|

|

|

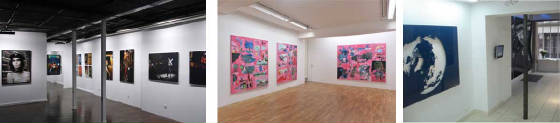

| School Gallery, courtyard on Rue du Temple, Paris, France. |

Introduction

By

Philip Auslander

Editor

The Art Section

Welcome to spring--it's becoming quite green and beautiful around us--and to the March issue of TAS!

For me, the contributions to this issue all concern the power of art and the force it exerts in our lives. Anna Leung's essay

on the Italian Futurists, inspired by a visit to the Futurism 100! exhibition at the Estorick Collection in London, reminds

us that there was a time when people believed fervently that art could wield real social and political power, that aesthetic

innovation was an essential companion to social change--perhaps, even, that aesthetic innovation could bring about social

change. This desire led the Futurists into an unfortunate alliance with Fascism; as Anna points out, however, the congruences

between Futurism and Fascism have been overstated. And the desire to believe that art can exert direct, instrumental power

in the social and political spheres persists.

We are pleased to offer a selection of poems from the Washington, D.C. based Francis Raven. These poems suggest the ability

of works of art to hold captive our attention, perception, imagination, and thought: they trace what happens in our minds

when looking at art, the associations we make when seeing paintings that are at a historical remove from us, the ways we both

connect them to our own experiences and oblige them to remain at a distance. Raven also evokes our sense as viewers of the

art-making process that must have led to the image we see, yet remains elusive.

Finally, Editor-in-Chief Deanna Sirlin brings us up to date on developments on the Paris art scene through an account of some

young galleries she visited there and an interview she conducted with three gallerists whose spaces are new to that scene.

Each gallerist evinces a strong desire that the gallery not be just a store for art, that it be the locus of a community constituted

by gallerists, artists, viewers, critics, and others. Optimally, this community should hold the art work at its center--the

art is its reason for being. The passionate commitment to art and artists that led these three people to set up galleries

in a highly competitive environment during difficult economic times is palpable in their words (which we present here both

in English translation and the original French).

All my best,

Phil

www.philipauslander.com

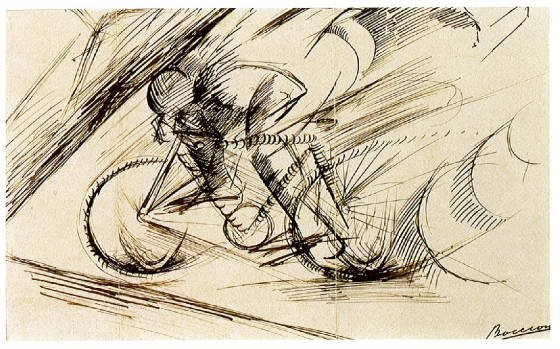

Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916). Dinamismo di un ciclista [Dynamism of a cyclist]

(1913).

Courtesy of the Estorick Collection, London, UK.

Futurism 100!

At the Estorick Collection

by Anna Leung

Except in struggle there is no beauty. No work without an aggressive character can be a masterpiece. Poetry must

be conceived as a violent attack on unknown forces, to reduce them and prostrate them before man.

We will glorify war – the world’s only hygiene – militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers,

beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn of women.

Art, in fact, can be nothing but violence, cruelty and injustice.

--F. T. Marinetti, The Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism, February 1909

It is exactly a hundred years since Marinetti’s Foundation and Manifesto of Futurism was published on the front

page, then the arts page, of the Paris newspaper Le Figaro. Though obviously targeting the Italian ex patriot intellectuals

and artists who had been drawn to Paris in the first decade of the century, it was also aimed at the Parisian intelligentsia.

Publishing the Manifesto in Paris gave it instant avant-garde credibility. Although the Manifesto was Italian in provenance

and orientation, this extraordinary editorial coup proclaimed its international status, thus ensuring that Futurism was taken

seriously and not rejected out of hand as a provincial movement. (The Manifesto was in fact published simultaneously in Italian

in Poesia, a literary magazine but significantly was also printed in broadsheet form and sent to well known public

figures all over Italy. Marinetti is said to have received more than ten thousand letters in response to this publication,

many positive.)

The manner in which Marinetti proposes the main elements of a Futurist aesthetic, and the way he perceives the role of the

artist and the function of art within society, have lost none of their capacity to shock. Futurism dealt a double blow to

the art world; it was aimed principally at the complacency of the Bourgeoisie but, as the first of the self-consciously avant-garde

movements to emerge in the course of the 20th century, it dealt an equally vicious blow not just to the art institution but

to the avant-garde per se. However, unlike Dada, which borrowed many of its ideas and techniques from the Futurists, including

their bruitism (noise performances that were likely to include all manner of noise makers), nonsense syllabic poetry and provocative

performances, Futurism was not explicitly anti-art. Rather, it was for an art which was no longer clogged up with symbolist

nostalgia, an art which looked not back to the past for reassurance but ostentatiously to the future. Tradition had to be

ruthlessly extirpated - it had held Italy back for too long, making it a cultural backwater of Europe. Futurism presented

itself, therefore, as a challenge to academism and its outmoded cultural values, based for far too long on the dead weight

of the Italian Renaissance, but it was also a xenophobic project in praise of war and military adventurism with war celebrated

as the loudest most chaotic of all futurist performances. This is the link between Futurism and Fascism that this exhibition,

with its one room devoted to the Futurist Umberto Boccioni and another devoted to the contemporary Italian artist Luca Buvoli,

seeks to address.

