected by digital rights management

(DRM).

iTSM’s worst signatures resemble advertisements for a radio station or a Time-Life music compilation: short snippets

of songs quickly cross-faded together. iTSM’s best signatures are themselves interesting sonic objects, with individual

fragments linking together to form larger musical phrases.

Even though iTSM’s signatures are not perfect, they are still much better than words at describing my musical tastes.

In fact, sometimes I wish they were less accurate: the inclusion of some musical works in my signature embarrasses me. I am

proud that my signatures often include music by Charles Ives. I am not as proud that they often include covers of Leroy Anderson’s

holiday classic, “Sleigh Ride.” But in the end, my signatures instigate self-acceptance: all of this music is

an important part of who I am, and all of it is beautiful to me.

I intended iTunes signatures, of course, to be mechanisms for both self-reflection and for self-expression. In the spirit

of the latter, I encourage users to share their signatures in an online gallery, to post them on their weblogs and web sites,

and to discuss them with each other. One of my own signatures serves as my mobile phone ringtone. These signatures, ultimately,

are part of larger cultural trends toward building online identities around listening preferences.

The five tracks presented here, collectively titled “What I Listen To,” express my eclectic musical tastes. It

is a series of short experimental sound works that algorithmically stitch together bits and pieces of the music I've listened

to. I created them during the development of the iTSM software; each provides a different snapshot of who I am and what I

listen to. The algorithm considered both my listening habits and the spectral content of the sound files themselves when creating

these pieces. The results are a mix of smooth textures, chaotic collages, and embarrassing revelations about my taste in music.

December 3, 2005

October 24, 2005

November 30, 2005

October 24, 2005

November 19, 2005

iTSM was commissioned by Rhizome. The Rhizome Commissions Program is made possible by support from the Jerome Foundation in

celebration of the Jerome Hill Centennial, the Greenwall Foundation, the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, and the

New York City Department of Cultural Affairs. Additional support has been provided by members of the Rhizome community.

iTSM is available at www.jasonfreeman.net. Additional technical information on the software and complete source code is also available at that site.

Jason Freeman is a composer and sound artist. He currently serves as an Assistant Professor

in the Music Department at Georgia Tech’s College of Architecture.

www.jasonfreeman.net

| Work by Nuno Ramos |

|

Rio Versus São Paulo:

Rivals or Complementary?

by

Christina Roiter

Is the traditional competition between the two main poles of the Brazilian art world—Rio,

the center of art production and São Paulo, home to commercial galleries--ultimately beneficial for Art?

Rio is the Americas, young, vital, energetic, looking forward towards the future;

São Paulo is Europe, conservative, steady, slow pace, elegant, chic....

Rio de Janeiro has been inspirational for artists in Brazil, the center for Art creation, whereas São Paulo is known for being

where Rio sells the art created here....

Rio is an organic city, lively, surrounded by spectacular vistas of lush, green tropical rain forests, pristine beaches bathed

by the Atlantic ocean, and superb girls in “dental floss” (as the g-string is called here) swim suits, known for

its urban quality and effervescent night life. It is the capital of music production, where the leading musicians choose to

live. And for these reasons, it evolved over the last decades into the capital of art production in Brazil, although in recent

years some other cities are revealing some new and good production.

São Paulo is the megalopolis, the financial center, where the biggest industries have their main offices, where the money

flows. A very urban city of skyscrapers, heavy traffic, pollution, and scarce green vegetation.

It is the competition between these two most important cultural centers of Brazil that drives the art engine here.

See for instance the number of very important commercial art galleries in São Paulo in comparison with Rio. Far fewer….

Rio has a few, very good galleries, like the ones owned by art dealers Sylvia Cintra, Laura Marsiaj, Heloisa Amaral Peixoto,

Mercedes Viegas, and Anna Niemeyer, who struggle to sell in our charming, but commercially less favored city, at least where

art is concerned.

