|

|

|

| Lilburn, Georgia, USA. Photo: Mike Jensen, 2008. |

Introduction

by Deanna Sirlin

Editor-in-Chief

The Art Section

The October Art Section is finally here. And The Art Section is evolving. You may have noticed that we have

launched on the 15th of the month; our plan is to continue to do so (although the issue after our November/December issue

will appear on January 15th, 2009). You will also be seeing more articles by yours truly. I have begun a series on Women and

the Art World with a recollection and appreciation of the artwork of Anne Truitt.

And something very new: I commissioned the artist and photographer Mike Jensen to photograph the BAPS Shri Swaminarayan

Temple, a new Hindu sanctuary in Lilburn, Georgia. Lilburn, which is part of Atlanta’s sprawling suburbia, is changing

dramatically. As Kathy Lohr reported for

NPR, "The temple is an engineering marvel. No steel or metals have been used in the construction, and each piece, hand-carved

and imported from India, was numbered, divided into sections and eventually set in place. The whole structure fits together

like a giant jigsaw puzzle."

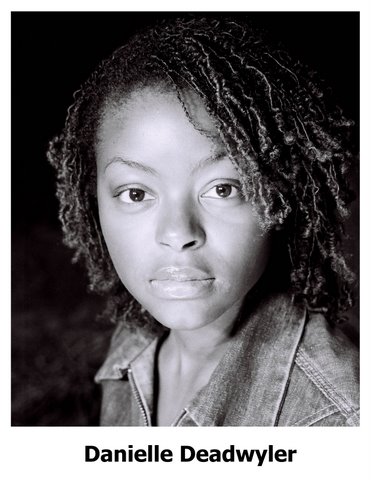

I was so delighted by Mike Jensen’s photographs that I showed them to poet Danielle Deadwyler, who was inspired to write

a poem for this issue. Mike Jensen has generously agreed to make this portfolio available as a limited edition and to donate

part of the proceeds to benefit The Art Section. If you would like more information please click here. I hope this will be the first of many TAS inspired artist’s projects.

And last, but certainly not least, Phil Auslander recently gave a lecture at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center (aka The

Contemporary) on Brian De Palma’s The Phantom of the Paradise, which has now become a cult film. His article

is adapted from that presentation.

All my best,

Deanna

|

| Photo: T. W. Meyer. |

www.deannasirlin.com

|

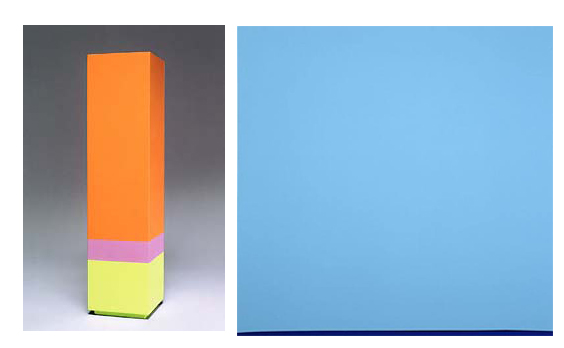

| From Left: Anne Truitt, Parva XXIX (1993) and Blythe (1998). |

Not So Carefree

Anne Truitt: An Appreciation

by Deanna Sirlin

I have been thinking a lot about Anne Truitt this year. She is an artist for whom I have the utmost admiration, and I have

thought of her often since her death in 2004. We met at the artists’ colony Yaddo in the summer of 1983, which seems

like a million years ago. I was at the beginning of my life as an artist—a young pup of a painter—while she was

at a mature state of her artistic life, generous with her thoughts and ideas and friendship.

At the time I met Anne I knew very few woman artists of her generation. I neither knew her work nor had heard of her books.

The fact that I thought Minimalism was just a movement from the early 70s was not a great reflection on my education, but

every school has its biases.

But I did understand her paintings, sculptures, and drawings. They were so like her: clean and clear, and yet so personal

in their touch. You felt the presence of her stroke even in works where you saw no stroke. The colors were rich and flat,

yet luminous and bright.

I remember Anne in her starched oxford shirts, big glasses, and bowl-shaped white hair. She must have been about 62 when we

met. What a contrast with me at 24, in my floral pattern shirts, brightly colored in colors like magenta and teal, often with

paint stained body parts that were as bright as my clothes. The contrast between us was dramatic, but the language of painting

transcends superficial values like clothing and age.

