|

|

|

| Robert Motherwell, Red 8-11, acquatint, 1972. |

Introduction

by Deanna Sirlin Editor-in-Chief The Art Section

The Spanish poet Rafael Alberti, in the middle of the last century, writes “A La Pintura” (“To Painting”)

dedicated to his friend Picasso after going to the Prado. In 1972 Robert Motherwell creates an artist’s book with aquatint

images and letterpress texts after he finds these poems and is moved by them. In 2007 Jane Rigler performs a piece with flute

and electronics and interactive video engineering that she has composed after being inspired by both poems and prints. The

butterfly effect continues, as H. Cecilia Suhr writes about this performance for The Art Section.

In these days at the beginning of this century it is a pleasure for me to present Phil Auslander’s interview with video

artist Paul Pfeiffer. Pfeiffer has made work referencing Freddie Mercury, Michael Jackson, and various sports figures; these

are his Prado. Media artist Daniele Roney found the most interesting work at Art Basel Miami 07 to be in the exhibition Thermostat:

Video and the Pacific Northwest, which she has written about for us here. I wonder how thinking about these diverse works

and discussions will influence my thoughts in the year to come.

Happy New Year !

www.deannasirlin.com

|

| To Painting at The Arts Center of the Capital Region, Troy, NY, April 2007. |

|

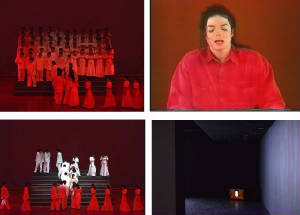

| Paul Pfeiffer, Live From Neverland, Video Installation, 2007. Courtesy: The Project. |

An Interview with Paul Pfeiffer

by Philip Auslander

New York-based artist Paul Pfeiffer has been described by Roberta Smith of The New York Times as "a

consummate digital/video craftsman." This is an excerpt from a longer interview to be published in a catalog by the University

of Georgia in the spring.

Since we’re focusing on your most

recent work, how would you say it relates to your earlier work? Are there

identifiable trajectories you feel yourself to be following?

The earlier and the more recent work are closely related in

many ways. I’m still working with time-based media; still sampling images from

television; and still thinking of ways to use those images to form a language

of my own.

How about in relation to your use of sound, specifically?

It seems to me that sound has become a more obviously compositional element in

some of your recent work.

Moving into sound seems natural after working with moving

images. The process of layering, juxtaposing, and sequencing video images has

always seemed formally related to musical composition.

From my earliest experiments with video and photography I’ve

been playing with the human figure and this continues in my experiments with

sound, which are all so far to do with the human voice. My first forays into

the use of video soundtracks were collaborations with sound artist Chris Kubick

a.k.a. Language Removal Services a few years back. Two video installations in

particular – “The Long Count (Thrilla In Manila)” and “Sex Machine” [both 2001]

– incorporate sound compositions made by Kubick. In both cases audio

recordings of celebrities being interviewed were re-edited, erasing all the

spoken words while leaving intact the uncanny breathing sounds and guttural

artifacts in between the words.

In more recent installations like “Live From Neverland” [2006] I’m

playing with another evocation of the human voice: the booming sounds of

crowds. In “Live From Neverland” 80 men and women recite in perfect unison a

statement by Michael Jackson that was originally broadcast on TV in 1982. The

sound they produce is halfway between an individual speaking voice and the roar

of a crowd.

You seem to have been very influenced by Guy Debord’s Society

of the Spectacle and the ideological

implications of the visual in a media-saturated culture. In a conversation with

John Baldesari published in the catalog for your 2003 retrospective, you say, “In today’s branded landscape, images

and

identities are pretty much synonymous. For me, the strategy of erasure is a

response to that situation.” How does this analysis apply to sound? Are sounds

as “branded” as visual images? Do you think of some of your manipulations of

sound as analogous to the erasure of images? Can the manipulation of sound in

multimedia work serve a similar critical purpose?

When it comes to making art, I think of image and sound as

part of the same raw source material. There are of course technical differences

between them but in my way of thinking and working they’re not simply

analogous, they’re largely the same. In a way, I think the real material to be

shaped is the perspective of the viewer. Images and sounds only have meaning

because they resonate with what’s already in people’s heads.

As for my take on media culture, when I’m in the studio I’m

not really thinking in terms of critical strategies or critical purposes per

se. I believe art making happens best when theory takes a back seat and a more

intuitive approach is adopted. What I’m thinking about mainly when I’m at work

is how slippery the process of signification can be. I spend a lot of time

thinking about the play of forms and meaning that’s activated in the process of

reframing found images and other materials. The creative process for me is all

about finding just the right way to structure these materials so that they

speak for themselves in some new way.