The 19th century avant-garde had been seen as a leftist project. Its utopian credentials, whether associated with the Arts

and Crafts movement in England under Ruskin and Morris or with the anarchist movement in Paris with which Georges Seurat had

an association, were premised on the necessity for equality and justice for the workingman whose livelihood was endangered

by modernity and the tyranny of the machine. The Futurist artist, on the other hand, was to become an activist whose individual

future and whose country’s future were to be intimately bound up with the machine as the main agent of change that could

redress the political status of Italy. This was in fact no empty talk. For whereas Italy had lagged behind other industrial

nations in the first phase of the industrial revolution that was primarily coal based, and consequently suffered from a serious

inferiority complex in its inability to compete as an equal with the other industrialised countries, especially Germany which

like Italy had only just become a nation state, by the 1900’s it began to catch up with the second phase based on electricity

and the internal combustion engine. The development of hydro-electric power was especially important because of Italy’s

lack of coal. In the early 20th century, Italy effectively lived through two industrial revolutions at the same time, leading

to many cultural incongruities as the old established Italy was juxtaposed with the new pragmatic realities of the industrial

age.

For the Futurist artist, the machine was therefore the symbol neither of servitude, as in Britain, nor of rational design,

as it was in Germany, but rather of uncontainable vitality. The car was admirably suited to Marinetti’s aesthetic, a

romanticised vision of technology that celebrated man’s victory over Nature. Significantly, conversion and baptism into

this new religion of Futurism was recounted in the Manifesto in a highly stylised, theatrical narrative of an automobile accident

in which Marinetti and friends out on a midnight rampage were flung from their automobile into a “maternal ditch”.

Marinetti then proclaims, “when I came up – torn, filthy and stinking- from under the capsized car I felt the

white –hot iron of joy deliciously pass through my heart.” Futurism, as defined by the eleven-point program outlined

in the Manifesto that provided the theoretical basis for all aspects of Futurist art making, was born of that moment. As we

shall see when we focus on Boccioni, however, the theory far preceded actual art practice.

Central to the Manifesto was the creation of a new ideology that in Marinetti’s symbolist rhetoric was raised to the

level of a new post Nietzschean godless religion based on speed. Marinetti argued that speed, whose essence was the “the

intuitive synthesis of all forces in movement,” was by nature pure. Futurism effectively replaced the binary values

of good and evil with “a new good: speed, and a new evil; slowness.” This binary opposition should be kept in

mind when we come to Buvoli’s installation. Translating modernism into Bergsonian terms of dynamic change, speed comes

to incarnate the Absolute in this life by guaranteeing man’s, and an essentially masculinist, victory over time and

space. Pictorially as well as verbally what this first called for was the destruction of the autonomous art form, art for

art’s sake, upon which most modernism was based. In Futurist performances, the poem was enunciated with the maximum

of disturbance, becoming a parody of itself; in the pictorial arts, the composition was no longer a balanced composition but

a collage of events that entailed the loss of a dominant image just as in the poem what was lost was the authorial “I.”

A central ordering system was replaced in both cases by incidents, accidents and the possibilities of discourses, all of which

were not intrinsic to art but related to the life taking place around us. What is obliterated is the difference between the

real world and the pictorial or poetic field of activity. What is focused on is the coming into being of things and the importance

of improvisation. What results is the breakdown of all barriers and the fusion of the environment with the object and of the

subject with the world. There is an interesting remnant of romanticism here in the scattering of the self in the universe

and its resurrection in the creation of a super “I,” revealed to twentieth century consciousness in the image

of the fearless pilot in his heroic airplane, images that Luca Buvoli uses in his videos. These, however, are not the images

that we see in Boccioni’s drawings, which represent an earlier attempt to translate Futurist ideas. It is only gradually

and through the implementation of Cubist strategies that Futurist painters and sculptors were able to approach, and eventually

realise, Marinetti’s radical ideas.

Umberto Boccioni: Unique Forms

Umberto Boccioni (1882-1916) was born in Reggio Calabria. His father was a mining engineer

employed by the government, which meant that the family was continuously on the move during his childhood. From 1899, after

studying at local art schools, he moved to Rome where he met the painter Gino Severini and studied divisionism in Giacomo

Balla’s studio. In 1906, he left Rome for Paris and, in the summer of the same year, travelled to Russia, returning

to Italy by the end of the year, where he settled in Milan. It was here that Marinetti made contact with some of the painters

in Boccioni’s circle and, in February of 1910, they published a Manifesto of Futurist Painters. This manifesto,

probably edited by Marinetti, demanded a return to a tabula rasa in order to destroy the old conventions based on the cult

of the past and that painters give all their combined energies to “our day-to-day world, a world which is going to be

continually and splendidly transformed by victorious Science.” It ended with a vow to ‘make room for youth, for

violence, for daring.” Ironically Boccioni, who enlisted with the Lombard Volunteer Cyclist Battalion, which was disbanded

in 1915, died on the front in the following year having been thrown off his horse,

The drawings that make up Boccioni’s "unique forms" represent an attempt to create art works that do not merely reproduce

aspects of contemporary life but also demonstrate how seemingly solid objects are actually defined by the interplay between

solid mass and its environment. In Boccioni’s words: “We proclaim the absolute and complete abolition of definite

lines and closed sculpture: We break open the figure and enclose it in environment.” Boccioni’s images may at

first glance seem unambitious and overly dependent on Cubist syntax. Precisely because the whole concept of linear dynamics

as lines of force that interpenetrate all things, breaking down what was assumed to be solid corporeal mass, is so demanding,

especially when confined to 2D, Boccioni was wise to limit his first undertakings in the direction of a Futurist aesthetic

to the image of the human body. He was attempting to unite interior and exterior, past with present and future, the actual

and the remembered within a single image. Indeed in another series of paintings entitled collectively States of Mind,

Boccioni explored not just the interaction of solid mass and space but also the fusing of elements in interior landscapes

through the narrative of the train station and psychological and emotional responses to travel. In many ways, however, this

radical revision of what we see is in fact better served by sculpture whose solid forms could be opened in both active and

passive modes to simultaneously enclose and be penetrated by the environment. But even more radical and far seeing was Boccioni’s

realisation that traditional sculptural materials needed to be replaced by the introduction of common use materials such as

glass, metal, leather, mirrors, electric lights etc., a practice that he may well have appropriated from Vladimir Tatlin’s

relief sculptures, seen during his stay in Russia.