Not to say that age makes no difference at all. I remember reading Anne’s book Turn sometime in 1986 after the

book was published. Later that year I saw Anne at the Phillips Collection in Washington where we met in the Bonnard room,

more to my taste than hers, perhaps, and we talked bout her book. When I told her I found Turn depressing, Anne reassured

me that if I were to reread the book in 20 years, I would find in it comfort rather than sadness. I did reread Turn

more than 20 years later and discovered, of course, that she was correct. I found her description of the effort of going up

and down a ladder to paint coat upon coat of color on her sculptures, even through pain and exhaustion, exhilarating. Was

I hearing her voice or my own? Her voice reaffirmed my belief in the process of making art. Artists face obstacles throughout

their lives: the young artist’s angst gives way to the physical trials of the mature artist. But reading Anne’s

writing made me realize that although making art does not become easier as one gets older, the process remains energizing.

This past summer, Anne’s work was part of a group exhibition titled Painting: Now and Forever, Part II at Matthew

Marks Gallery in NYC, which opened on the tenth anniversary of Painting: Now and Forever Part I which showed originally

at both the Mathew Marks and Pat Hearn Galleries.

One of Anne’s works included in this exhibition was her acrylic painting Blythe (1998), a lovely sky blue, sleekly

painted square with a small curvilinear dark blue shape that stretches across the bottom. I have to admit that the title confuses

me. The spelling Anne used is usually used as a woman’s first name, though the evocation of “blithe,” which

can mean carefree or casually indifferent, makes me wonder to whom or what she was referring. Was she being ironic, or just

naming something the way it felt to her, something personal or perhaps even autobiographical in nature?

Other works by Truitt in the exhibition were brightly and lovingly painted monoliths, strong and straight and bold, so like

the artist herself. Although painted sculpture, or three-dimensional painting, has always been a bit hard to pigeonhole,

this form is the perfect articulation of her aesthetic. Rectilinear columns with intense color wrapped around them became

the hallmark of her work.

It is interesting to compare the hand of Mary Heilmann, the only lucky artist who got to be in both editions of Painting:

Now and Forever, with Truitt’s. Mary‘s stroke is of the thick, clean, liquid, you-do-it-once-so-you’d

better-get-it-right variety, while Anne’s reflects the Puritan ethic of layering and layering until it is right, or

starting over from scratch.

So was Anne gently mocking her own earnestness with her title? Was the mother of Minimalism so carefree? Was she trying to

escape the tireless worker bee, who works the painting until it seems effortless, in herself? Or does any of that process

stuff matter anyway--isn’t it form that leads us to the content of Blythe ?

When I climb the ladder in my studio to reach the top of a painting, or get on my hands and knees in the course of working,

I delight in having known one whose work and voice inspire me to go on.

Thank you, Anne.

The first major exhibition of Truitt’s work since 1974, Anne Truitt: Perception and

Reflection, a survey of two- and three-dimensional works made during the artist’s 40-year career, will open at the

Hirschhorn Museum on October 8, 2009. “Truitt has been largely under-recognized for her contribution to post-1960 art.

The exhibition is organized by associate curator Kristen Hileman and will be accompanied by the first complete monograph on

the artist.”

|

| Photo: T. W. Meyer. |

Deanna Sirlin is Editor-in-Chief of The Art Section and an artist whose work can

be seen at www.deannasirlin.com.

A Photo Essay

by Mike Jensen

The Art Section commissioned a portfolio of images of the magnificent Hindu temple in Lilburn, Georgia,

from photographer Mike Jensen. Please click on the thumbnails below to see larger images. If you would like to help support

The Art Section by purchasing any of these images or the entire portfolio, please click here.

Mike Jensen is a photographer who lives and works in Atlanta, Georgia.

Candied Beauty

by Danielle Deadwyler

God, too, delights in play--

In sniffing petals coloured as deep beyond the skin;

In carousing the heroine’s landscape

For puzzle pieces, grass beds, and open doors;

For sandcastles, frosted ornamentation,

And dollhouses only tinkered with in imagination, and memory.

Anything, that considers creation,

Through the final scrapings by white nails

Or smoothened between palm

Lifelines and weariness, continents, ouerves;

Praise for such sweets.

Danielle Deadwyler is a community educator and multidisciplinary performance artist/writer who lives and plays in

Atlanta, GA.

