|

|

|

| Interior of the Pavilhão Ciccillo Matarazzo, site of the São Paulo Bienal. |

Introduction

by Deanna Sirlin Editor-in-Chief The Art Section

This past summer, an Italian curator asked me when I thought Americans will stop talking about 9/11. I answered that I believed

that the response is still percolating in the American consciousness and perhaps the major works of art are yet to come. We

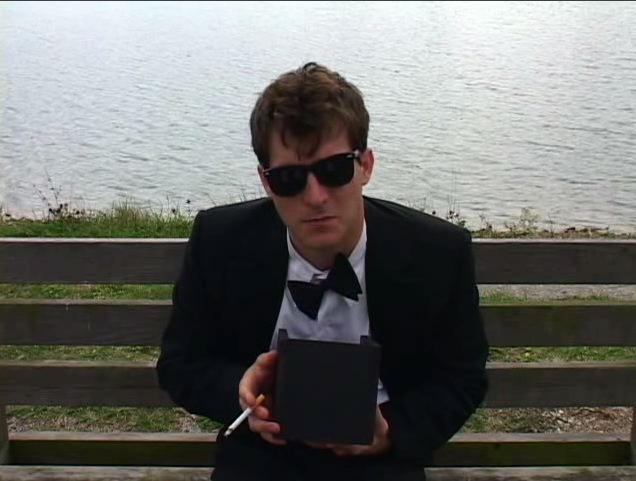

are very pleased to present Roger Copeland's powerful film The Unrecovered, a sometimes harrowing poetic reflection

on 9/11 and its aftermath. Copeland shares the ideas underlying the film, which he both wrote and directed; you may also view

a scene from the film by clicking on the image from it below.

We also offer two perspectives on the upcoming Sao Paulo Biennial one from myself and one from Brazilian artist Christina

Roiter. We would welcome more responses to this Biennale quandary.

And lastly, rounding out this issue, an essay in rock music historiography by Editor Philip Auslander, which sketches some

of the background issues to his book Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music (2006).

In addition, we are delighted to announce the first event sponsored by The Art Section, an exhibition, ‘Endless

Pleasure’ by Australian Artist Andrew Hewish to take place in Atlanta on February 29th and March 1st and 2nd For details,

please click here. We look forward to seeing you there!

To see a scene from The Unrecovered click on the image above.

Windows users may need to download Quicktime for Windows here.

The Unrecovered: A Film

by Roger Copeland

Director’s Notes for The Unrecovered

The Unrecovered is a feature-length, fictional narrative film about the psychological aftermath of 9/11. The film’s

title refers not only to the “unrecovered” bodies at ground zero, but also to the state of the nation-at-large.

Set in that hallucinatory period of time between September 11 and Halloween of 2001, The Unrecovered examines the effect

of terror on the human mind, the way a state of heightened fear, anxiety and/or alertness can cause the average person to

make the sort of imaginative “connections” that are normally made only by two distinct categories of human being:

artists and conspiracy theorists. In fact, by the end of the film, the audience is left to ponder some rather striking similarities

between creativity and paranoia.

I think of The Unrecovered as a horror film with a lot on its mind. Indeed, I’ve long dreamed of a movie that

would combine the tough-minded, analytical intelligence of Godard’s Two Or Three Things I Know About Her with

the shape-shifting, personality-morphing, dream logic of Bergman’s Persona (arguably the most sophisticated

vampire film ever made). An improbable marriage of Two or Three Things… and Persona-- that’s a pretty

good description of what The Unreccovered aspires to be.

There have of course, been many fine documentaries about 9/11; but very few works of fiction have attempted to chart the ways

in which the recurring images of that unimaginable day have burrowed their way into the nation’s collective unconscious.

The Unrecovered takes us deep into the dream-life of three different characters; but it does this without losing sight

of the public and political context in which these converging nightmares occur. News coverage of 9/11 on television, radio

or the Internet provides a constant “background” against which are “fore-grounded” three different

characters (who often absorb these streams of media imagery indirectly-- as if by osmosis.)

The film employs a collage-structure which repeatedly cuts back and forth between three separate narratives titled “Sound

and Silence,” “Wings and Roots,” and “Fog and Friction.” The first focuses on an artist (a composer)

struggling to create a musical work and a video diary about 9/11. The second story concerns a mother and daughter who were

abandoned some years earlier by their husband/father. The third centers on a survivalist/millennialist/conspiracy theorist.