It is curious that despite his encouragement to radical artists to “only use very modern and up-to-date subjects in

order to arrive at the discovery of NEW PLASTIC IDEAS” Boccioni’s own sculptural works continued to be based on

such traditional genres as the human figure or still life object and were cast in bronze rather than making explicit use of

new materials (thought it is true that some of his more experimental works are lost). The two sculptures on show are very

forceful and far from merely representational. Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913), possibly derived from Rodin’s

The Walking Man (1877) but fired with a completely different sense of optimism and resolve, is based on the idea of

contending force fields that exert their impact on a body striding forward into space, while his still life Development

of a Bottle in Space (1912) is his first successful sculpture in the round.

In many ways, the post-Impressionist Italian sculptor Medardo Rosso (1858-1928), whose work can be seen in the Estorick’s

permanent collection, prefigured Futurist thinking on sculpture. He rejected the concept of sculpture as statuary and saw

it as the impact of space on mass; Boccioni acknowledged his debt to Rosso in the Technical Manifest of Futurist Sculpture.

The other great influence was, of course Picasso, especially his cubist heads. However, Boccioni’s own resolution to

the problem of capturing the way an object interacts with its environment is best understood in his still life Development

of a Bottle in Space. The sculpture is premised on an interplay between solid and void. The bottle in question, with its

core of emptiness, arises from a nest of volumes that can either represent the opening up of the object or its enclosure within

space. An object in the round, it presents different facets to each viewer, Boccioni giving us the illusion of the spiralling

form of the bottle expanding into space while trying to make space itself “palpable, systematic and plastic.”

Boccioni treats the space around the bottle as if it were a material substance made up of arabesque curves, so that form no

longer takes up space but is generated by it, and in so doing suggests the familiar shape of the bottle.

Luca Buvoli: Velocity Zero

Luca Buvoli’s (b. 1963) installation in Room 2 questions the relationship between

the aesthetic and the political in terms of our modern faith in technological progress. A mural painting dominates the gallery

space, pulsing with the energy of a very fast moving car, Marinetti’s preferred symbol of progress and modern beauty.

This issues from a Rodchenko inspired, larger than life sized drawn head speaking into a megaphone. The speeding car, which

threatens at any moment to jump off the surface of the wall, represents both power and loss of control, giving rise to a discourse

on the relationship between heroism, vulnerability, and masculinity and the way these are interrelated not just in Italian

history but globally when it comes to totalitarian and authoritarian regimes. This image, which stretches across the breadth

of the wall, is broken up by a series of propaganda posters and two videos that are equipped with headphones. A Very Beautiful

Day After Tomorrow is based on a saying that Marinetti passed on to his daughter Vittoria when the Fascist regime he still

supported was close to collapse.

The video, made up principally of an interview with Vittoria, is spliced through with a Fascist patriotic song, “The

Aviator’s Song,” sung by a children’s choir. The other video, Excerpts from Velocity Zero on the

opposing wall, is made up of excerpts from Marinetti’s 1909 Manifesto but read out by a group of American sufferers

from aphasia, a condition that affects speech patterns. In this way the bombastic self promoting rhetoric of the Manifesto

is rendered redundant, its triumphalist ideologies made slow and awkward so that they are compromised from within by this

performance of painfully laboured, weakly articulated theses that ostensibly celebrate speed and violence and promote the

contempt of women. The recorded voices are fragmented, as are the images of the speakers which are captured by fine line

drawings, filmed frame by frame, their indeterminacy underlining the basic aim of the Futurists to capture the intersection

of subject and the world in a seemingly never ending flux of lines that express their responses to the spoken word.

Afterthoughts

Patriotism and the cult of violence were not limited to the right wing in Italy. Politically,

both the revolutionary left wing syndicalists who were influenced by the writings of Sorel and right wing nationalists rejected

reformist Socialism and parliamentary democracy, and both factions supported the Italian claim to Libya to demonstrate to

the world Italy’s progression from nationhood to imperialist power. It was this same matrix of activist ideas based

on the primacy of Nietzschean affirmation and of intuition over reason and argument that enthused Marinetti’s Futurism.

As a group, the Futurists were trenchant in their support of Italy’s intervention in the First World War on the side

of Britain and France, seeing this as a continuation of their country’s unification. This hectoring call for military

glory anticipated Fascist ideology under Mussolini, modernization and patriotism becoming the two main articles of faith embraced

by the Futurists. Some qualifications are in order, however.

First, we should realize that it is all too easy to take Marinetti’s imagery of destruction and renewal too literally.

It is important to be aware that he was a poet, and that his language was metaphoric. His imagery of cities in a state of

febrile agitation defined not a political but an aesthetic coup d’état.

Second, Futurism was an avant-garde project that was not predominantly rightwing, despite Marinetti’s attempt to make

it into a political party in its own right and its subsequent entanglement with Mussolini. Mussolini originally co-opted it,

not despite, but because of its leftist leanings. Futurism was however, unquestionably nationalistic in its orientation, which

led to its engagement with proto-fascist ideologies that have caused much discomfort in the art world, where avant-garde movements

are axiomatically categorised as leftwing and internationalist in spirit. Futurism threatens to turn this alliance between

politics and aesthetics inside out.

Futurism 100! brings this paradox out into the open and asks us to consider the relationship between the self-aggrandisement

so characteristic of the Futurist artist and the subsequent proponents of Fascism, among whom Marinetti counted himself as

one of the most faithful, staying till the bitter end in Mussolini’s short lived republic of Salo. However, it would

be as simplistic to equate Fascism and Futurism, especially in the light of Futurism’s natural hostility to the discipline

and hierarchy demanded by the Fascist regime as well as its ever more restrictive bureaucracy, as it would be to see Futurism

as representing the Fascist state in terms of its artistic production, especially in the light of fascism’s emulation

of the past glory of Rome, which could not have been more at variance with its own futuristic dynamic. Complicity there was,

and affinities too. These continue to subsist in our own culture but more at a deeper cultural and even psychological level

than a specifically political substratum of ideas.