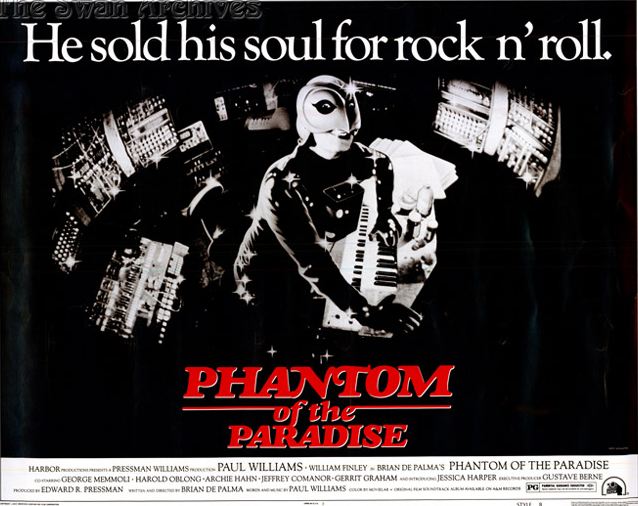

A Look Back at Brian De Palma's

The Phantom of the Paradise

by

Philip Auslander

In Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music (University of Michigan Press, 2006), I argue that

glam was the first full-fledged genre of rock music of the 1970s. Around the turn of the decade, performers like Marc Bolan

(of T. Rex) and David Bowie sensed the exhaustion of the hippie counterculture and the need to develop new forms of expression

for the new decade. Glam rock was thus a product of a transitional cultural moment; as such, it was fraught with ambivalence.

Its practitioners wanted to distinguish themselves sharply from their predecessors, but without rejecting everything for which

the counterculture had stood.

The same ambivalence is visible in other cultural artifacts of the period, including Brian De Palma’s film The Phantom

of the Paradise (1974). It is a glam film, in the sense that it is campy, artificial, self-conscious, theatrical, excessive,

way over the top. DePalma’s rather baroque style as a director goes well with the glam sensibility. The Phantom also

blends genres, something I consider to be characteristic of glam rock: it is at once a horror film, a parody of horror films,

a social satire, and a movie musical. The film acutely reflects the sense within rock culture that the 60s were over. But

whereas a film such as The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) celebrates the glam sensibility as liberatory, De Palma

treats glam rock as just another product purveyed by an essentially corrupt music industry that has sold out whatever idealism

rock music may have reflected in the 1960s.

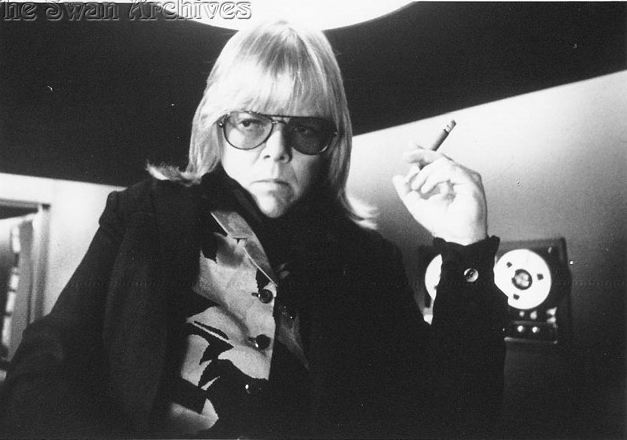

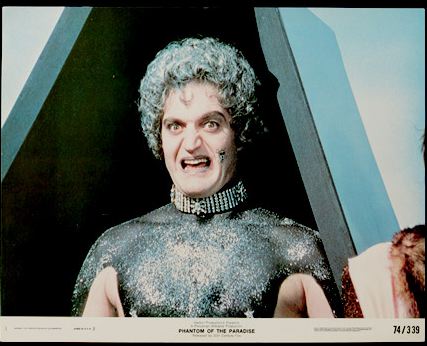

|

| Paul Williams as Swan. |

The plot of The Phantom of the Paradise draws liberally from the Faust legend,

The Phantom of the Opera, and The Picture of Dorian Gray. It contains visual allusions to Psycho and

The Hunchback of Notre Dame, as well as German Expressionism and Frankenstein. There are three principal characters:

Swan (played by songwriter and actor Paul Williams), the evil record producer and owner of Death Records, who steals the composer

Winslow Leach’s music, has him imprisoned, and tries to kill him; the na´ve Leach (played by William Finley) who, as

a consequence of a series of incidents engineered by Swan ends up disfigured and incapable of speech, let along song, and

becomes the phantom who haunts the Paradise, Swan’s newly opened rock palace (the movie’s working title was The

Phantom of the Fillmore); and Phoenix (played by Jessica Harper), the lovely girl singer for whom Leach writes music and

who is eventually co-opted and corrupted by Swan. Once Leach has become the Phantom, by stealing a bird-like costume from

Swan’s wardrobe department, Swan dupes him into signing away his soul in exchange for the chance to compose for Phoenix.