The three characters and their stories embody three fundamentally different interpretations of the film’s title: (e.g.

The conspiracy theorist is convinced that 2001, not 2000 was the true “millennial” year and that the events of

September 11, 2001 mark the beginning of “end times” as foretold in the Book of Revelations.) For him, the unrecovered

bodies at ground zero have merely been wafted into heaven, as the initial stage of “The Rapture,” the climactic

event that he believes will trigger the appearance of the Antichrist and the ensuing “Tribulation.” (How and why

a devout evangelical Christian like himself was “left behind” is the question that propels his course of action

in the film.)

The composer (who refers to himself as a “recovering formalist”) is very much an aesthete, but one who realizes

that September 11th was one of those rare occasions when real life manages to put art on the defensive. He’s brave enough

to acknowledge what a lot of artists felt (but were afraid to admit) in the immediate aftermath of 9/11: “envy for the

death artists, envy of the sensory impact, global reach, and symbolic resonance of what the terrorists accomplished on September

11.” He’s especially obsessed with the (real life) comments of the composer Karlheinz Stockhausen who declared

-- a mere five days after the attacks-- that the events in New York and Washington amounted to “the greatest work of

art in Western History.”

By contrast, the twelve year old girl becomes fixated on the possibility that her missing father may have been living in

Manhattan under an assumed name, working in the World Trade Center; and as a result, he may be among the “unrecovered”

at ground zero. With the zeal of a modern-day Nancy Drew, she sets out to determine whether or not her father was killed on

September 11th. Early in the film, she watches a documentary at school about the ritual origins of Halloween. She learns

that “trick or treating” may have evolved from the ancient Celtic rite of Samhain when the spirits of those who

died in the past year wander restlessly in search of bodies to inhabit. And she suspects that if her father was indeed killed

on 9/11, then the most likely time for her to encounter his unrecovered spirit is on Halloween.

An obvious question: In what way(s) are the three stories “connected”? The audience (naturally) assumes that the

narratives will eventually intersect; and many clues appear along the way suggesting that the answers to questions raised

by one narrative strand may be found in one of the other two stories. Whether or not the characters really do cross paths

with one another remains deeply (and intentionally) ambiguous, because the film is ultimately about the question : “What

is and what isn’t, meaningfully connected post-9/11 in a fully globalized world?”

For the deeply paranoid conspiracy theorist, everything connects; there’s no such thing as a coincidence. For the composer,

whose sensibility is dominated by detachment and irony, no two entities are inherently connected, except by virtue of the

metaphors he devises in his art. This character is clearly an inhabitant of the digital age, an artist for whom the “cut

and paste” icons on the computer constitute not just print commands, but a philosophy of life. At one point he declares

“Cut and paste. I link, therefore I am.” Indeed, on one level, The Unrecovered is unabashedly a film

about the nature of metaphor, which (as we learn from the composer’s video diary) derives from the Greek root “metapherein,”

a transference of meaning which forges connections between otherwise disparate things or events). Ultimately The Unrecovered

is about the way in which metaphor, post-9/11, is fed by meta-fear.

This helps explain why the composer seizes upon Edward Lorenz’s so-called Butterfly Effect (“Does the flap of

a butterfly’s wings in Brazil set off a tornado in Texas?”) as the central metaphor for the way in which seemingly

insignificant events in one isolated corner of a globalized world can generate major repercussions thousands of miles away.

(Parenthetically, I might add that one of my chief ambitions in making this film has been to rescue the concept of “the

butterfly effect” from the many banal and reductive uses popular culture has made of it in recent years.) And in an

attempt to flesh out this metaphor, the composer performs a musical work by LaMonte Young in which a butterfly is turned

loose in the performance area. When listeners complain that the butterfly makes no sounds, the composer objects strenuously,

suggesting that it’s the audience’s responsibility to learn to hear the sounds the butterfly must surely-–at

some decibel level--be making. “The tornado, that’s easy enough to recognize,” he argues, “but how

do we learn to hear the sounds the butterfly makes when it flaps its wings?”