Text © Anna Leung, 2009.

The exhibition Futurism 100! runs from 14 January - 19 April 2009 at

the Estorick Collection of Modern Italian Art in London, UK.

Anna Leung is a London-based artist and educator now semi-retired from teaching at Birkbeck College but

taking occasional

informal groups to current art exhibitions.

|

|

|

|

|

How did you first get involved in contemporary art?

Olivier Castaing:

My vocation is inscribed in my family’s DNA: my paternal grandfather and great-grandfather were both

painters and, until

I was 18, I lived in the midst of their work, which covered the walls of our family home.

When I was young, I spent hours contemplating the gallery of family portraits painted by my grandfather,

his intimist scenes,

drawings, and preparatory studies.

With the first money I earned I bought myself paintings, then a great many sculptures, installations, photographs,

and also

design, especially lighting. My escapades in Brussels, Berlin, London, and New York were pretexts for shopping

for rare pieces

or pieces never seen in France. Each move was an opportunity to encounter new forms of art and new artists.

Alongside my job in communications and the Internet, which allowed me a lot of free time, I assiduously

frequented artists’

studios, galleries, and museums to enrich my knowledge and refine my eye and tastes.

Isabelle Gounoud:

My first contact with contemporary art goes back to the mid-1970s when I was a student, discovering the

theatre and film as

well as the first contemporary art biennials in Paris. My professors were art critics, art historians...

and artists. I remember

“Francis Bacon,” a stunning exhibition in 1971 in Paris, and Barnett Newman’s “zip”...

. I was

working at that time in the theatre, after having trained in France and in London. The theatre of that time

was a place of

experiences involving actors, dancers, writers, film directors, lighting designers... if you remember Bob

Wilson’s directing...

this was “contemporary art.” As well as Marguerite Duras, her novels, her films; Carolyn Carlson,

experimental

film directors, of course, but also Antonioni, Godard, Michael Powell... If you think of performance artists,

plastic artists,

musicians, video makers... they all participated in the contemporary art scene of the time.

Years later, when I was working in film and audiovisual production, I particularly remember the making of

a film on Eric Fischl

and Pierre Bonnard, during which I met one of Bonnard’s nephews, who gave me the opportunity to hold

in my hands some

of the artist’s diaries, whose pages contained his daily reports on the weather and sometimes little

sketches of his

wife... Intimacy, flesh, and light in Fischl’s and in Bonnard’s paintings. I’ve noticed

that I have difficulties

in dividing art and artists into “sections.” Of course there are different mediums, periods

etc., but the dialogue

among all of them is constant.

Loraine Baud:

A woman professor at the university helped me take my first steps into the world of contemporary art. I

discovered there a

new vocabulary, a way of addressing questions to which my more “classical” education didn’t

fully respond.

The concepts of position, of commitment, of performativity marked and transformed the manner in which I

looked, listened,

and understood the artistic field, the plastic arts and contemporary dance.

Why did you want to open a gallery?

Olivier Castaing:

For more than 15 years, I organized ephemeral exhibitions, usually

over a four-day weekend,

to help artists sell their work. These became regular events that served as pretexts for discovering unusual

locations in

Paris and new artists.

Nevertheless, this formula was limited by the short run of the exhibitions and the impossibility of working

in depth with

the press or institutions. It was difficult to exist in the contemporary art world with no real “legitimacy”

while

working without a fixed place and with a wide variety of artistic conceptions.

I have also worked as an exhibition organizer, having put together two events designed to revivify a Cistercian

abbey in central

Brittany, in the northwest of France. For these biannual events, I created a symposium of semi-monumental

sculptures and a

contemporary art biennial. These events continue today, having been taken up by local experts in the field

of contemporary

art.

As a freelance curator, I’ve organized photographic exhibitions about Paris, particularly for Swedish

artists, as well

as the inaugural exhibition that accompanied the opening of the Fondation Jean Rustin, a major French painter

who is now 80

years old.

In addition, I created and ran an art blog for 18 months, with an art historian. We alternated in writing

accounts of exhibitions,

studio visits, or texts about an artist, a work, or a specific period in the history of art.

Two years ago, I decided to bow to the inevitable and devote myself entirely to my passion for art. I only

had to find a spot

in the gallery district at the heart of the Marais, which has become the epicenter of contemporary art in

Paris, raise money,

put together a team of artists, and finally develop a program.

Isabelle Gounod:

I could speak about my lineage, the musicians, writers, painters,

actors, and poets

in my family... and about all those years working in various sectors of artistic production, theatre, film

and documentary

production, art therapy, and the collaborations with artists, actors, directors, photographers, and plastic

artists. They

certainly led me over the years to see that I couldn’t imagine taking on any role in life other than

that of supporting

artists and their work. I was an actress, and it seems to me that those years of working and thinking about

texts, writing,

actors, and “acting,” were essential and perhaps allow me a certain empathy with the artist

himself as well as

his artistic concept.

Loraine Baud:

It was a decision that seems to have been made for me. I’ve

always worked with

artists. As an agent, I searched for ways to carry their work. After numerous projects, I realized that

the gallery structure

offered the best way for me to sustain and diffuse it.

How would you describe your gallery and the artists you exhibit?

Olivier Castaing:

The School Gallery, which specializes in contemporary art, represents French

and foreign artists

in multiple disciplines.

My primary objective is to bring to light young artists or artists who are recognized in other countries

but have no real

visibility in France, like the Argentine artist Marie Orensanz, a major presence on the South American art

scene who is now

72 years old and to whom the Museum of Modern Art in Buenos Aires gave a spectacular retrospective in 2007.

My interest in the art scene in Argentina led me to devote my first vacation since opening the gallery to

an extended stay

in Bueno Aires, where I met at least 40 artists with the help of Orly Benzacar, director of the gallery

of the same name and

a prominent figure in the Latin American art world.

I am also motivated by a real desire to promote emerging artists while taking into account the diversity

of current artistic

practices and being careful not to specialize in any particular medium or domain.