In the last decades, Rio has also gained several important cultural centers, like the Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil (CCBB),

owned by the Brazilian state owned bank Banco do Brasil, which has sponsored large and important exhibitions.

On March 3rd, 2008, CCBB has brought in from Berlin´s Ethnological Museum, which is considered one of the most important of

the world, the exhibition The Tropics – Visions from the Center of the Globe, including 130 ancient works of

Art from countries in the tropical regions of the planet (Africa, Asia, Americas and Oceania) and 87 works of art by 23 contemporary

artists from several countries, among them paintings, photos, sculptures, videos and installations. The exhibition proposes

a dialogue between ancient and contemporary art. Alfons Hug, who did the curatorial work for recent editions of the São Paulo

Bienal, Viola Konig, and Peter Junge were the curators. The artists include: Caio Reisewitz, Candida Höfer, David Zink Yi,

Fernando Bryce, Fiona Tan, Gerda Steiner & Jörg Lenzlinger, Guy Tillim, Hans-Christian Schink, Lucia Laguna, Marcel Odenbach,

Marcone Moreira, Marcos Chaves, Maurício Dias & Walter Riedweg, Milton Marques, Paulo Nenflídio, Pilar Albarracín, Sandra

Gamarra, Sherman Ong, Theo Eshetu, Thomas Struth and Walmor Corrêa.

|

| Work by Hilal Sami Hilal |

Another big show happening in CCBB is about one of the pioneer photographers in

Brazil, Marc Ferrez. It’s worth attending for the collection of 396 photos of Rio in the turn of the 20th century,

and for those aficionados of the history of photography.

Hilal Sami Hilal, a great artist known for his sculptural structured paper nets, is showing at the Museum of Modern Art, the

MAM, Rio. This time he is doing a collective work, with the collaboration of four teenagers from an Apprentice Project of

Vale Museum in his home state of Espirito Santo. Names of family friends form the structure of some works, like the copper

and paper books in one of the exhibition’s nuclei, the library. The books are created from sheets and names piled like

pages. All identical, they intensify the empty spaces, creating a sense of profundity.

Rio is hosting the 2008 edition of the International Festival of Electronic Language, sponsored by Spanish Bank Santander,

in a partnership with the Cultural Center Oi Futuro,

owned by the state-owned cellular telephone company, Telemar. The Festival promotes and stimulates aesthetic production in

electronic and digital culture. It’s the largest art and technology festival of Latin America. This year, it presents

the project Se Liga (Be Connected), inviting the public to the cities where the festival is taking place, to the involved

institutions, the virtual world, the web and electronic art.

Turning to private galleries, we have a “paulista” gallery (from São Paulo) showing in Rio. The internationally

renown Fortes Vilaça has surrendered to Rio´s charms and opened the Casa do Saber (House of Knowledge), a new meeting place

for the elite to attend courses in all types of contemporary matters like philosophy, music, art and also to see and be seen.

The works exhibited are by excellent artists like Adriana Varejão, Ernesto Neto, Janaina Tschäpe, Luiz Zerbini, Nuno Ramos,

Sara Ramo, Valeska Soares, and Vik Muniz.

I know I´m raising a big issue by comparing and contrasting the two cities’ art scenes and I know that Paulistas and

Cariocas can get very angry with each other, and make a lot of jokes at each others’ expense.

In fact, let’s get serious.

Although Rio is considered the more “creative” city, the art production in São Paulo is very significant, with

great islands of creativity and leading conceptual artists like Tunga, Nelson Leirner, and Leda Catunda.

The bipolar condition between the two cities is constantly shifting; the pendulum keeps searching for a balance, and has even

moved outside their borders. Cities like Curitiba, Goíania, Salvador, and Recife have intelligently kept traditional competitive

exhibitions rolling, which now substitute for the biggest and second most important national art show, The Salão Nacional

de Artes Plásticas in Rio. The presence of these exhibitions brings art production to their cities as well, not only to Rio

or São Paulo.