The question of what is and isn’t “connected” informs all aspects of this film-- its structure as well

as its content. For example, quite deliberately, none of the action in The Unrecovered is set in Manhattan or Washington

D.C.. This film is about characters whose connection to the events of 9/11 is entirely mediated by mass media. The Unrecovered

evokes a world in which an actual visit to ground zero is likely to feel anti-climactic, a world in which the endlessly

repeated, record-able , replay-able image of a thing is often destined to feel more authentic than the thing itself.

But… it also turns out that one of the characters may well be directly connected to one of the events that kept the

nation in a state of rising anxiety in the weeks that followed September 11th. The conspiracy theorist (who dubs himself “The

Bioevangelist”) becomes a self-professed avenging angel eager to speed-up the countdown toward “End Times.”

There’s reason to suspect that this character may in fact be responsible for the anthrax deaths in October of 2001.

Similarly, there’s also reason to suspect that the conspiracy theorist may be the twelve year old’s long-lost

father.

The actual incidents of anthrax exposure began to mount in late October; and October 31, 2001 was probably the most anxiety-ridden

night of trick or treating in recent memory. The Unrecovered reaches its emotional climax on Halloween, when the young

girl–in- search-of-her -father does indeed experience an “encounter with the dead”--but not the encounter

she had hoped for. The mental breakdown she suffers on Halloween night (when her identity appears to metamorphose into that

of a teenage Palestinian suicide bomber) is designed to re-frame the film’s most central question in terms of the

roots and branches of her family tree. Questions about “What is and what isn’t connected” morph into “Who

is and isn’t related” in a post-911 world where the traditional notion of “roots” has given

way to the more globalized concept of crisscrossing, globe-trotting “routes.”

Roger Copeland is Professor of

Theater and Dance at Oberlin College in Ohio. His books include the widely used anthology, What Is Dance? and Merce

Cunningham: The Modernizing of Modern Dance. His film Camera Obscura won the "Festival Award" at the Three Rivers

Arts Festival in Pittsburgh in l985 and in 1989, Recorder, a video adaptation of his theater piece The Private

Sector, was screened on WNET's "Independent Focus" series in New York City.

|

| Pavilhão Ciccillo Matarazzo, site of the São Paulo Bienal. Des. Oscar Niemeyer and Hélio Uchôa, 1957 |

Two Perspectives on the São Paulo Bienal

from Deanna Sirlin and Christina Roiter

On November 7th, the São Paulo Bienal Foundation announced

the appointment of Ivo Mesquita as curator of the 28th edition of its show, less than one year before its opening in October

2008. Mesquita’s proposal has fuelled an ongoing controversy and sharply divided the Brazilian art scene.

Instead of a traditional exhibition, the 28th São Paulo Bienal – to be titled ‘Em Vivo Contato’ (‘Live

Contact’) – will not contain any art objects: the 2nd floor of Oscar Niemeyer’s Bienal pavilion will be

completely empty; the basement will become a place for performances and film screenings, while the top floor will be turned

into library. During the 42 days of the event, Mesquita will organize a cycle of conferences focusing on how to organize biennials

in the future within the historical context of São Paulo Bienal and more than 100 biennials around the world.

--Fabio Cypriano, "A Void in São Paulo," Frieze Magazine

When I first was told that the 28th edition of the São Paulo Biennial would have an exhibition that would not have any artworks

in it, I must admit I was indeed taken aback. I have asked Brazilian artist Christina Roiter for the hometown take on the

curation and controversy (see below).

The title of this exhibition is ‘Em Vivo Contato’ (‘Live Contact’), and instead of works of art there

will be discussions of the meaning of Biennials. There are so many Biennials of every shape and size that have proliferated

all over the world--at last count, there were almost over 100 worldwide. Do we really need so much of this kind of curation?

Don’t get me wrong, I love to hate a good biennial as much as the next one and adore the world’s fair-cum-Olympics

that flexes its muscles in Venice, but do we really need all these Biennials?

However, proposing a series of symposiums for discussion of what biennials mean and why we do or do not need them ... well,

that just seems so last century!

This kind of discussion was presented in Atlanta in 1996 as part of a now defunct Arts Festival that had its crowning moments

in conjunction with the Cultural Olympiad that hot and crowded summer. “Artway of Thinking,” a collaborative team

from the Veneto Region of Italy, set up a series of dinners called Chow [Ciao] for Conversation for Culture. Curators Mary

Jane Jacob and

Michael Brenson invited the guests and session leaders and shaped the topics. I recall at the dinner someone asked, what kind

of boat is this curatorship that everyone seemed to be on. Brenson later wrote ”To me, however, a program constructed

around actual conversations in Atlanta between artists from outside the United States and individuals and communities not

normally engaged by museum art is not a repudiation of Modernism but both a radical critique and an extension of it.”