It seems to me that eclecticism is a basic requirement for being on the lookout for new ideas and even for

sustaining the

interest of the audience, collectors, and institutions, and running a space devoted to art and exchange.

The gallery’s programming is plotted against three axes:

Socially “Committed” Projects, like the Water War group show in the spring of

2008 devoted to “wars

fought about water throughout the world,” or the book and exhibition Testimony, a photographic project

by the Swedish

artist Joakim Eneroth about the torture of Tibetan monks by the Chinese.

The choice of themes oriented toward social problems shows my willingness to promote artists who demonstrate

a “militant

humanism” with works that defend fundamental liberties, as in the gallery’s inaugural exhibition,

entitled “liberté

toujours!” (Ever Free) or the show that opened the second season, by the Argentine artist Marie Orensanz,

entitled “

. . . pour qui? . . . les honneurs . . . “ ( . . . for whom? . . . the honors . . /).

Exhibitions of photography or video. Almost half of the gallery artists use these media in their

work, though not exclusively,

since some are also painters or plastic artists.

Futuristic projects, incursions into the realm of design or architecture, monumental installations,

sound works, artistic

overviews.

This kind of exhibition allows me to bring in artists who aren’t under contract to the gallery but

whose artistic ideas

enrich its project nevertheless.

Isabelle Gounod:

I am incapable of describing something that is constantly evolving.

I’ve been

asked what determines the gallery’s direction: My choices! Above all else, it’s about encounters:

with an artist,

with a person, then with his artistic concept, and finally with his/their work(s).

Each artist is different. I love their urgency, a certain understanding of the world, a desperate yet saving

irony.

I retain from the theatre the spirit of the troupe, of dialogue among “actors.” If we work together,

if we “choose”

each other, which is how it happens, it may be in part because of what we recognize in each other, but we

go where the artists

take us. They are the leaders.

Loraine Baud:

The gallery is both an exhibition space and a platform for mediation.

I think of it

as an open space, a space of exchange. This induces in me an attitude toward both the artists with whom

I work in close collaboration

and the audience I welcome. With both audacity and humility, I ambitiously suggest a new way of seeing,

I defend contemporary

painting, and I promote embodied art.

How did you find the artists you represent?

Olivier Castaing:

I launched my program in 2008 with artists I already knew, either

because I had used

them in my biennial project or because I had given them an individual show during the time I was a freelance

curator.

This is the case for Naji Kamouche, who participated in the first Biennial of contemporary art at the Abbaye

de Bon Repos

(in Brittany, France); Joakim Eneroth, whom I met at Fotofest (in Houston, Texas, USA); or Susanna Hesselberg,

whom I’ve

known since her stint as an artist-in-residence at the Cite Internationale des Arts in Paris.

For me, choosing a gallery is like joining a family, and I value the opinions of all of its members. Even

though I make all

the final decisions, their views influence me significantly.

Isabelle Gounod:

I lived with a photographer and plastic artist, and met at that time other

artists with whom

I became friends, some of whom I continue to work with today, like Michaele Andrea Schatt, whom I met well

before I decided

to open a gallery. I had very much wanted to make a documentary on her work; it never got made, but years

later I asked her

if she would be willing to join a brand-new gallery in a suburb of Paris and we opened the first exhibition

together. A small

gallery, it was a bit like “the little shop on the corner”! Earlier, I had met Michel Alexis,

who lives and works

in New York and Paris, and he who also joined us presenting paintings “around” Gertrude Stein’s

diary...

One evening in winter, I received an e-mail from Jeremy Liron, a young student at the École des Beaux-Arts

in Paris. I discovered

his paintings, his writings—he was just starting out, and so was I!

Now that the gallery is in Paris, I get a great many solicitations from artists, which makes me appreciate

all the more those

who had confidence in me at the very beginning.

The little “troupe” has grown and welcomed other “actors,” but it’s all still

about the encounter

and desire for that encounter. This is the driving force, stimulating and infinitely subtle.

Loraine Baud:

They are the artists with whom I was already working and who gave me the desire

and courage to

open the gallery. It is they who instilled in me the desire to present their work, to accompany them.

What is your greatest challenge with the gallery?

Olivier Castaing:

It’s a question of knowing how to exist in the midst of the

more than 500 galleries

active in the Parisian art market.

How to emerge from the crowd, how to forge and maintain a distinctive identity and get enough attention

from the press, institutions,

and collectors for your programming and the artists you promote.

It is also an economic challenge, considering the high cost of rent, production costs, and the risks inherent

in the market.

I seek to distinguish my gallery by providing as much access as possible to the artists themselves, putting

artists back into

a system in which they all too often become “significant by their absence” to the point that

it almost becomes

a challenge to meet an artist at his own show! As an event, each exhibition is a pretext for organizing

encounters with the

goal of becoming a platform for ongoing exchanges and meetings between the artists and people from other

fields: writers,

psychiatrists and psychoanalysts, architects, landscape architects, teachers and researchers, and politicians

in the hope

of generating a true dynamic and stimulating debates with collectors, art lovers, and the general public.

Isabelle Gounod:

To last!

Loraine Baud:

To make it visible on the international scene.

What is your greatest challenge with your artists?

Olivier Castaing:

As for all galleries, supporting the artists involves producing the

work presented,

assisting in outside projects, particularly publications, and continually calling on art historians or critics

to write about

each exhibited project in order to contextualize the work.

Supporting the artists over time should be the objective that drives all gallery activities. This has to

do above all with

focusing energy on all of the operations involved in showing and valorizing the artists’ work in the

gallery, but also,

and importantly, in institutions and public or private collections.

The gallerist and artist must work side by side in a relationship that entails absolute confidence and true

osmosis to best

defend and sustain the work, and allow it to emerge from the studio under the best conditions possible.

For a young gallerist, this necessitates the creation of a network of active collectors who believe in the

gallery’s

choices and are able to contribute to the production of major projects, and the development of a network

of institutional

correspondents, journalists who are prepared to follow the work of the gallery artists.