As someone who is interested in

performance, I’m fascinated by what I see in your work as gestures of

symbolically severing the relationship between a performer and his audience and

reconstituting it in other terms. I’m thinking about both the "Study for

Jerusalem" [2006] and "Live from Neverland."

In the former, Freddie Mercury’s

“call” has been detached from his original audience’s

“response” and, as I understand it, another audience was assembled to respond

to the recorded call. This is mirrored in the way the three parts of the piece

call out and respond to one another. One of the main things this brings to my

mind is the relationship of recorded sound to the audience. We consume music

mostly in the form of recordings, which means that we’re primarily responding

to music that was made at other times and other places than when and where we

actually experience them. In a sense, our “response” is always divorced

temporally and spatially from the musical “call” that initiates it. Even when

we go to concerts, arguably we are modeling our expectations and behavior

primarily on what we’ve seen and heard on recordings.

Your description of the distance

between a recorded performance and its reception by a living listener is very

suggestive. Expanding this further, wouldn’t you say that every communicative

act entails a distance or gap between a source and receiver? I don’t mean just

a literal distance in time and space or the literal mediation of digital

recording technologies. I’m referring to a more fundamental gap inherent to language.

There’s no way to guarantee a universal interpretation or understanding of the

meaning of things, nor would life be very interesting if you could. The most

profound aspects of human experience are by nature complex, multi-dimensional,

full of contradiction and paradox. For me the motivation to make art comes from

a desire to connect with others on this deeper level. As I see it art making

has less to do with self-expression and more to do the mediation of shared

meaning. You could even say it’s a kind of “call and response” with the viewer.

The most I can hope for as an artist is to come up with a picture that’s

convincing enough to compel viewers to complete the meaning for themselves.

The performer/audience relationship in "Live from Neverland"

is different. When on television, Jackson was addressing what was for him a

virtual audience. You have made that audience concrete, in the form of

something that looks like a gospel choir, yet you have also made that audience

speak Jackson’s words both back to him and for him. Again, there’s play with

temporal and spatial separations and gaps. And I wonder what you might be

saying about the relationship between performer and audience through this

depiction. Does this relate back to the ideas of branding and spectacle, images

and identities? Are the temporal and spatial discontinuities and

re-continuities you introduce into these scenarios meant to disrupt, or at

least drive a wedge, into the way image, identity, and brand become synonymous

in a celebrity driven commodity culture?

While I’m drawn to the use of images that are universally

familiar, like the image of Michael Jackson or of sports heroes, my interest is

not so much the famous personalities themselves but the aura that surrounds

them. I’m looking for ways to intensify that aura, to bring it into the

foreground and make it the focal point of the image. All the methods I use to

alter figures in my work – erasing, refracting, mirroring, looping, etc.

– are intended to work toward this end. In the case of Live From

Neverland, the elimination of Jackson’s voice, the recreation of his words by a

chorus, the re-syncing of Jackson’s mouth to match the chorus’ inflection: none

of this is intended to make a specific statement about Jackson himself, nor

about performers and audiences, or commodity culture in general. To me it’s

just another variation of the play between figure and background, subject and

context, that’s always been a central theme in my work. It’s my hope that when

the right balance is struck in this regard the picture becomes a kind of matrix

– a space in which a whole range of different suggestions of meaning can

coexist.

Philip Auslander teaches Performance

Studies in the School of Literature, Communication, and Culture at Georgia Tech.

www.lcc.gatech.edu/~auslander

For more information on Paul Pfeiffer visit The Project Gallery.

To see a video of To Painting, as performed at The Arts Center of the Capital Region in Troy, New York, click on the

image above. Video courtesy of Bart Bridger Woodstrup and the iEAR Residency Program at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Windows users may need to download Quicktime for Windows here.

Music With A View:

To Painting by Jane Rigler and Bart Bridger Woodstrup

(Flea Theater, New York City, April 9, 2007)

by H. Cecilia Suhr

To Painting

refers to the poems “A la pintura” written between 1947 and 1967 by the Spanish poet and painter Rafael Alberti.

These poems inspired paintings by Robert Motherwell that served as a stimulus for flutist and composer Jane Rigler, who states that “the intention of [her] work To Painting is to pay

homage to all that art (from [her] past) that inspired [her] to be a musician/artist of [her] own.” Rigler’s

performance thus encompassed two other artists’ visions and inspirations as they intersected with each other’s

and her own. As Rigler told me by email, the poetic muse of Rafael Alberti inspired Robert Motherwell’s vision, and

his vision inspired Rigler’s sound:

I looked at the paintings and read the poems for months before any performance images came to my own head. Once

I started working with Bart [who provided interactive visuals], I had, by then, already had a pretty good idea of what I wanted.

I could see separate movements each one with their own specific interactions, movement, colors, spaces, magnifying parts

of the works and such. It all came to be rather quickly.