All I can think of is that Oscar Niemeyer’s Bienal pavilion will be completely empty.

Deanna Sirlin

Editor-in-Chief

The Art Section

www.deannasirlin.com

The recently nominated director of the São Paulo Biennialle, Ivo Mesquita, has decided to maintain the idea of the previously

appointed director Camilo Osório, who resigned after an intense outbreak of criticism in response to his decision to keep

the 2nd floor of the Pavilion, designed by architect Oscar Niemeyer, empty.

As a Brazilian artist observing the current events concerning the upcoming internationally renowned art event, I can say

it is raising a very interesting discussion in the art métier, concerning the purpose of the art movement being exhibited

in the leading galleries and museums today.

Are the directors of the event, Ivo Mesquita, and formerly Marcio Doctors, visionaries or just saving money??

Is what they are proposing a paradigm shift, or merely a consequence of financial mismanagement of the previous editions?

All these questions are arising and it seems appropriate to analyze carefully the issues involved.

The general public for art seems to be applauding the decision. After all, what is the sense of expending several million

dollars on an exhibition that plays no role in the present age in a country and planet filled with hunger and poverty?

It makes all the sense to exhibit the emptied Pavilion….

Several discussions and complaints are coming from the Art Market, arguing that there is no reason to cut it, as they are

commercially interested in the maintenance of this internationally very well respected institution.

The sincerity of the intention of Ivo Mesquita’s intention in organizing a Biennale with no works of Art in the 2nd

floor of the Pavillion is being overshadowed by critique, but it should be respected and praised.

This could be a turning point at the end of a decade of incomprehensible, nonsensical, and foolish installations that will

bring back some meaning and the essence of art.

Christina Roiter

Rio de Janeiro

February 2, 2008

|

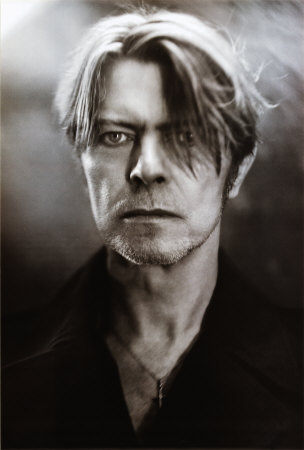

| David Bowie |

The History of Rock Music in the 1970s,

Or, Whatever Happened to Glam?

by Philip Auslander

The story rock historians tell about how the 1960s turned into the 1970s typically goes something like this:

The 1960s, which is to say the countercultural moment in rock, reached its apogee with the Woodstock Festival of August 1969,

and could only go downhill from there. This it did, rapidly: the Rolling Stones’ concert at the Altamont Freeway in

northern California a scant four months later, during which Hell’s Angels hired as security guards visited violence

upon the crowd, is often cited as decisive proof that the counterculture had imploded, destroyed by the dark forces that lurked

within it.

This description of the transition from the 1960s to the 1970s sets the stage for the next decisive moment in rock history:

the emergence of punk rock in 1975-6. Rock historians almost always describe punk as the antidote to everything that had gone

wrong with rock after the halcyon days of the 1960s. If stadium rock was too polished, standardized, and commercial, punk

was raw, immediate, idiosyncratic, and seemingly defiant of market standards, at least initially. Progressive rock, a form

that emerged in the late 1960s in the work of British groups like Yes and Jethro Tull and matured in the 1970s, embraced musical

complexity and instrumental virtuosity. It moved rock away from its roots in rhythm and blues, and proposed that rock was

“serious” (even “difficult”) music, music to be listened to, not danced to. Punk was hailed as a strong

reaction against the pretensions of progressive rock, a reaction that put rock back in touch with its origins in the rock

and roll of the 1950s and the bodies of its listeners. Or, in Robert Palmer’s pungent formulation, punk “save[d]

rock and roll from its big, bad, bloated self.”

As a way of questioning this valorization of punk as the definitive development in rock of the 1970s and the music that saved

rock from itself, I suggest that another rock subgenre has an equal claim to having reminded rock of the need for a backbeat,

powerful lyrics, and danceability. I am referring to glam rock, a primarily British phenomenon of the early- and mid-1970s.