It’s a daily marathon, a long-distance race that requires enthusiasm, energy, and, above all, passion

for artists and

their art.

Isabelle Gounod:

To reassure them. . . . Gallerists, commissioners, conservators, and critics

are all intermediaries--we

draw our energy from the relationship we have to art thanks to the artists. The challenge? The artists present

no challenge

other than to sustain them through time, to give them voice.

Loraine Baud:

To give them the opportunity to produce as freely as possible, and to pursue

our collaboration

for as long as possible, in a climate of respect, transparence, and confidence.

Deanna Sirlin is Editor-in-Chief

of The Art Section and an artist whose work can be seen at www.deannasirlin.com.

Comment

êtes-vous devenu la première fois impliqué dans l'art contemporain?

Olivier Castaing:

Mon projet s'inscrit assez logiquement dans l'ADN familial, avec

un grand père et

un arrière grand père paternels artistes peintres, ayant vécu jusqu’à l’âge de 18 ans au milieu

de leurs œuvres

couvrant les murs de la maison familiale.

Etant jeune, je passais des heures à contempler la galerie de portraits familiaux réalisés par mon grand

père, les scènes

intimistes, les dessins et études préparatoires.

Avec mes premiers salaires j’ai tout naturellement commencé à m’offrir des peintures puis de

très nombreuses sculptures,

des installations, de la photographie mais également du design et notamment des luminaires, mes escapades

à Bruxelles, Berlin,

Londres ou New York étant prétexte à chiner des pièces rares ou jamais vues en France. Chaque déplacement

devenait une opportunité

de rencontres avec de nouvelles formes d’art et de nouveaux artistes.

En parallèle de mon job dans la communication et l’internet, qui me laissait de nombreuses plages

de loisir, j’ai

assidûment fréquenté, ateliers d’artistes, galeries et musées, pour enrichir mes connaissances et

affiner mon œil

et mes goûts.

Isabelle Gounod:

Mon premier contact avec l’art contemporain remonte au milieu

des années 70,

j’étais alors étudiante et découvrais le théâtre, le cinéma et les premières biennales d’art

contemporain à Paris.

Mes professeurs étaient critiques d’art, historiens de l’art … et artistes.

Je me souviens d’une étonnante exposition en 1971 « Francis Bacon », de la découverte du « zip »

de Barnett Newmann…

J’ai ensuite rejoint le théâtre après des études de théâtre à Paris et à Londres. Le théâtre à cette

époque était un

lieu très expérimental, réunissant les acteurs, des danseurs, des auteurs, des réalisateurs, des régisseurs

lumière…

si l’on se souvient des mises en scènes de Bob Wilson… nous étions en présence de « performance

», d’ «

installations ». Il en est de même avec l’oeuvre de Marguerite Duras, si l’on pense à la rythmique

de son écriture,

au travail de la voix off sur l’image dans ses films, dans ses pièces… à la recherche de Carolyn

Carlson sur l’inscription

du corps dans l’espace, aux réalisateurs de films expérimentaux bien sûr, mais aussi à Antonioni,

Godard… Ils

ont tous participé à ce qui constitue la scène actuelle de « l’art contemporain ».

Des années plus tard alors que je travaillais dans le secteur de la production cinématographique et audiovisuelle,

je me souviens

tout particulièrement du tournage d’un documentaire sur Eric Fischl et Pierre Bonnard, au cours duquel

je rencontrais

l’un des neveux de Pierre Bonnard qui me donna l’occasion de tenir entre mes mains quelques

agendas de l’artiste

dans lesquels il reportait quotidiennement des annotations sur le temps, la lumière, et parfois des petits

croquis de sa femme...

L’intimité, la chair et … la lumière dans la peinture de Fischl comme dans celle de Bonnard.

Ce sont ces rencontres

et d’autres qui au fil des ans m’ont menées à l’ « art contemporain ».

Loraine Baud:

C'est une enseignante à l'université qui a accompagné mes premiers

pas dans l'art

contemporain. J'ai découvert un vocabulaire nouveau, en prise avec mes questionnements auxquels mon éducation

plus "classique"

ne répondait pas totalement. Les notions de posture, de parti-pris, de performativité ont marqué et transformé

la manière

dont je regardais, écoutais, comprenais le champ artistique, des arts plastiques à la danse contemporaine.

Pourquoi avez-vous voulu ouvrir une galerie?

Olivier Castaing:

Pendant plus de 15 ans j’ai organisé des expositions éphémères,

généralement

en fin de semaine sur 4 jours pour aider les artistes à vendre leurs œuvres. Ces rendez vous sont

devenues réguliers,

prétexte à découvrir des lieux insolites dans Paris et de nouveaux artistes.

Cette formule avait néanmoins des limites tant par le format court des expositions que par l’impossibilité

de faire

un travail de fond en presse et auprès des institutionnels, en l’absence de « légitimité » réelle,

sans lieu fixe et

avec une grande variété de propositions artistiques, difficile d’exister dans le milieu de l’art

contemporain.

J’ai également fait du commissariat d’exposition, mis en place 2 manifestations en région centre

bretagne, dans

le nord ouest de la France, pour redonner vie à une abbaye cistercienne. Manifestations bi-annuelles, j’ai

ainsi crée

un symposium de sculptures semi-monumentales et une biennale d’art contemporain. Ces manifestations

perdurent ajourd’hui

et ont été reprises par des intervenants locaux dans le domaine de l’art contemporain.

Par ailleurs j’ai organisé en tant que commissaire free lance des expositions photographiques sur

Paris, notamment pour

des artistes suédois ainsi que l’ exposition inaugurale accompagnant l’ouverture de la Fondation

Jean Rustin,

artiste majeur de la peinture française, aujourd’hui âgé de 80 ans.

J’ai également crée et animé un blog artistique pendant près de 18 mois avec une historienne de l’art,

chacun

de nous écrivait en alternance un compte rendu d’expositions, de visites d’ateliers ou des textes

de fonds sur

un artiste, unee œuvre ou une période particulière de l’histoire de l’art.