Later, it is revealed that Swan had earlier signed a similar contract with the Devil himself, exchanging his soul for eternal

youth. As part of this bargain, a videotaped image of himself ages in his place.

Because Swan and the Phantom (and, eventually, Phoenix) are bound by the same contractual terms, their fates are interlocked

and the Phantom cannot die until Swan does. (The bird imagery in the film suggests their entwinement: Swan and Phoenix are

named for birds; Winslow Leach makes it an avian troika by taking on the image of a bird as the Phantom and ultimately kills

Swan by stabbing him with a bird mask that somewhat resembles the one he wears.) Indeed, the symbiotic relationship that develops

between the two men—one representing art, the other commerce—is at the heart of the film. As Swan loses control

over his own destiny and starts to age, he, too, appears as a masked figure. In the final, climactic scene of the film, which

takes place during a performance that is supposed to double as a presentation of Leach’s opera and a marriage ceremony

between Swan and Phoenix, both are unmasked, their disfigurations revealed, and lose their lives.

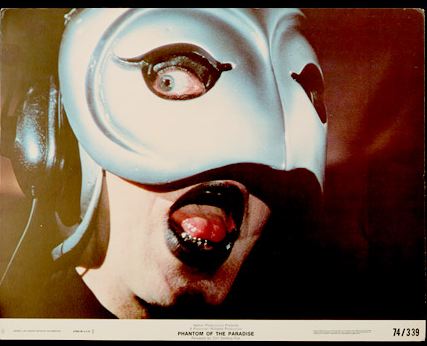

|

| William Finley as The Phantom. |

There is more than a whiff of post-1960s (that is, post counter-cultural) disillusionment

in The Phantom of the Paradise. The idea that Swan wants to open a rock palace along the lines of the Fillmores East

(in San Francisco) and West (in New York City) is anomalous for 1974, given that both Fillmores closed in 1971. There is,

however, no 60s-style idealism in Swan’s desire to revitalize this kind of venue—no sense that art and commerce

could hold hands to bring about a better world. The development of the Paradise is a purely cynical, commercial move by a

clearly corporate, corrupt, and violent music entrepreneur who profits from the talents of his artists and capitalizes on

the gullibility of his audiences. Swan’s body guards are dressed as bikers, perhaps in a reference to the Rolling Stones’

having used Hells Angels for “security” for their concert at Altamont late in 1969, an event often cited as the

moment at which the counterculture died. The fact that the three of Swan’s groups that we see in the film—the

50s revival act the Juicy Fruits, the Beach Bums, a truly dreadful surf group, and the goth/glam group the Undead—are

all played by the same three actors humorously underlines Swan’s cynicism: it’s always the same thing, just packaged

differently.

One does not have to agree with De Palma that rock sold out in the 1970s (though

there are many who do) to agree that the 1970s nevertheless saw the exhaustion of the rock counterculture. In the film, one

sign of rock’s exhaustion is that Swan’s main act, the Juicy Fruits, is a 50s doo wop revival act; the reference

here is clearly to Sha Na Na. In the absence of anything new, the music industry simply recycles the familiar (and whereas

Sha Na Na’s appearance at Woodstock in 1969 had been a provocative harbinger of rock’s turn toward overt spectacle,

by 1977 the group would become the defanged house band for a syndicated television variety show). Swan recognizes glam rock

as the new sound he seeks but, as represented by Beef (played by Gerrit Graham), the performer Swan hires to sing Leach’s

music, who is a prissy, klutzy, coke-snorting mama’s boy of questionable talent, glam is just the latest swindle perpetrated

on the public by Swan.

|

| Gerrit Graham as Beef. |

There is, however, a crucial false note in De Palma’s treatment of popular

music in the film, in a sequence in which the Phantom assassinates Beef because he wants only Phoenix to perform his music.

