|

|

|

| Tatsuo Miyajima, ENGI, 2006. Denver Art Museum. Photo: George Hornbein. |

|

| Roy Lichtenstein, The Violin, 1976. Denver Art Museum. Photo: George Hornbein. |

I’d heard that the roof leaks on Daniel Libeskind’s new Fredrick

C. Hamilton addition to the Denver Art Museum. But that wasn’t my main concern when I visited; they can fix the leak.

I had seen some marvelous photographs of Liebeskind’s dramatic forms and I was hoping that the building would not disappoint

when I actually got to see it. Would its scale work on the site? Would the soaring forms carry through from the exterior

to the inside? Would the gallery spaces end up being broken into a labyrinth of boxes? Or worse, would the forms fight with

the art and dominate it (as unfortunately occurs so often in contemporary museum design)?

The ticket windows are at the base of a glass stairway that frames the building’s entrance, thus allowing museum

patrons to take care of business before the museum experience begins. The little plaza before the museum is bounded by the

museum’s slanted titanium planes, the Michael Graves’ library, Libeskind’s Museum Residence condo, the thirty-five

year-old Gio Ponti museum building, and the walkway to the city. The scale is human, the feel is light, and with the postmodern

Graves building, the plaza lacks the gravity one traditionally expects from a public complex displaying instead a sense of

humor that speaks well of Denver’s sense of itself as city.

As you cross the plaza, the museum’s titanium wall plates soar over you and glow from direct and reflected sunlight

and you are drawn to touch them to see if they feel as soft as they look. The tilted wall planes and the steel skeletal structure

expressed on the exterior are carried through to the interior where the structure is wrapped in gypsum board rather than titanium.

The distinction between walls and ceiling planes is not always clear and you find yourself walking through arrays of folded

planes.

As you first walk into the atrium it seem overly dark. But as your eyes adapt you realize that the window slits admit

natural light in measured amounts that do not dominate the artificial light, producing a play of cool natural light with warm

artificial light. Six-inch wide mirrored disks with randomly changing blue LED numbers further accent this play of color.

The disks, which were conceived by Tatsuo Miyajima, are randomly set in the wall planes and help to define the walls.

The main stairway follows the bent wall planes to the upstairs galleries. The rooms are irregular, but here there is

a traditional ceiling plane. In the large galleries, movable partition walls break up the interior space and form the display

surfaces. The partition walls are about a foot thick and are quite substantial, while still giving the curator flexibility

in arranging variable gallery layouts. The height of the partitions is a few feet short of the ceilings, enough so that the

flow of space in the gallery room itself is not interrupted. In smaller galleries, the walls are sometimes tilted, making

the display surface unconventional. I spoke with a few patrons who found that the sloped walls made them feel a little queasy.

There is no doubt that the museum’s angular forms and unconventional slits of natural light affect the displays

of art. But rather than fighting the art for dominance, the environment enhanced the artwork and could accentuate the abstract

forms of the pieces. There is, for example, a Roy Lichtenstein painting whose angular forms play with the lines of the building

in a way that would never happen in a conventional gallery space, inviting you to extend the lines of the painting until the

building forms pick them up and carry the lines outside the painting’s frame. On an adjacent outdoor terrace, there

was what I took to be a series of stainless steel fresh air vents. I walked around to the other side expecting to find an

array of louvers that, instead, turned out to be an array of cubes forming a Donald Judd sculpture.

This museum is an exciting place, which, for me, was never disappointing. The forms are charged with energy. The detailing

is beautifully and logically carried out. And the art is displayed in a way that allows the building forms and sculptured

light to enhance the work.

George Hornbein

Atlanta, May 2007

|

|

|

|

|

George Hornbein is an architect and principle in the firm of HOKO Architects in

Atlanta

The Contemporaneity of Music

by Giuseppe Gavazza

Translated from the Italian by the author

|

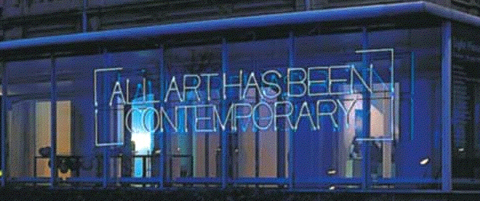

| Maurizio Nannucci, All Art Has Been Contemporary, 1999. |

Could a non-contemporary mother exist?

Can we equate artistic creation with a pregnancy?

In such a case the newborn - created in a relatively short period - will grow up to become a fully independent being. Years

later, mo/fa-ther will die and she/he/it (probably) will survive as an independent (maybe long-lived) individual with its

own first + family name.

Art repertoire is a Someoneson, like a big ancient nation: it is through these art works that the fa-ther/mily name also survives.

Goldberg-Variationen, La Divina Commedia, Les Fleurs du Mal, la Cappella Sistina, Hamlet, Mona Lisa, Der Process all still

exist. And through them the mother/artist generator still lives.

I remember seeing on the entrance to Turin GAM (Modern Art Gallery) a big neon sign (I think it was - it is - a work of Maurizio

Nannucci) saying, in English, “All art has been contemporary.”

Non-contemporary art exists: it is art history.

But could a non-contemporary artist exist?

It is very difficult (quite impossible) to escape contemporaneity, especially for a musician, for several reasons:

1 - Sound is contemporary: its life is momentary. Sound exists only for real-time perception.

2 - Music (as organized sound) lives on in the memory of human listener.

3 – Memory exists because human beings are alive; each has his own history (life) as a background.

In1 and 2, I refer to sound and to music: music is made of/with sounds, we all know this simple truth. But most of the inventory

of existing music isn’t made of sounds; it consists of written pages. Music history is the history of musical writings

(scores); but musical writing was invented just to synchronize sounds.