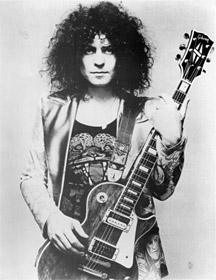

Typical practitioners of glam rock include Marc Bolan and T. Rex, and David Bowie. So powerful is the gravitational pull of

punk within the history of rock that when glam is mentioned at all in histories of rock, which it frequently isn’t,

it is as a precursor to punk.

|

| Marc Bolan of T. Rex. |

A partisan view of glam rock, however, suggests that it is as plausible a candidate

as punk to be the genre that “sav[ed] rock from its big, bad, bloated self” by reminding it of its origins. Jim

Farber argues, “Even those resistant to the larger glitter trend couldn’t deny its role as the era’s cutting-edge

sound. A sound with a retro appeal, glam gave rock & roll its balls back. While the previous psychedelic trend encouraged

decadent solos and haughty musicianship, glam revived the hard, mean chords of Chuck Berry and the Rolling Stones in the Fifties

to mid-Sixties.” In other words, Farber’s claims for glam are virtually identical with those Palmer makes for

punk. Glam can be seen as a reaction to the previous psychedelic and progressive rock trends that expressed the antagonism

toward the counterculture that would later typify punk. Like punk, it was aggressive, muscular music based in the fundamentals

of rock that looked back to the rock and roll of the 1950s. Glam rock was highly danceable, to the degree that Bolan and Bowie

even found themselves flirting with disco in the later parts of their respective careers as glam rockers. Most glam rockers

partook of an in-your-face attitude and some practitioners of glam, including Bowie and the New York Dolls, certainly produced

tough, hard-hitting lyrics. Inasmuch as glam came about before punk, it should have the prior claim to salvaging rock. So,

why is punk valorized as the defining development in rock music during the 1970s and glam relegated to the marginal status

of precursor to the defining development in rock music during the 1970s?

I suggest the reason rock historians valorize punk and deemphasize glam is that the history of rock is not independent of

rock culture but embedded within rock culture and reflective of its ideology. As Susan Douglas writes, “Real rock and

roll must be ‘authentic’—meaning it features . . . original songwriting, social criticism, a stance of anger

and/or alienation.” The concept of rock authenticity is linked with the romantic bent of rock culture, in which rock

music is imagined to be truly expressive of the artists’ souls and psyches, and as necessarily politically and culturally

oppositional.

Glam fulfills most of these requirements. Glam rockers took up a stance of alienation (Bowie’s portrayal of himself

as the extraterrestrial Ziggy Stardust suggests alienation from humanity itself). Male glam rockers wore make-up, dresses,

and effeminate fashions; their queer versions of masculinity were presented as an aggressive questioning of social gender

definitions. Glam’s failure to qualify as authentic rock results neither from its musical characteristics, its social

placement, nor its politics. It rests entirely on a question of performance: the relationship of the musician’s performance

persona to what is assumed to be the musician’s real self. Rock ideology insists that the musician’s performance

persona and true self be presented and perceived as identical--it must be possible to see the musician’s songs and performances

as authentic manifestations of his or her individuality. (I hasten to emphasize the words presented and perceived--it is not

the case that the rock musician’s performance persona and self must really be identical, only that a credible illusion

of identity is created and maintained.) Glam rockers specifically refused this equation, foregrounding instead the constructedness

of their performance personae. This is particularly true for Bowie, whose systematic and self-conscious metamorphoses of persona

(including his sexuality) and musical style represent a significant departure from the ideology of authenticity. Bowie’s

transformations were radical, frequent, and extreme: from the boy in the dress on the cover of The Man Who Sold the World

to Ziggy Stardust to Aladdin Sane to the Thin White Duke and beyond. More important than his particular transformations was

his implicit assertion of the conventionality and artificiality of all of his performance personae.

|

| KISS |

Glam rockers like Bolan and Bowie, each of whom crafted a distinctive and easily identified

body of music, were certainly rock auteurs. But by insisting that the figure performing the music was fabricated from make-up,

costume, and pose, all of which were subject to change at any moment, glam rockers undermined the authenticity of their performing

identities. The use of make-up in glam often asserted the artificiality of the mask rather than the authenticity of the person

beneath it. The members of KISS, for instance, performed in Kabuki-style make-up that completely masked their features and

turned them into types rather than individuals, each type defined by a certain make-up and costume, a certain pose and attitude,

and a certain set of stage rituals (e.g., Gene Simmons’ tongue-wagging and fire-breathing). It is glam rock’s

overt flirtation with theatricality and inauthenticity that makes it impossible for historians whose work implicitly reflects

rock ideology to entertain the possibility that glam was more than a footnote to punk, despite its legitimate claim to having

brought rock back to its musical roots and a stance of social opposition well before punk.