To be continued …

For more information please visit the following websites:

MAM: www.mamrio.org.br

Casa do Saber: www.casadosaber.com.br

Laura Marsiaj Arte Contemporânea: www.lauramarsiaj.com.br

Christina Roiter is an artist based in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

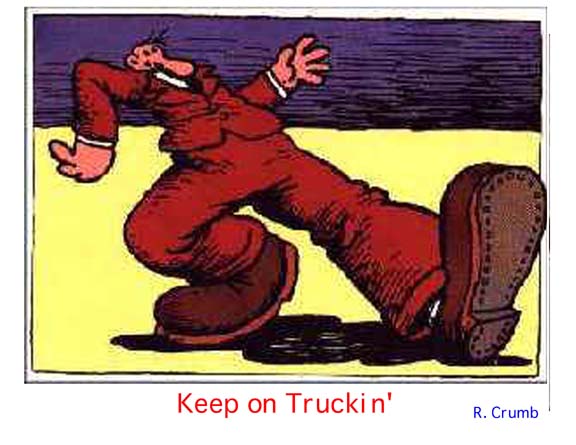

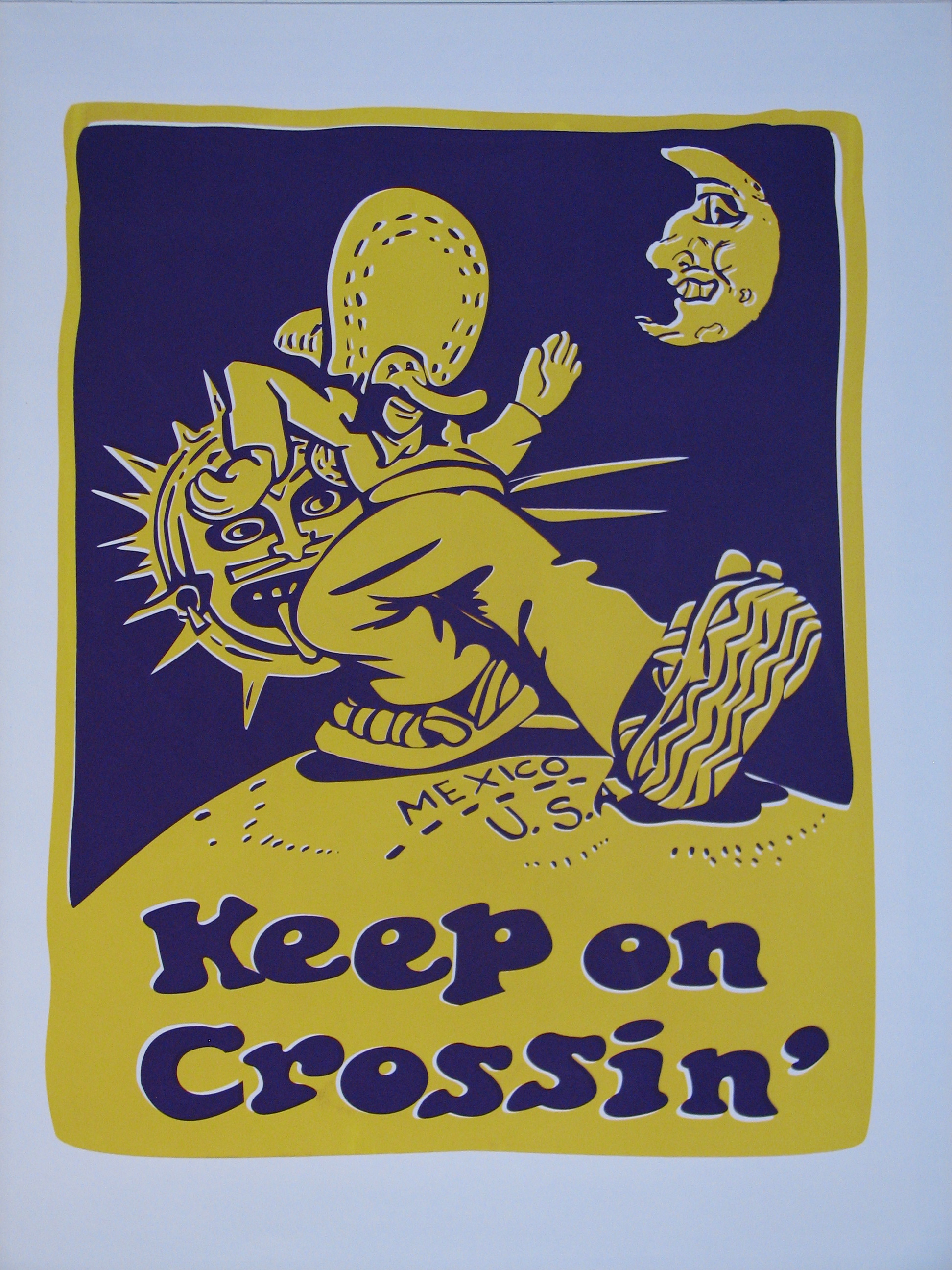

Keep On Truckin' 'N' Crossin':

|

| Photo: Perry Vasquez |

A Meditation on Cultural Miscegenation

by Philip Auslander

Seeing the wall of Perry Vasquez’s “Keep On Crossin’” prints, part of Vasquez and Victor Payan’s

Keep On Crossin’ Project, in TRANSactions: Contemporary Latin American and Latino Art at the High Museum of Art recently,

I was struck by the way Vasquez brought together two of the biggest names in graphic art of the 1960s: Andy Warhol and R.

Crumb. This is a provocative blend: Warhol, the graphic artist turned art world operative, and Crumb, one of the creators

of the genre of underground comix, represent two very different and, in some ways, mutually antagonistic cultural contexts.

Vasquez’s seemingly infinite replication of the image in different color schemes is Warholesque, but the more compelling

aspect of the piece is his appropriation of the phrase “Keep On Truckin’” and the happy figure strutting

his way through life from Crumb. Vasquez and Payan translate “Keep on Truckin’” into “Keep on Crossin’”

and Crumb’s anonymous suited men into a generic Mexican truckin’ his way across the border. Crumb first used the