Il y a deux ans, j’ai décidé de passer le pas et de me consacrer entièrement à ma passion artistique.

Il ne restait

plus qu’à trouver un lieu dans le quartier des galeries, au coeur du marais devenu l’épicentre

de l’art

contemporain à Paris, de lever des fonds et de constituer un team d’artistes et enfin de mettre en

place une programmation.

Isabelle Gounod:

Je pourrai évoquer l’héritage familial, composé de musiciens,

d’écrivains,

de peintres, d’acteurs, de poètes…et toutes ces années travaillant dans différents secteurs

de la production artistique,

le théâtre, la production de films et de documentaires, l’art-thérapie et les collaborations avec

des artistes, comédiens,

réalisateurs, photographes et plasticiens. Ils m’ont certainement conduite au fil des années à m’apercevoir

qu’il

m’était impossible d’envisager ma vie autrement qu’en adoptant cette « posture » qui est

celle de l’accompagnement

de l’artiste, de son œuvre. J’ai été comédienne et il me semble que ces années de travail

et de réflexion

sur l’écrtiture, le texte, les acteurs, le jeu de l’acteur, ont été essentielles et me permettent

peut-être une

certaine empathie avec l’artiste et sa démarche.

Loraine Baud:

C'est une décision qui s'est comme imposée à moi. J'ai toujours

travaillé auprès

d'artistes. En tant qu'agent, j'ai cherché la manière dont je pouvais porter leur travail. Et j'ai compris,

à la suite de

nombreux projets menés, que la structure de la galerie pourrait me permettre de mieux les soutenir et les

diffuser.

Comment décririez-vous votre galerie et les artistes que vous exhibez?

Olivier Castaing:

Spécialisée en art contemporain, la School Gallery représente

des artistes français

et étrangers, au travers d’une programmation interdisciplinaire,

Mon objectif, dans un premier temps, est de faire découvrir des artistes jeunes ou reconnus à l’étranger

mais sans réelle

visibilité en France, comme l’artiste argentine Marie ORENSANZ, figure incontournable de la scène

artistique sud américaine,

aujourd’hui âgée de 72 ans et à laquelle le Musée d’Art Moderne de Buenos Aires a consacré une

spectaculaire rétrospective

en 2007.

Cet intérêt pour la scène artistique argentine m’a incité à consacrer mes premières vacances depuis

l’ouverture

de la galerie à un long séjour à Buenos Aires où j’ai rencontré pas moins de 40 artistes, notamment

avec l’aide

d’Orly Benzacar directrice de la galerie du même nom et figure de proue des acteurs du monde de l’art

en Amérique

latine.

Je suis également animé par un réel désir de promotion d’artistes émergents pour rendre compte de

la diversité des pratiques

artistiques actuelles, soucieux de ne pas spécialiser la programmation sur tel ou tel média ou dans tel

ou tel domaine.

L’éclectisme me paraît primordial pour rester à l’affût de propositions originales et à même

de susciter l’intérêt

du public, des collectionneurs et des institutions et animer réellement un espace d’art et d’échanges.

La programmation s’oriente autour de 3 axes:

- des projets « engagés », comme le projet « water war » group show du printemps 2008 consacré aux « guerres

de l’eau

dans le monde », ou le livre et l’exposition « Testimony », projet photographique de l’artiste

suédois Joakim

Eneroth sur la torture des moines tibétains par les chinois …

Le choix de thématiques orientées sur les problèmes de société, illustre ma volonté de promouvoir des artistes

faisant montre

d’un « humanisme militant », avec des propositions qui entendent défendre les libertés fondamentales

comme l’

exposition inaugurale de la galerie intitulés « liberté toujours ! » (« ever free ») ou pour ouvrir la programmation

de deuxième

année l’exposition de l’artiste argentine Marie Orensanz « pour qui ? … les honneurs …

»,

- des expositions photographiques ou vidéos, près de la moitié des artistes de la galerie utilisant ces

médias dans leurs

créations, sans exclusive, certains étant également peintres, ou plasticiens au sens large.

- des projets plus prospectifs, incursions dans le domaine du design ou de l’architecture, installations

monumentales,

projets sonores, parcours artistiques.

Ce type d’exposition peut permettre d’intégrer des artistes qui ne sont pas sous contrat avec

la galerie mais

dont les propositions artistiques sont à même d’enrichir le projet.

Isabelle Gounod:

Je me sens incapable de décrire ce qui est en constante évolution.

L’on m’a

demandé quelle était la ligne directrice de la galerie… mes choix ! Il s’agit de rencontres

avant toute chose,

avec un artiste, une personne puis avec sa démarche, enfin ses/son œuvre(s). Chaque artiste est singulier,

je respecte

son exigence, une certaine intelligence du monde et l’ironie salvatrice et désespérée…

Je garde du théâtre cet esprit de troupe, de dialogue entre les « acteurs ». Si nous travaillons ensemble,

si nous nous «

choisissons », car c’est ainsi que cela se passe, c’est peut-être en partie par ce que nous

reconnaissons chez

l’autre, mais aussi pour nous laisser guider par eux …

Loraine Baud:

Une galerie est à la fois espace d'exposition et plateforme de

médiation. Je la

pense comme un lieu ouvert, un espace d'échange. Ce qui induit une posture, tant vis-à-vis des artistes

avec qui je travaille

en étroite collaboration, que de l'accueil des visiteurs. Avec audace et humilité, j'ai l'ambition de proposer

un regard neuf,

de défendre une peinture contemporaine, de promouvoir un art incarné.

Comment avez vous trouvé les artistes que vous représentez?

Olivier Castaing:

J’ai démarré ma programmation en 2008 avec des artistes

que je connaissais

déjà, soit pour les avoir intégréé à mon projet de biennale, soit pour leur avoir consacré une exposition

personnelle au travers

de mon activité de commissaire d’exposition free lance dans les années antérieures.