Because the perception of sound (audition) is not strictly directional (it’s a very astigmatic sound-vision) we have

a compelling polyphonic perception.

When composers have wanted to be the primary performers of their own music, polyphonic keyboard instruments - like organ and

piano - have reigned as the kings of instruments, and many composers were indeed good keyboard players. But to develop a full

and complex polyphonic sound they always needed many instruments or voices playing at the same time, and until the arrival

of multi-track recording technology, the only way to realize such a goal was by writing a score.

This could be the reason that although we know music is made of sounds we disregard the fact that a musical composition is

nothing more then a long, complex, well articulated single sound; it is a unique object like a painting, a sculpture or a

building. Musical writing imposes a lexical vision (audition) of music but more and more, the listener’s consciousness

realizes that form has meaning only because it resonates in our internal perception, connected with memory.

Or not?

Giuseppe Gavazza

May 17th 2007

www.giuseppegavazza.it

Giuseppe Gavazza is a composer who lives and works in Turin, Italy.

The Artist’s Presentation of Self:

Annie Leibovitz at the High Museum

by Philip Auslander

|

| Annie Leibovitz at the High Museum, in front of her photograph Monument Valley, Arizona, 1993 |

I have long been interested in the practice of asking visual artists to speak about their work, as museums, universities,

and other institutions so often do. While I don’t see anything wrong with wanting artists to articulate what they do,

I also find myself wondering whether, in the end, we believe that the work speaks for itself. If so, why do we want the artist

to speak for it as well?

Hearing an artist speak is not just about the ideas and whatever light they may shed on the work, however; it is also about

having an encounter with the artist as a person, perhaps as a celebrity. And the persona the artist presents on such an occasion

must somehow meet the needs of the audience, whether for information about the art and the process that led to it or for an

opportunity to rub shoulders with a famous person.

During the press conference held in conjunction with the arrival of Annie Leibovitz’s exhibition A Photographer’s

Life: 1990-2005 at the High Museum in Atlanta, on May 11, 2007, Leibovitz addressed this task with skill and aplomb. While

many in her audience wanted to treat her as a celebrity, she consistently downplayed her own fame and that of her photographic

subjects, emphasizing instead the common humanity of all.

As Leibovitz walked through the show discussing selected images and their backgrounds, intriguing fault lines appeared in

her self-presentation. At one moment, she described herself as “an artist who uses photography” rather than a

photographer while insisting, at other moments, on her identity as a working photographer much of whose work is commissioned

by magazine editors. She distanced herself from journalism, however, arguing that her work reflects a point of view rather

than a journalist’s objectivity. Nevertheless, standing in front of a formal portrait of President George W. Bush and

his cabinet, she suggested that the photograph was staged and composed in such a way that those who agree with Bush would

see it as admiring, while those who disagree would see it as critical.

The conceit of the exhibition is, in the museum’s words, to bring together “images Leibovitz created on assignment

as a professional photographer [with] personal photographs of her family and close friends.” Many of the personal images

are of Susan Sontag, to whom Leibovitz was close for the 14 years prior to Sontag’s death; they provide a glimpse of

both their private life together and Sontag’s decline. Despite the intimacy of these pictures, Leibovitz referred consistently

to “Susan” without ever specifying the nature of their relationship.

It should be clear that in pointing out Leibovitz’s inconsistencies and reticence I seek neither to criticize nor psychoanalyze

her. Rather, they constitute the details of the performance of an artistic identity that reflects the ambiguities inherent

in Leibovitz’s position as a photographer with one foot in the world of magazines and the other in the art world. Is

such a person to be understood as a graphic artist or a fine artist? As she moves back and forth between those roles, what

is the relationship between the two bodies of work produced? Perhaps the role of artist requires the communication of a point

of view that the role of journalist precludes. But photography, as opposed to painting, has long been seen as somehow inherently

objective—the image, after all, is recorded by a machine rather than by a human being (it was for this reason that photographs

were originally excluded from copyright). As Sontag puts it in On Photography, photographs enjoy a “presumption

of veracity”: “there is always a presumption that something exists, or did exist, which is like what’s in

the picture.” As some photography has come to be considered fine art, it has not completely lost this connotation, even

though its mechanical, utilitarian, and journalistic associations undermine its status as art, a tension indicated in Leibovitz’s

competing self-descriptions as both a lens for hire and an “artist who uses photography.”

The distinction between “personal” and “on assignment” is similarly fraught with tension. The idea

of the “professional photographer” working on assignment evokes an image of the photographer as functionary, executing

someone else’s ideas. This leaves the personal as the realm in which the photographer can act as an artist to convey

her own vision. Leibovitz’s comments reflect the difficulty of maintaining such a distinction. She wants us to see the

work she does on assignment not as journalistic but as reflective of her own point of view, even as the realities of what

it means to take photographs of public figures for mainstream publications haunt the margins of her comments on the photograph

of President Bush. In one sense, Leibovitz’s reticence with respect to Sontag made those images seem particularly intimate,

as if what’s represented in them is too personal even to be spoken. But since that reticence also cuts her audience

off from her point of view, it may contribute to an impression that these images are those of the photographer showing us

what was there, rather than the artist showing us what she felt.

Meeting the press, Leibovitz seemed open, affable, accessible. She spoke well and enthusiastically about her work and her

roles as photographer and artist. Her presentation of artistic identity was not seamless, however, and as the seams became

visible, they suggested a fascinating subtext concerning the inherent tensions between photographer and artist, objectivity

and subjectivity, personal and professional, public and private.

Philip Auslander

Atlanta, May 2007

http://lcc.gatech.edu/~auslander

Philip Auslander teaches Performance Studies at Georgia Tech.

|

|

|