expression, and those figures, in the mid-1960s; they were taken up by the hippie subculture as an expression of combined

determination and insouciance. Vasquez and Payan have repurposed them to address the issues surrounding illegal immigration.

At one level, then, “Keep On Crossin’” is a pair of Chicano artists’ appropriation of an older white

artist’s work, and a 21st century reworking of an image and idea associated with a mid-20th century subculture through

the eyes of a currently embattled community. But as I looked at the wall of images, I thought about the dense web of cultural

allusions and appropriations that lies behind it, a web that entangles, in one way or another, the East and West coasts of

the United States, and cultural expression associated with African-American, Mexican-American, and white American subcultures.

Crumb did not coin the phrase “Keep on Truckin’” (indeed, a court of law eventually found that the phrase

is in the public domain and that Crumb had improperly earned royalties from it, which he was compelled to pay back). It originates

in a 1936 blues recording by Blind Boy Fuller and appears in a number of blues and novelty records of the era, where it is

used as sexual innuendo. In the early 1970s, the San Francisco rock bands The Grateful Dead and Hot Tuna had hits built around

the phrase (respectively “Truckin’” and “ Keep on Truckin’” a pastiche of Fuller’s song and others related to it). These bands’ use of the phrase was undoubtedly inspired

by Crumb but it also represents another means by which it found its way into the hippie lexicon.