C’est le cas de Naji Kamouche, qui a participé à la première Biennale d’art contemporain de

l’Abbaye de

Bon Repos (Bretagne/France) Joakim Eneroth rencontré à FOTOFEST (Houston Texas) ou Susanna Hesselberg ,

soutenue lors de sa

résidence d’artiste à la Cité internationale des arts à Paris.

Aujourd’hui les nouveaux artistes sont surtout cooptés par ceux qui font déjà partie du team de la

galerie mais aussi

recommandés par des commissaires d’exposition ou des historiens de l’art avec lesquels je collabore.

Pour moi, choisir une galerie c’est comme entrer dans une famille, et l’avis de tous les membres

est important,

même s’il n’est que consultatif, il oriente de façon significative mes choix finaux.

Isabelle Gounod:

J’ai vécu avec un photographe plasticien et rencontré à

cette époque des

artistes qui sont devenus des amis, dont certains avec lesquels je travaille aujourd’hui, ainsi

Michaële-Andréa Schatt que je connaissais depuis 1991 bien avant de décider d’ouvrir une galerie.

Je souhaitais réaliser

un documentaire sur son travail, cela ne s’est pas fait mais des années plus tard je lui ai demandé

si elle accepterait

de rejoindre une galerie « débutante », située dans une petite rue de la banlieue de Paris et nous avons

inauguré la galerie

ensemble. C’était une petite galerie, un peu « la petite boutique au coin de la rue » ! J’avais

rencontré également

Michel Alexis qui vit et travaille à New-York et à Paris qui nous a également rejoint et présenté une série

de peintures «

autour » du Journal de Gertrude Stein… Un soir d’hiver 2004, je reçois un mail de Jérémy Liron,

un jeune étudiant

aux Beaux-Arts de Paris. Je découvre sa peinture, ses écrits… il « débutait », moi aussi… !

Je suis très souvent

sollicitée par les artistes depuis que la galerie est à Paris… c’est pourquoi je suis d’autant

plus reconnaissante

à ceux qui m’ont fait confiance depuis le début.

Le petite « troupe » s’est élargie, accueillant d’autres « acteurs », mais il s’agit toujours

de rencontre,

du désir de se rencontrer. C’est un élément moteur, stimulant et infiniment subtile.

Loraine Baud:

Ce sont les artistes avec qui je travaillais déjà qui m'ont donné

l'envie et le

courage de monter la galerie. Ce sont eux qui m'ont insufflé le désir de présenter leurs oeuvres, de les

accompagner.

Quel est votre plus grand défi avec la galerie?

Olivier Castaing:

La question est de savoir comment exister au milieu des 500 galleries

voir plus

qui sont présentes sur le marché de l’art parisien.

Comment sortir du lot, se forger une personnalité identifiable et être à même d’obtenir une raisonnance

suffisante dans

la presse, auprès des institutions et des collectionneurs sur votre programmation et les artistes que vous

promouvaient.

Il s’agit en premier lieu d’exister et ensuite de s’inscrire dans la durée.

C’est à la fois un challenge économique, compte tenu du prix prohibitif des loyers, des coûts de production

et des risques

inhérents au marché.

J’ai axé ma différenciation sur la qualité de l’accueil, la présence la plus fréquente possible

des artistes,

pour les remettre au coeur du système, considérant qu’ils sont trop souvent les « grands absents »

des galeries, et

que cela devient presque un challenge que de rencontrer un artiste dans sa propre exposition. Enfin pour

créer l’événement,

chaque exposition est prétexte à organiser des rencontres, afin d’être une plateforme d’échanges

permanents et

de rencontres avec les artistes associés à des personnalités d’horizons différents : écrivains, psychiatres

et psychanalystes,

architectes, paysagistes, enseignants et chercheurs, politiciens, afin de générer une réelle dynamique et

des débats stimulants

avec les collectionneurs et amateurs d’art, et le public en général.

Isabelle Gounod:

Durer!

Loraine Baud:

La faire exister sur la scène internationale.

Quel est votre plus grand défi avec vos artistes?

Olivier Castaing:

Comme toute galerie le soutien aux artistes concerne la production

des pièces présentées,

l’assistance sur des projets hors les murs, des publications notamment en faisant systématiquement

appel à des historiens

ou critique d’art pour qu’ils écrivent sur chaque projet d’exposition afin de contextualiser

le travail.

Accompagner des artistes dans le temps, doit être l’objectif qui conduit toute l’activité de

la galerie. Il s’agit

avant tout de focaliser l’énergie sur toutes les opérations à même de montrer, valoriser le travail

de l’artistes

au sein de la galerie mais aussi et surtout dans les institutions et collections publiques ou privées.

C’est un travail en binôme, qui suppose une confiance absolue, une osmose véritable pour être le mieux

à même de défendre,

soutenir, faire sortir dans les meilleurs conditions le travail de l’atelier.

Pour un jeune galeriste, cela passe par la constitution d’un réseau de collectionneurs actifs, qui

croient dans les

choix de la galerie, susceptibles de s’engager sur certains projets lourds, notamment en production,

la mise en place

d’un réseau de correspondants institutionnels, de journalistes prêt à suivre le travail des artistes

et du galeriste.

C’est un véritable marathon au quotidien, une course de fonds qui nécessite enthousiasme, énergie

et plus que tout la

passion des artistes et de leur art.

Isabelle Gounod:

Les rassurer… Galeristes, commissaires, conservateurs,

critiques, nous sommes

tous des « passeurs » - nous puisons notre énergie dans la relation que nous avons à l’art grâce aux

artistes. Le défi

? Pas de défi avec les artistes si ce n’est celui de les accompagner dans le temps, de leur donner

la parole.

Loraine Baud:

Leur donner la possibilité de produire le plus librement possible,

et poursuivre

notre collaboration le plus longtemps possible, dans le même climat de respect, de transparence et de confiance.

|

| From left: School Gallery, Galerie Isabelle Gounod, Galerie Loraine Baud. |

|

|

|