The gambit succeeds, as Beef’s death gives Phoenix the opportunity to step forward and become a star. The song she performs

is a Carpenters-like ballad quite different in sound from the raucous treatment to which Beef subjected Leach’s music.

As Pauline Kael astutely observes in her review of the film for the New Yorker (November 11, 1974) De Palma’s

misstep here is in treating this scene unironically. As a result, the film seems to valorize very middle of the road pop over

all other genres of popular music as somehow real, authentic, truly emotive, untainted, not just another fraud perpetrated

by the Swans of this world (at least, this is what the hushed response of the audience in the film implies). The resemblance

to the Carpenters is not at all coincidental, since Paul Williams, who wrote all the songs in the film, also wrote some of

the Carpenters’ biggest hits. I don’t mean to take anything away from Williams, from Jessica Harper (who is a

fine singer) or from the Carpenters when I say that to hold up this kind of music as the real thing is not a very satisfying

rejoinder to De Palma’s implicit critique of the state of rock in the 1970s. As Kael suggests, it would have been more

consistent for De Palma to use this scene to show that Phoenix, like everyone else in the film, despite her apparent innocence,

stands to be corrupted by her lust for audience and fame.

De Palma casts a critical eye not only on those who make music but also on their audiences. The two major performance scenes

in the film both show orgiastic rock audiences so caught up in the moment that they are completely unaware of the death and

mayhem actually taking place in their midst. In the glam rock performance scene, which alludes to both German expressionism

and Frankenstein, and expropriates Alice Cooper’s appropriation of horror film imagery, Beef is murdered by the

Phantom while on stage, to the audience’s delight. The point of the scene, clearly, is that whereas the performers understand

what’s going on, the audience does not, and only becomes more and more excited as people are killed and fire breaks

out.

|

| Jessica Harper as Phoenix. |

The film’s orgiastic final scene reprises this theme especially chillingly. At Swan’s televised marriage to Phoenix,

during which she is to be killed by a hit man he hired in the belief that her death will increase her record sales, the dancing,

freaked-out crowd has no idea of what is actually unfolding in their midst. The audience cheers as one man is shot and takes

a dying man crowd surfing, while a character identified in the credits as the Rock Freak imitates Winslow Leach’s death

throes, displaying no sense that he has any idea of the implications of the movements and gestures he duplicates. This character

was played by William Shepard, who is also credited with choreographing the scene. Both Shepard and William Finley, who played

the Phantom, had been in the well-known experimental theatre production Dionysus in 69, of which De Palma had made

a documentary film. (Another relevant branch in The Phantom’s theatrical genealogy is that Jessica Harper had

been an understudy for the Broadway production of Hair.) Dionysus in 69, in keeping with the ethos of the 1960s,

made much of breaking down the barriers between audience and performers; here, the sundering of that boundary has ominous

implications. The audience is so caught up in the rush of spectacle and activity that it is completely oblivious to the human

toll being taken and its own complicity.

Finally, the film’s grim ending underlines another motif in the film: death as a profitable undertaking. This unpleasant

thought is perfectly understandable in the context of the early 1970s, when recently deceased rock stars like Jimi Hendrix

and Jim Morrison were as important as living ones and enjoyed lucrative posthumous careers that continue to the present day.

But there’s a curious inflection of this theme in the film, which opens with the Juicy Fruits singing a song called

“Goodbye, Eddie, Goodbye.”

The song, a pastiche of the morbid “Last Kiss” genre of rock tunes of the late 1950s and early 1960s, tells of

a rock ‘n’ roll star who kills himself “for love,” knowing that his death will force his newest record

to the top of the charts and make lots of money, so his sister can have a needed operation. It is implied that, at one time,

it may have been possible to see rockers as sacrificial figures giving themselves over to a greater good. For Swan, however,

it’s all simply about the bottom line. He sees the death of Beef as good marketing and decides to kill Phoenix for a

similar benefit. De Palma seems to be saying that any selflessness and self-sacrifice there may once have been in rock performers’

giving of themselves, which was, in any case, always tainted by the need for an audience, is definitively corrupted, like

the music itself, like the audience, by the desire for sensation and profit—despite occasional protestations to the

contrary, no one in The Phantom of the Paradise does anything for love.

The author would like to thank Stuart Horodner and the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center for inviting

me to speak and the Swan Archives for images and information. Please visit this site for more on The Phantom of the Paradise.

Philip Auslander writes on art, music, performance, and culture.

www.philipauslander.com

|

|

|