Truckin’ was also a dance step popular in the Harlem dance halls of the 1930s and 1940s (it was a shuffle step that

was incorporated into the Big Apple and served as the basis for the Suzi-Q). In 1936, Ina Ray Hutton and Her Melodears, an

all-female big band, recorded a song called “Truckin’” that referred explicitly to the way the “uptown”

(read: Harlem) dance had become popular “downtown” (read: among white people). Crumb, an avid collector of vintage

78 rpm discs from the 1920s and 30s--and a sometime musician whose band, R. Crumb and His Cheap Suit Serenaders, performed

such music--was undoubtedly aware of these sources and the way both expression and dance had passed from black culture into

cultural contexts dominated by whites. In short, the R. Crumb image is not the point of origin of the verbal and visual iconography

Vasquez and Payan appropriated; Crumb’s use of it was also an act of appropriation that furthered the cultural miscegenation

around Truckin’ that began in the 1930s.

|

| Monitos from the Keep On Crossin' Project. Photo: Perry Vasquez. |

Although I have been unable to determine whether the Truckin’ dance was taken

up by Mexican-Americans in Los Angeles during the 1930s and 1940s, it is clear that African-American popular culture had a

strong influence on the Chicano youth of the period. There was, of course, a well-established African-American community in

Los Angeles that welcomed visits from East Coast jazz and dance bands. These visiting musicians inspired the development of

an indigenous West Coast jazz scene but also numbered young Chicano dancers among their passionate followers. Another mark

of this connection between Harlem and LA was sartorial: the zoot suit, adopted equally by Harlem hipsters and pachucos in

LA.

Although the precise origins of the zoot suit are obscure, it is generally thought to have originated in African-American

culture on the East Coast—it is perhaps ironic that one frequently cited source is Clark Gable’s costume in Gone

With The Wind! In any case, it became an expression of subcultural status on both coasts, associated with African-American

youth on the East Coast and Chicano and Fillipino youth on the West Coast. In both cases, it expressed alienation from the

majority culture. According to Shane and Graham White, the authors of Stylin': African American Expressive Culture from Its Beginnings to the Zoot Suit, “Pachucos

created a subculture with a mysterious argot that incorporated archaic Spanish, modern Spanish, and English slang words. They

dressed in zoot suits, creating a distinct style that identified them as neither Mexican nor American, but that emphasized

their social detachment and isolation.” (In one of the sadder chapters of this story, the Zoot Suit Riots of 1943, violent confrontations between zoot suiters and predominantly white servicemen who questioned their patriotism in

time of war, began in Los Angeles and moved eastward, thus reversing the migratory pattern of the fashion itself.)

For George Sanchez, a participant in the LA scene, the pachuco’s zoot suit was not just an expression of cultural alienation: “[The

zoot suit] was [used] to really assert that, you know, we are here, and we want to make a statement about the fact that we're

here. But it was also, I think, a connection with other minority and poor youth in the United States. I mean, a zoot suit

was also worn by black youth, certainly worn by Malcolm X in New York. So there was a sense that the zoot suit was not just

a Mexican dress, it was also a connection with other minority youth, but in Los Angeles also was representative of the Mexican

American population. . . .” Along with music and dancing, the zoot suit was part of a vocabulary of social expression

shared by minority communities on the East and West Coasts.

My point is that Vasquez and Payan’s appropriation from R. Crumb is not an isolated occurrence. It is, rather, the most

recent link in a chain of complex interconnections among multiple social groups marked by both shared and appropriated cultural

artifacts, connections that span a continent, extend over more than 70 years, and have found expression in music, dance, fashion,

and the visual arts. Along this chain, meaning keeps on truckin’ and crosssin’: although verbal phrases, musical

styles, items of clothing, and visual images assume different meanings and associations as they are taken up by different

groups in different times and places for their own particular purposes, the new meanings add to and enrich the existing ones

but never fully supplant them.

TRANSactions, organized by the Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego from its collection, will be on

view at the High Museum of Art, Atlantathrough May 4, 2008. It will travel to the Weatherspoon Art Museum at the University

of North Carolina, Greensboro, where it will be on view from June 22 through September 21, 2008.

Philip Auslander teaches Performance Studies in the School of Literature, Communication, and Culture of the Georgia Institute

of Technology.

www.philipauslander.edu

|

|

|