Rigler’s account of the way in which visual elements affect her music is noteworthy:

the visuals are like a score. I choose parts of it to “follow,” I obtain the feel of the work and

I use the work to generate sounds by imagining what sounds are the best ones to emulate that color, texture, mood, rhythm,

etc.

While Rigler’s process does not focus on bodily movement or on the improvisational drawing patterns of a painter, it

does involve imagination. She uses the paintings as concrete guidelines (scores), but these scores do not determine directly

what she plays. Rather, they serve as as starting points for her own aural imagination.

Rigler’s imagination requires a longer duration than that connected with immediate interpretation or interaction with

an improvisational painter or musician. Rigler’s collaboration with Bart Bridger Woodstrup was carried out not as pure improvisation but, rather, as “an open form composition, incorporating elements of improvisation”

(Rigler). Therefore mediation, rather than immediacy, seems to have been the major issue. However, mediation here does not

necessarily mean computer electronics or the paintings; instead, it relates to the interweaving of the music with the myriad

paintings and poems. Even though Rigler “emulates” the works of art, this emulation is not simply a thin interpretation

of art, as she finds multifarious connections with life through the paintings and poems.

My intention is not necessarily to abstract parts of the art or the poems but to see them from various perspectives,

vantage points. To get inside the painting. To see the poetry. To hear both from another angle, sound, place from which

one can experience the life around us.

For Rigler, aesthetic experience does not always occur in a lofty place (e.g., heightened perception or consciousness), but

can happen within our own surroundings.

Sitting at a laptop computer, Woodstrup showed six slides of Motherwell’s paintings. As an audience member, I was unable

to discern what exactly Woodstrup was doing during the performance. When I asked him about his role, he responded, via email:

The only movement that requires me to improvise to the sound is the fourth movement, which depending on the speed

at which Jane is performing, I adjust the rate the images are flashing on the screen. This creates a call and response effect

between the images and music.

According to Woodstrup, even though the electronic manipulation of

the visuals by the sound is minimal, there is an interactive element

in the visual display, as differentiated from a "normal" slide show.

Woodstrup explained that the use of computer or video technology may

change or enhance the performance as a whole:

[It can] transform the space that the piece is being performed in. For example, Jane intended for the video projection

to immerse the space with the imagery of Motherwell's paintings. The scale of the paintings, the amount of light and color,

has an important aesthetic effect.

Woodstrup also added that while the real paintings may be interesting to perform to for a musician, the slides Woodstrup and

Rigler used could “match the immersive qualities of sound.”

In my experience as an audience member, not only did the slides incorporate movement into the performance, they also, as Rigler

intended, “immersed the space with the imagery of Motherwell’s paintings.” The images in the slides not

only moved, but also expanded and diminished as the zoomed in and out. Together, sound and vision created a unique aura akin

to the establishment of a virtual reality in the performance space.

Despite Woodstrup's feeling that this performance entailed only a

small amount of visual manipulation by sound, Rigler's performance

revealed how interaction with electronic instruments may differ from

that with acoustic instruments. Rigler pointed out that when she

performs with electronic instruments, she has an additional aspect to

consider; nevertheless, the effect she wants is the dissemination of

oneness:

With electronics, I have two instruments to think about at once. It is complicated but once I am playing, I recognize

that the end result is really only ONE instrument, and that is the effect I want. I want to create a hybrid voice.

As an audience member, I experienced this voice as a mysterious mixture of acoustic sound and electronic—the boundaries

between the two blurred.

Finally, in regards to the interaction between audience and the performer, I received a different response from each collaborator.

Woodstrup stated that the audience’s presence had no significant impact on his performance:

For this piece we were presenting abstract art and thus, were not directly communicating specific ideas. Such

open communication doesn't require a dialog with the audience that would affect my presentation.

While Woodstrup’s role may not have been affected by the presence of an audience, it was different for Rigler:

Audience always has an effect on my performance. I feel them too, and can tell when they are with me or not.

I depend on that...and have sometimes changed what I'm doing on the spot when I felt things weren't working for them...or

gone into more "risky" places when I feel they are willing to accept that. . . .

Rigler incorporates audience response into her performance by gauging the audience’s reception and responding to it

during the performance. Rigler’s musical influences come not only from the paintings and poetry but also from her attempt

to explore multiple perspectives of life, thereby not isolating aesthetics to the realm of “the other.” On this

note, I wonder, at what moment, do the performers feel the presence? Is it in the experience of awareness, or is it in the

meditative state of mind? Is it a direct bodily touch, or is it the connection to everyday life? I pondered upon these issues

as I left the performance.