Rock historians’ insistence that punk restored rock to its proper project entails certain narrative contortions, however.

It is far easier to make a convincing case that punk purveyed socially critical lyrics and political consciousness by reference

to British punk rather than the slightly earlier phenomenon of American punk. American punk, as practiced by Television and

the Ramones, for instance, was far more self-conscious and aestheticizing than it was political. As Alain Dister points out,

many of the punk groups inhabiting the downtown New York scene of the mid-1970s defined themselves in terms of an interest

in modern French poetry: “Patti Smith and Richard Hell [of Television] citing Rimbaud, Tom Miller [also of Television]

renaming himself Verlaine. . . .” The Ramones are a particularly difficult case to assimilate to the argument that punk

was socially engaged. Musically, their stripped down, rough, and violent sound was indeed a return to rock at its most elemental,

and a harsh rejoinder to the meanderings of psychedelic rock and the classical aspirations of progressive rock. But the Ramones

also seemed to take pride in writing songs whose lyrics had no redeeming social content whatsoever. Furthermore, their practices

of having all band members adopt the surname Ramone, and look as much as possible like one another, suggested a level of self-conscious

irony closer to glam’s self-deconstruction than to rock authenticity.

|

| Sha Na Na in 1969. |

Such connections between glam and punk shed fresh light on another phenomenon frequently

omitted from the rock history books: Sha Na Na’s anomalous but premonitory performance at Woodstock. The surprising

appearance of a group celebrating the rock and roll of the 1950s at the heart of the 1960s counterculture can now be read

as presaging the rebellion against the music of that counterculture and the return to a pre-1960s sense of what rock is evident

in both glam and punk, as well as in the music of other 50s revivalists like the Stray Cats and Robert Gordon, who emerged

from and were embraced by the punk/new wave music scene. Sha Na Na ended many of their performances (though not, as far as

I know, their Woodstock appearance) by striking a pose of aggression against the counterculture. The live side of their 1971

album Sha Na Na (which is dressed in its own gold lamé inner sleeve, by the way) chronicles such a moment, as a member

of the group declaims: “We gots just one thing to say to you fuckin’ hippies. And that is that rock and roll is

here to stay.” The gesture is understood as an affectionate one, and the Columbia University crowd cheers. But for all

of its intentional inauthenticity, that moment anticipates the antagonism toward the counterculture that would be expressed,

in equally stageworthy but much less affectionate ways, in punk (e.g, in Johnny Rotten’s famous, home-made “I

hate Pink Floyd” t-shirt).

In addition to prefiguring punk’s desire to return to a pre-1960s version of rock, Sha Na Na anticipated glam. Their

costumes--including black leather “greaser” outfits and gold lamé Elvis suits--and preening stage poses were as

self-consciously constructed as any of Bowie’s identities. Bowie, Bolan, and other glam rockers troubled conventional

notions of male gender identity by embodying a fey androgyny undergirded by heterosexual machismo. As a group, Sha Na Na presented

a catalogue of similarly ambiguous masculine gender stereotypes as refracted through rock and roll and 1950s fashions. Those

in the group who embraced the “greaser” pose embodied masculine bravado and aggression, but also a preoccupation

with grooming (“grease”) and the moment-by-moment condition of their hair, addressed by the frequent application

of pocket combs. Like Elvis himself, the gold-suited members of Sha Na Na juxtaposed an almost feminine version of male beauty

with masculine sexual aggression. The distance from the male types represented by Sha Na Na and those staged some years later

and in a completely different musical context by the Village People is not as great as it may initially seem, and the connective

tissue between them is surely provided by glam rock.

Philip Auslander is the author of Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music. He teaches performance

studies at Georgia Tech.

www.philipauslander.com

|

|

|