H. Cecilia Suhr is a Ph.D. Candidate at Rutgers University (in media

studies), and also a musician.

www.ceciliasuhr.com

|

| Jeremy Shaw, 7 Minutes, Video, 1995/2005. |

Locational Identity:

Thermostat: Video and the Pacific Northwest at Art Basel, Miami

by Danielle Roney

As numerous international market segments attempted to identify themselves clearly in the sea of art fairs at Art Basel 2007

in Miami, Michael Darling, Jon and Mary Shirley Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Seattle Art Museum, sought to

provide his region with a distinctive identity through the survey exhibition Thermostat: Video and the Pacific Northwest,

part of the official Video Lounge programming at the Convention Center.

As local identity structures in society struggle to adjust to the continued growth of a global perspective, contemporary art

reflects upon the quandaries of balance between pluralistic, international experiences and local/regionalism in the United

States. How can work that reflects a regional sensibility draw attention in the trendy shopping mall marketplace of international

art brokers engulfed by the commodity wave?

Darling addressed this question by focusing on the strengths of the regional traditions of early super 8mm filmmaking, and

its historically rich musical counterpart, with sensitivity and well-balanced sentimentality.

It is interesting to note how the landscape itself tied together the self-defined regional classification, Cascadia, after

the Cascade mountain range, which includes continual interaction between many of these artists beyond their city limits and

country borders from Vancouver and British Columbia through migrations into California.

Exemplifying borderless environmentalism, Portland artist Vanessa Renwick’s Portrait #2: Trojan, from the Portrait

Series of Cascadia, documents the demolition of a looming, abandoned nuclear power plant tower juxtaposed with the serene,

exquisite landscape of the northwest forests and lakes. Shot in beautifully oversaturated 35mm, the experience transcends

while referencing regional history and storytelling through the bluegrass music accompaniment by Quasi’s Sam Coomes.

An additional work directly entwining these aspects is Kevin Schmidt’s Long Beach Led Zep, a self-portrait of

the artist playing “Stairway to Heaven” badly on the guitar on the Pacific coastline.

|

| Kevin Schmidt, Long Beach Led Zep, Video, 2002. |

As the program progresses into layers of urban interactions, examining intimacy and the masses, the public becomes the performer

in several documentary manipulations. Accomplished filmmaker/performer Miranda July, whose additional “Sampler”

program on Friday included Atlanta, an Olympic portrait from 1996, examined the personal, spatial and energy relationships

between two families sitting at the airport in her piece, Haysha Royko. The locked-down camera view incorporated an

animated color overlay for each person, positioning and repositioning the negative space of the empty seat between them. The

entertaining dilemma of an overactive and overtly oblivious child breaks all the barriers in a refreshingly simple portrait

of boundaries in common space.

|

| Miranda July, Haysha Royko, Video, 2003. |

Spatial and personal boundaries are also at issue in Vancouver artist Jeremy Shaw’s 7 Minutes, centered on an

underground subculture and teen violence. This revisited footage from a 1995 party with Jeremy’s skater and rave friends,

positions the viewer as voyeur in the hazy, slow motion account of a girl fight. Jeremy utilizes conventions of anticipation

and reality TV to examine the derivatives of anarchy, adolescence, and the continual geographical tensions of Vancouver’s

fault line earthquake threats. Coming from Los Angeles, I can attest to the deep pervasive impact of the threats surrounding

the region.

In contrast to the intimacy of the interior experience in Shaw’s piece, Roy Arden takes reality TV on a different journey

in Supernatural, a compilation of archival news footage surrounding a hockey riot in the streets of Vancouver. Resulting

from his background in urban photography and the found object, the clips becomes objects of time separated by a breathing

pattern of blackness, causing the viewer’s mind to extrapolate on each missing moment in their own imagination. Fragments

of action defy the traditional timeline as the depiction escalates and subsides in waves of violence and frivolity.

These inquiries provide an interesting reflection upon Joseph Beuys’s socialist perspective, as expressed in his 1973

essay “I Am Searching For Field Character”: “Only art is capable of dismantling the repressive effects of

a senile social system that continues to totter along the deathline: to dismantle in order to build A SOCIAL ORGANISM AS A

WORK OF ART” and Jean-Luc Nancy’s later communistic approach to the individual as the atomic result of the “dissolution

of the community” and an “abstract result of a decomposition” (The Inoperative Community, 1986).

Within the context of the Information Age and an ongoing redistribution of wealth worldwide, we must question the physical

and virtual relationships of the individual to the masses, and the struggle to redefine the social role of the artist and

art itself. Can the whole and its parts be emphasized in a symbiotic view globally or artistically? Sensitivity to the complexity

of this balance is critical to facilitate global cultural diplomacy.

Danielle Roney is a multimedia artist based in Atlanta, Georgia, USA.

www.danielleroney.com

www.globalportals.org

|

|

|